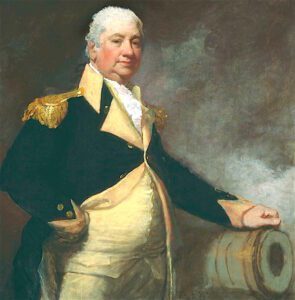

Henry Knox was a self-educated artillery officer and military engineer who reached the rank of Major General during the Revolutionary War. He was the first Secretary of War. He established formal artillery training, two military arsenals, and oversaw the beginnings of today’s National Guard system. He laid the groundwork for army and navy military academies. Despite his personal idealism about Native American rights, Knox oversaw wars to remove them from their ancestral lands. After retirement he earned a reputation as a heartless landlord. Henry Knox was imperfect, but he was a true American patriot, and a self-made American hero.

Henry Knox was born on 25 July 1750 in Boston Massachusetts, the seventh of ten children of William Knox and Mary Campbell Knox who were Ulster-Scot immigrants. William Knox died in the West Indies in 1762. Since Henry was the eldest male at home, he left the Boston Latin School to support the family. He became a clerk in a bookstore, becoming an avid reader, particularly of military subjects.

About 1768, Knox joined a local artillery company called “The Train.” In 1770 he testified in the trial of British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre, and in 1771 he opened his own bookstore, the London Book Store. His clientele consisted primarily of British officers and Tory ladies since he carried mostly British products. He established strong business ties with his British suppliers and developed personal relationships with his customers. He stocked and read books on military science and discussed military subjects with the officers who frequented his store.

The bookstore was successful, but profits plummeted after the Boston Port Bill and the boycott of British goods. I don’t think Knox was too worried about business at this point. He cofounded the Boston Grenadier Corps in 1772 and was a supporter of the “Sons of Liberty,” a group of anti-British agitators. It is not known if he took part in the 1773 Boston Tea Party, but he was involved in the lead-up to this act.

On 16 June 1774, Henry married Lucy Flucker despite the opposition of her parents who were Boston Loyalists. Her brother was in the British Army and the family tried to recruit Henry to the Loyalist cause. Henry and Lucy were devoted to each other for life despite long separations during his military days. However, she often visited him when he was in the field and they found enough time to have 13 children.

Henry and Lucy had to flee Boston in 1775 making Lucy essentially homeless until the British evacuated the city in 1776. Henry Knox joined the rebels besieging Boston, beginning his military career under the command of General Artemas Ward. He used his self-taught engineering skills to construct fortifications around Boston and he directed the rebel cannon fire during the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill.

George Washington arrived in July 1775 to take command of the Continental Army, and Knox began interacting with the officers organizing the army. He had no military commission, but Washington was impressed with his performance at Bunker Hill and his knowledge of engineering and artillery. Knox and Washington also developed a strong personal relationship that lasted a lifetime. One thing they had in common was stature. Both were much taller than the average for their times and both were powerfully built. They physically dominated any gathering.

While John Adams worked to get Knox a commission to command the artillery regiment, Washington was already seeking his advice. Washington was in dire need of more artillery and Knox suggested retrieving cannon from the recently captured forts of Ticonderoga and Crown Point in upstate New York. Despite the obvious hazards of such an expedition, Washington appointed Knox commander of artillery and gave him the job of moving the guns to Boston.

Ticonderoga was more than 300 miles away across the Berkshire Mountains. Knox and his party arrived on 5 December 1775 and organized the acquisition of guns, shot, powder and other supplies that had to be moved. The area was sparsely populated so finding drovers and draft animals was difficult.

The trek to Boston was arduous to say the least. They moved 60 tons of cannon and other armaments on ox-drawn sleds in bitter cold and deep snow, particularly in the mountains. Cannon sometimes broke through ice covered rivers, but they managed to save them all. They delivered 50 cannon to Washington’s headquarters on 27 January 1776. Historian Victor Brooks called this expedition “one of the most stupendous feats of logistics” of the entire war.

Cannon were now deployed to Dorchester Heights which commanded Boston Harbor and forced the British to withdraw from Boston. All British troops, ships, and supporters evacuated the city, including Lucy Knox’s parents who went to England and never returned.

With the siege of Boston broken Knox, now a colonel, supervised the improvement of defenses in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York City. Washington moved his forces to protect New York City and Knox re-joined the army there.

Knox was with the army throughout the New York and New Jersey Campaigns, including the loss of New York City when the British Fleet arrived with 30,000 troops. The Americans numbered about 18,000 with little experience and were forced to abandon the city. Knox’s artillery numbered about 520 men with about 120 cannon.

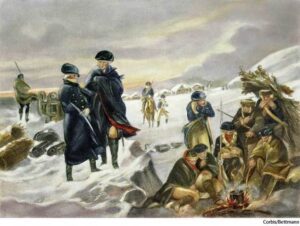

The Americans retreated across the Delaware River at Trenton, New Jersey on 8 December 1776, and seized all the boats along the river to keep the British from following. They were poorly clothed and poorly armed. Morale was in the tank, and Washington realized that he needed a victory to give his troops hope. This is when the Christmas Night “Crossing of the Delaware” operation was conceived.

Colonel Knox was in command of logistics for this operation and he again showed exceptional organizational and operational skills. Despite the river ice and bitter cold, he managed to transport 2,500 men, their horses, and artillery across the river without a single loss. Following the battle, Knox had to return the men, their horses and artillery, as well as 1,000 captives and captured supplies. This was all accomplished by the afternoon of 26 December.

This spectacular operation improved morale considerably and provided them with some needed provisions. Henry Knox was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General for his performance. Washington was, however, in danger of losing his army due to expiring enlistments and the fact that the troops had not been paid. Washington wrote to his friend Robert Morris for help and he sent $50,000 which saved the army.

Washington was now confident enough to move into New Jersey by re-crossing the Delaware to draw the British into battle. Cornwallis followed and believed he had Washington trapped between the Delaware and Trenton, but Washington outsmarted him and moved towards Princeton. On 3 January 1777, the Americans attacked Cornwallis, but were driven back. Washington rallied his troops, counter-attacked, and won the Battle of Princeton. Knox and his artillery were key to this victory and earned him a commendation.

Once the army went into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, Knox was sent to raise an artillery battalion in Massachusetts and to establish an arsenal. He raised the unit and an arsenal was established at Springfield, which is now known as the Springfield Armory. About this time there was an effort to replace Knox with a qualified French volunteer, but Washington and his officers managed to block this. The French officer received a different appointment in the army but was killed in an accident later in the year.

In 1777 British General Sir William Howe moved his army of 15,000 by sea from New York City to Delaware. He then moved into Pennsylvania to capture Philadelphia, the American capital. Washington rapidly moved the Continental Army to set up blocking forces at Brandywine Creek. In September, Howe outgeneraled Washington and flanked the Americans. Frantic American repositioning saved the army from annihilation.

The British moved into Philadelphia, but the Continental Congress had already moved to York, Pennsylvania. Washington knew he had the strength for only one attempt to force the British out of Philadelphia before winter arrived. He chose to attack the British at Germantown in October.

Washington mounted a daring offensive that depended on stealthy movements, but his army was not trained well enough to successfully execute the plan. They were detected giving the British time to mount their defense. Despite repeated American assaults, heavy artillery fire, and heavy casualties the British could not be dislodged.

General Knox and his artillery were involved in both Brandywine and Germantown. They had a limited number of cannon that Knox deployed wisely for maximum benefit, but it was not enough to avoid the defeats.

The British in December 1777 dispatched 10,000 troops from Philadelphia in an effort to destroy Washington’s army. The Americans intercepted them and a ruse by Washington allowed them the time needed to establish an impregnable line near Whitemarsh. The British were unable to penetrate or flank the line, so they returned to Philadelphia to warm, comfortable winter quarters with lots of food. The Americans, battered, tired, hungry, and with inadequate supplies, wintered at Valley Forge.

At Valley Forge, Knox organized and constructed forts to defend the encampment. The Americans erected 1,000 log huts to house 12,000 troops, but by February, death, disease, and desertions reduced that number to 6,000. However, the winter was not wasted because Prussian Officer Baron Friedrich Von Steuben arrived and trained the troops, turning them into an effective, disciplined army.

Knox was given leave from Valley Forge to visit his family in Massachusetts, but more importantly to try to speed supplies for the army from New England. The latter was not particularly successful, and Knox returned to Valley Forge. He assisted Von Steuben with the training, particularly of the artillery.

In February 1778, the Franco-American pact tilted the advantage in the war to the Americans, and in June the British were ordered to evacuate Philadelphia and to consolidate in New York. Washington moved to attack the British during their retreat and sent a third of his army ahead under the command of Major General Charles Lee to engage them. Lee botched the attack and the British counter-attacked, but Washington arrived in time to establish a strong defensive line at Monmouth, New Jersey. The British disengaged and continued their retreat. Washington again commended Knox for the artillery’s performance.

The army was generally inactive during the rest of 1778, and Knox set up artillery winter quarters at Pluckemin, New Jersey. There he established the Continental Army’s first artillery and officer training school. Through the summer of 1779 Knox trained more than 1,000 soldiers despite low morale and scarce supplies. Conditions were even worse during the winter of 1779-80.

The northern war was at a stalemate in 1780 and the war’s main action had moved into the south. Knox made many trips to the northern states in an effort to increase the flow of men and supplies to the army with only moderate success.

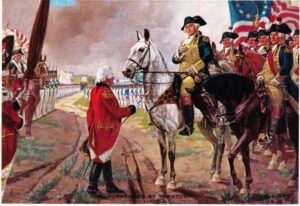

In 1781, Knox accompanied the army south, and participated in the siege of Yorktown, Virginia where he directed the placement and aiming of rebel artillery. He established a friendship with the French artillery commander, the Marquis de Chastellux. General Washington cited them both for their roles in the siege and recommended that Knox be promoted.

Cornwallis surrendered on 19 October 1781, and soon afterward Knox was promoted to Major General—a well-deserved promotion. Knox was now the youngest major general in the army. In 1782 Knox and Congressman Gouverneur Morris were assigned to negotiate prisoner exchanges with the British but these initial negotiations failed.

In August 1782 Knox took command of West Point and a month later his nine-month-old son died which put him in a state of depression. Despite this he and Secretary of War Benjamin Lincoln started negotiations with the Confederation Congress about pensions and overdue compensation for the military. Sadly, Congress was unwilling to seriously address the problem

Knox drafted a paper about the possible ramifications of congressional inaction, which started some talking of mutiny. Luckily, this mutiny talk was squelched by General Washington and his senior officers. Knox and others became staunch proponents of a stronger national government because of the inability of the Confederation Congress to act on much of anything.

In the fall of 1783, Knox and his troops shadowed the British that were evacuating New York until they were FINALLY GONE. On 21 November, Knox led American troops into the liberated New York City.

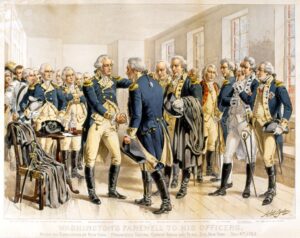

On 4 December, the Continental officers assembled at Fraunces Tavern to take leave of their Commander, George Washington. Knox stood next to Washington, during Washington’s farewell address. When Washington resigned his commission on 23 December, Knox became the senior officer of the army.

The post of Secretary of War became available when Benjamin Lincoln resigned in November 1783, and Lincoln recommended Knox for the job. Even though congress had lots of warning about the resignation, they were again unwilling to act, and they did not want a peacetime army. They wanted to rely on militia. Knox saw this as a good time to resign his commission since he could see that nothing good was likely to be done.

Knox returned to Massachusetts and the family established a home in Dorchester. He also was appointed as the state’s official for disposing of confiscated Tory land. Using unethical rigging of the process he assembled a multi-million-acre empire in Maine (then part of Massachusetts), including land confiscated from his Tory in-laws.

Congress finally appointed Knox as the Confederation’s second Secretary of War on 8 March 1785. Civilian life had been good to Knox and he was now of “immense girth” weighing about 300 pounds. His department was a mess because congress could not agree on much of anything and were still fearful of a “standing army.” Knox made many proposals, most of which were rejected or ignored.

The 1786 “Shays’ Rebellion” broke out in Massachusetts and the rebels threatened the Springfield Arsenal. Benjamin Lincoln had to raise a militia force to put down the rebellion, which highlighted the weakness of the military and the ineffectiveness of the Articles of Confederation.

All the problems resulted in the Constitutional Convention that gave us our Constitution. When the convention started, Knox sent a draft to George Washington and encouraged him to attend the convention calling him “Father of His Country” — the first known use of this term. Washington chaired the convention and we became the United States of America.

Knox was touted as a candidate for vice president, but he chose not to run. Instead, Knox was appointed the first Secretary of War of the newly established republic during the administration of George Washington.

During his tenure as Secretary of War Knox implemented the Militia Act of 1792 setting up a force of 450,000 members; he established a second arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (Now West Virginia); he established the US Navy; coastal fortifications; and a standing army. He also suggested the establishment of military academies to train competent and motivated officers. However the Military Academy at West Point wasn’t established until in 1802 and the Naval Academy at Annapolis was finally established in 1845.

His tenure was unfortunately dominated by relations with Native American tribes. He was responsible for these relationships and his personal views favored the tribes. He believed the tribes owned the land they had inhabited for thousands of years and that this ownership should be recognized by the US Government.

Things did not work out the way Knox had hoped because virtually nobody agreed with him. The “Doctrine of Discovery” governed the taking of Native lands. The tribes did not take this laying down and the clash of cultures resulted in the “Cherokee-American Wars” and the “Northwest Indian War.”

The Northwest tribes were supported by the British who still occupied bases in violation of the “Treaty of Paris” which ended the Revolutionary War. The indian conflicts were not going good so in October 1790 Knox organized a campaign commanded by General Josiah Harmer into the Northwest Territory. This campaign failed. A second campaign led by Governor Arthur St. Clair resulted in the worst defeat the Army ever suffered because of a failure to adequately supply them. As a result Knox was widely accused of not protecting the frontier.

Knox wanted to close the problem before leaving office and organized an expedition led by General “Mad” Anthony Wayne. This campaign was victorious at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers. This victory led to the Treaty of Greenville which forced the defeated tribes to cede land in the Ohio area. (We know that this was just the beginning of bloody wars and broken treaties for about another 100 years.) According to Knox’s writings, he accurately believed that Indian wars would continue indefinitely.

After nearly 20 years of service to our country, Knox tendered his resignation to President Washington on 28 December 1794. The President accepted the resignation with “regret.” Timothy Pickering was appointed to replace Knox and took office on 2 January 1795.

The Knox family built a magnificent mansion on their Maine property, which they named “Montpelier.” He speculated in many endeavors, but mostly in frontier land. His holdings reached from Maine to the Ohio Valley, although most of his property was in Maine. Knox always claimed to treat settlers on his Maine property fairly and humanely, but he used intermediaries to evict those who did not pay their rent or squatted on his land. He became so unpopular that settlers threatened to burn his mansion. Many of his speculations failed and he had to sell off land to cover his losses. Many of our founders lost huge sums in frontier land speculations.

Henry Knox died at home on 25 October 1806. He died three days after swallowing a chicken bone which lodged in his throat causing an infection. He was buried on his estate with full military honors. Lucy died in 1824. She had been forced to sell off more property to pay creditors of Henry’s insolvent estate. The couple had been blessed with 13 children, but only one survived to adulthood.

Henry Knox was a self-made man who devoted most of his adult life fighting for independence and serving his new country. He achieved fame and honors as a military leader, and as a member of the first presidential administration. He was a giant among giants. Washington was the Father of Our Country, but Knox was the Father of our Military. Unfortunately, he had to direct wars against Native American tribes despite his personal support of their right to their lands.

Knox was a contradiction in many ways. When he and Lucy were forced out of Boston in 1775, British troops were quartered in, and trashed their home, and looted his bookstore. However, despite financial hardships, he paid the last payment of 1,000 pounds to Longman Printers in London to cover the price of books that he never received. Payment was a matter of honor. After retirement, however, he was remembered as a grasping tyrant, and was the model for the character, Col. Pyncheon in Hawthorne’s “The House of Seven Gables”

Henry Knox, like all of us, was flawed, but he should not be rejected because of terrible behavior during his short later years. Those years do not diminish the fact that this man risked his life and his possessions to play a vital role in the war for independence and participated in the establishment and stabilization of the new government. The amazing thing is that he was self-educated with no formal military or organizational training. Henry Knox was a true patriot and an American hero