Many incidents during the American colonial period combined to convince colonists to rebel against the British Crown. The 1770 Boston Massacre was one of the most significant of those incidents because armed British troops fired into an unarmed but hostile and physically confrontational crowd killing five. The American crowd could only be described as a “mob.” They were throwing objects at the soldiers and taunting them with shouts of “fire.” The killing began when one angry and nervous soldier fired without orders and the others reacted by firing into the crowd. News of the Boston Massacre traveled fast and was used to stir up anti-British sentiment for years.

Boston was the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was the major seaport of New England. The city was large and prosperous. It was also the center of resistance to acts by the British Parliament that the colonists believed were unfair and violated American’s rights as British citizens.

Most of Parliament’s acts involved additional taxes. The British were trying to recover the costs of their many wars, including the costly and bloody 1756-1763 French and Indian War (Seven Year’s War in Europe.) They also needed to finance the British troops stationed in America as a security force. The colonists believed they were not responsible to pay taxes that they did not enact and had no sympathy for the British taxes since Britain’s trade with America was quite profitable.

In 1767 and 1768 Parliament passed the Townshend Acts which imposed duties on British china, glass, paint, and tea being imported to the colonies. These items were selected because it was believed they would be difficult for the colonies to produce. Benjamin Franklin had told the British that the colonies would produce their own goods rather than pay the taxes.

The Massachusetts House of Representatives sent a petition to King George III asking for the Townshend Acts to be repealed. They also sent the Massachusetts Circular Letter to the other colonies asking them to join the resistance and calling for a boycott of British goods.

The petition was rejected and Lord Hillsborough, who had recently been appointed to the new office of Colonial Secretary, was alarmed by the Massachusetts actions. He sent a letter to the American colonial governors ordering them to dissolve any colonial assemblies that responded to the Circular Letter. He also ordered the Massachusetts Governor to direct the House to rescind their letter. The House refused to comply.

Adding to the building tension, Boston’s customs officer asked Hillsborough for more military support because he claimed the situation was much like it had been at the time of the 1765 Stamp Act. In response, the 50-gun HMS Romney sailed into Boston Harbor in May 1768. In June British customs seized the Liberty, a sloop owned by leading and popular merchant John Hancock claiming it was involved in smuggling. The citizens of Boston were already upset because the Romney captain was impressing American sailors, and they rioted. The customs officials had to flee to Fort William on Castle Island for protection.

In response to the escalating situation, Hillsborough ordered General Thomas Gage to deploy forces “you think necessary” to Boston. Four British Army regiments were deployed in October 1768. Two of those regiments were removed in 1769, but the 14th and 29th Regiments of Foot remained. Each regiment had a roster of about 650 men.

A series of newspaper articles that were mostly exaggerated accounts of clashes between civilians and soldiers contributed to rising tensions. The incident that nearly pushed tensions to the breaking point involved eleven-year-old Christopher Seider who was killed by a customs employee on 22 February 1770. His death and funeral were covered by the Boston Gazette and inflamed the populous. Groups of colonists were looking for British soldiers to harass and the soldiers were expecting confrontations. It all came together and clashed on 5 March 1770.

Hugh White was a private in His Majesty’s 29th Regiment of Foot. He was 30 years old and had served in the British Army for 11 years. On the cold evening of Monday, 5 March 1770 he was stationed at a guard post near the Customs House when an argument began nearby. Edward Garrick was berating British Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch about an unpaid bill. Goldfinch had already paid the bill, so he ignored Garrick. Private White then warned Garrick to be more respectful of a British officer, but the argument escalated and became more physical. White left his post, challenged Garrick, and struck him on the head with his musket. (The “Brown Bess” musket weighs nearly 11 pounds.) Garrick’s companion, Bartholomew Broaders then confronted White.

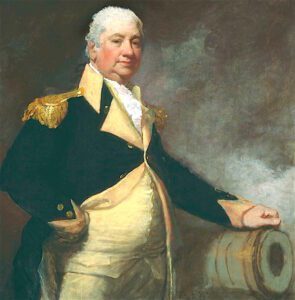

This activity attracted a crowd of civilians that were already angry and hostile. The crowd was rapidly growing and becoming more antagonistic. Nineteen-year-old bookseller Henry Knox (future Continental Army general) was on the scene and warned White: “if you fire, you must die for it.” The crowd reached about 50 in number and church bells were rung to call out more.

White retreated to the steps of the Customs House, loaded his musket, and threatened to fire if the crowd attacked him. The crowd led by mixed-race former slave, Crispus Attucks, was taunting White and pressing him to fire his weapon. White knew he was in danger and sent a runner to fetch help. Captain Thomas Preston dispatched one NCO and six privates under his command from the grenadier company of the 29th Regiment of Foot. They deployed to the scene with fixed bayonets. As they forced their way through the crowd to relieve Private White, Henry Knox, who was personally acquainted with many British officers, took Preston by the coat, and warned him; “For God’s sake, take care of your men. If they fire, you must die.” Preston replied that he was aware of the danger.

Once they reached Private White, Preston’s troops loaded their muskets and with fixed bayonets established a defensive line around White. By this time, the crowd was estimated to be between 300 and 400. They were taunting the soldiers by yelling for them to “fire,” throwing objects and snowballs and spitting at them. At this point, a heavy thrown object struck Private Hugh Montogomery knocking him down and causing him to drop his musket. When he recovered his weapon he shouted, “Damn you, fire!” and fired into the crowd.

There was a short pause, after which the soldiers fired a sporadic volley into the crowd. It was not a disciplined volley because Preston had not given an order to fire. Eleven civilians were struck. Three, Crispus Attucks, ropemaker Samuel Gray, and mariner James Caldwell, died instantly. Samuel Maverick, a 17-year-old apprentice ivory turner died the next morning. Irish immigrant Patrick Carr died two weeks later. Apprentice Christopher Monk was permanently crippled and died several years later.

The gunfire stunned the crowd, and although they left the immediate area, their numbers were still increasing in nearby streets. Captain Preston called out most of the 29th Regiment and set up defensive positions around the nearby State House. Acting Governor Thomas Hutchison was called to the scene but was forced into the State House by the crowd. From the balcony, Hutchison assured the crowd that there would be a fair inquiry into the incident if they would disperse and order was slowly restored.

True to his word, Hutchison began his investigation immediately and the next morning Preston and the eight soldiers were arrested. Boston’s Selectmen asked Hutchison to order all British troops to move to Fort William on Castle Island. The colonists held a town meeting which resulted in a request that all British troops be moved out of the city.

The 14th Regiment moved out about a week later. General Gage was convinced that the troops were doing more harm than good, and he ordered the 29th Regiment out of the city in May. This left Governor Hutchison without adequate means to police the city, and the citizens were very hostile towards British troops and their dependents.

On 27 March, the eight soldiers, Captain Preston, and four civilians were indicted for murder. The civilians had been in the Customs House and allegedly fired shots. Hutchison took advantage of the high tensions to justify delaying the trials until later in the year. This would seem on the surface to be a wise decision to allow passions to cool.

The first trial did not begin until late October 1770 and the intervening period was flooded with highly inflammatory and usually inaccurate information about the incident. Loyalists portrayed the crowd as “brutish” and spoiling for a fight and the soldiers as good guys. Boston patriots portrayed the exact opposite and used their publications to successfully stir up revolutionary fervor among the people.

The most famous artist depiction of the Boston Massacre was originally done by engraver Henry Pelham. Silversmith and engraver Paul Revere closely copied the Pelham image and is usually credited as the originator. The engraving shows Captain Preston ordering his men to fire. A musket is shown firing out of a window of the Customs Hall, which is labeled “Butcher’s Hall.” This engraving was published by the Boston Gazette and a colorized version was distributed throughout New England.

Anonymous pamphlets describing the Boston Massacre and other soldier/civilian confrontations were also published. Some claimed the British had planned to cause harm and indiscriminately fired on peaceful law-abiding citizens. Boston officials held back many of these publications to avoid tainting the jury pool. They did, however, send copies to other colonies and to London. Governor Hutchison published a pamphlet claiming Bostonians denied British law and were lawless. He also claimed that the colonists planned to ambush the soldiers. His pamphlet was published later than most of the others and had little effect on the public.

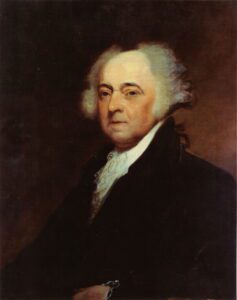

Finding a legal defense team was difficult since the government wanted to have a fair trial that would not be challenged by either side. Many lawyers refused the job, but the government finally convinced John Adams to be the lead defense attorney. He was joined by Josiah Quincy II after he was assured the Sons of Liberty would not object, and by Loyalist Robert Auchmuty. They were assisted by Sampson Salter Blowers who investigated the jury pool. Solicitor General Samuel Quincy and attorney Robert Treat Paine served as prosecutors.

Captain Preston was tried first and was acquitted. Despite contridictatory testimony, the jury was convinced that he had not ordered his troops to open fire.

The trial of the eight soldiers began on 27 November 1770. Adams told the jury to ignore the fact that the soldiers were British, and he denigrated the civilians. He said they were “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and molattoes, Irish teagues, and outlandish Jack Tarr’s.” He said the term “mob” was too respectable for them. He also claimed that Crispus Attucks grabbed a soldier’s bayonet and knocked the soldier down, which caused the shooting. This was contradicted by witnesses who stated Attucks was 12-15 feet away from the soldiers when the firing began. Adams also argued that the soldiers had a legal right to fight back and so were innocent.

Adams successfully convinced the jury and they acquitted six of the soldiers. The jury was swayed by the deathbed testimony of Irishman Patrick Carr who testified that he had never seen any soldiers bear as much as the British had. This is one of the earliest recorded uses of the “dying declaration” exception of the inadmissibility of hearsay evidence in the United States legal code.

Two soldiers, Hugh Montgomery, and Matthew Kilroy were convicted of manslaughter because there was overwhelming evidence that they had fired directly into the crowd. The penalty for manslaughter was death.

The convicted soldiers managed to get reduced sentences by pleading “benefit of clergy,” which exempted clergymen, including men with the ability to read or recite Biblical passages, from trial by secular courts. The benefit of clergy penalty for manslaughter was branding of the thumb in open court. This punishment was carried out on 14 December. The convicted read Bible passages and a red-hot iron was used to brand their thumbs with an “M” for manslaughter.

The four civilians were tried on 13 December. The main witness against them was a servant of one of the accused. This servant made claims that were soundly refuted by other witnesses and the four were acquitted. The servant, however, was later convicted of perjury, whipped, and banished from the colony.

The hostility between soldiers and Bostonians cooled down slightly, but only temporarily, after the trials. Boston activists used the massacre to build support for independence. Samuel Adams successfully campaigned to make 5 March an official “day of mourning.” He and others used these annual commemorations to stir up the citizens with fiery speeches to keep the memory of the massacre in the public eye.

It was five years before war began and some historians still argue about how much the Boston Massacre contributed to the beginning of war, but most believe it was a major factor. John Adams wrote that the “foundation of American independence was laid” on 5 March 1770. Later incidents such as the Gaspee Affair and the Boston Tea Party built on the effects of the Boston Massacre and convinced Americans to take up arms against King George III.

The Boston Massacre spawned a large amount of art and publications to commemorate the incident and to emphasize certain facts. It is often used to appropriately point out that a black man was one of the first to die for American independence. In 1888, the Boston Massacre Monument was erected on the Boston Common in memory of the men killed that day, and five of the victims were reinterred in a prominent grave in the Granary Burying Ground. The massacre is still reenacted annually by the Bostonian Society. The Old State House, the massacre site and the Granary Burying Ground are part of Boston’s Freedom Trail.

There have been many incidents in American history that have changed our world. The Boston Massacre, the burning of the White House, the firing on Fort Sumpter, the sinking of the USS Maine, the sinking of the SS Lusitania, the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the invasion of Korea, the TET Offensive, and 9/11 to mention only a few. As the years pass the passions and significance of those events fade from our national memory and become only words in a history book. Many young people don’t even know they happened. We should never forget the people who have died to make and keep us free. American history is filled with common people who displayed uncommon valor. The heroes, the leaders, and even the cowards and turncoats all deserve to be remembered.