Today we take easy travel around our great country for granted. My wife and I easily drove from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania to Sacramento, California in four days. When I visit my Missouri hometown, I am still amazed that most roads are now paved. Interstate highways that were being constructed while I was in college now serve every section of the country. When I was first married and traveled between St. Louis, Missouri and Silver Spring, Maryland, the trip was still made on US 40 through all the towns. Now it is mostly on I-70. This is how much travel has improved just since World War II.

Travel in the 17th and 18th centuries was, however, a nightmare. “Roads” were often nothing more than glorified foot paths. Travel was difficult, expensive, and often dangerous so most travelers were government officials, merchants and planters who did so for business or official duty. The poor rarely, if ever, traveled away from their homes.

Most people migrated to the New World from Europe, a trip that was extremely unpleasant and dangerous. The Atlantic crossing took at least six to eight weeks in good weather. The ships were small sailing vessels that were never stable. They rocked with every small wave and in storms were very unstable and in risk of sinking. The passengers were in cramped quarters, and many suffered seasickness for the entire journey. Any illness that popped up was shared by most of the passengers with some dying during the voyage. Piracy was always a threat to early shipping.

The cost of crossing the Atlantic was so high that only the well-to-do could afford passage. The people who could afford the cost usually made the trip to reestablish their way of life in the New World. Those wanting to travel to America for a better life were usually poor and could not afford passage. Most sold themselves, and even their families, into Indentured Servitude, becoming virtual slaves for a set period to pay for their crossing.

In addition to Indentured Servants, convicts were deported to the colonies. The English were trying to solve their crime problem by getting rid of the criminals. Between 1718 and 1775 over 52,000 convicts were transported to America, mainly to Maryland and Virginia, to be sold as slaves. Convicts made up a quarter of the British immigrants during the 18th century.

Once migrants reached the New World, they found a transportation system even more primitive than in Britain and they had to adjust to that reality.

The usual mode of travel in the colonies was simply walking, and people often walked amazing distances to get supplies or to visit. Travel by horseback was popular among those who could afford a horse. Depending on breeding and capabilities, a horse cost from 5 to 1,000 British pounds and many colonists bought a horse as soon as they could afford the price and the upkeep.

Successful farmers and merchants often had wheeled wagons and draught animals to move equipment and supplies. The Conestoga Wagon, which became famous later, was used to transport the heaviest loads. Wagons were pulled by teams of horses, mules, or oxen.

The well-to-do often had horse-drawn carriages for travel. Like autos today, these carriages, and in particular the horses, could be a public display of wealth. For instance, on 20 June 1775, Thomas Jefferson arrived in Philadelphia to serve in the Second Continental Congress in an ornate carriage drawn by a team of four matched horses. That was a statement for sure.

No matter the mode, travel in the colonies was slow. The speed of walking is about 2 to 4 miles per hour, a good horse can consistently walk about 4 mph and trot 8 to 12 mph, horse-drawn wagons about 4 to 8 mph, oxen drawn wagons about 2 mph and carriages about 2 to 4 mph. These speeds are averages on a flat, smooth surface. Roads were usually very rough with wagon wheel ruts as much as two-feet-deep, which was dangerous for men and animals. It was easy for animals to break a leg, and for walkers to break an ankle or leg. Wagons and carriages were rough rides on these roads and broken wheels and axles were common.

The first English colonies established in North America were Virginia in 1607 and Massachusetts in 1620. As more settlers arrived, more settlements were established along the Atlantic coast. By 1732 13 colonies had been established. These colonies were organized into three regions known as the Northern, Middle, and Southern. The Northern Colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire quickly became known as New England. The Middle Colonies consisted of New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. The Southern Colonies were Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

Trade between the three regions and with England was essential and was growing rapidly. Goods were moving easily in and out of coastal ports, but the necessity of moving goods, people, and mail between ports and to other cities demanded a more reliable road network. This was a tall order, however, because most of the countryside outside the towns and cities was still wilderness.

Responsibility for road and bridge construction and maintenance was given to county courts. This was a logical move since the counties already had working governments, but their effectiveness varied considerably. Most also had a limited tax base. I do genealogical research, so I go through mountains of county records. It amazes me that most early counties had quickly set up governing bodies, courts, and law enforcement. They handled arrests, incarcerations, wills, estates, marriages, divorces, criminal and civil trials despite being in a wilderness. There were local trails and crude roads in the settlements and towns but little more.

Despite the problems, counties took the road and bridge business seriously. Courts appointed locals to build and maintain specific sections of roads and bridges, but it was difficult for them to track the work. There was a wide range of ability and honesty. Some did so poorly that they had to be replaced, and some took the money and disappeared.

Most roads were simply paths that were cleared of most trees and brush. Local materials had to be used, and seldom was there a way to hard surface roads. This meant during wet weather the roads turned into quagmires and became severely rutted.

There were no nationwide road and bridge standards and bridges were a real problem. Local workers rarely knew enough about bridge construction to put up a structure that was adequate in all conditions. They were generally able to put up a bridge that accommodated light traffic in good weather. Some of these bridges collapsed under heavy loads and many were washed away during heavy storms.

There was no master plan for a road network that connected the counties, much less connect the major cities and ports. Roads were being built to facilitate movement in local areas, and travel was still a nightmare.

The south presented a real problem for north-south road construction because of the long coastal shorelines, and long wide rivers, which were formidable obstacles. In the Tidewater areas most east-west travel and commerce moved by boat. This waterborne system of movement was very efficient and cheap but north-south movement was difficult. Roads had to parallel the rivers until the river was narrow enough to construct a bridge. Long bridges were quite difficult to build because of inadequate materials and limited engineering skills.

Ferries were often used to cross rivers because they could be established rapidly and easily. They had capacity limitations, but many could move substantial amounts of goods in short periods of time. In 1862 General Robert E Lee crossed 35,000 combat troops at White’s Ferry on the upper Potomac River to fight at Antietam and again when he withdrew.

Although long bridges can be built today, Tidewater roads still mostly follow the original routes. However, now there are a few very long bridges such as the Chesapeake Bay Bridge at Annapolis, Maryland and the 17-mile-long bridges and tunnels across the Chesapeake Bay that connects the Delmarva Peninsula and Virginia.

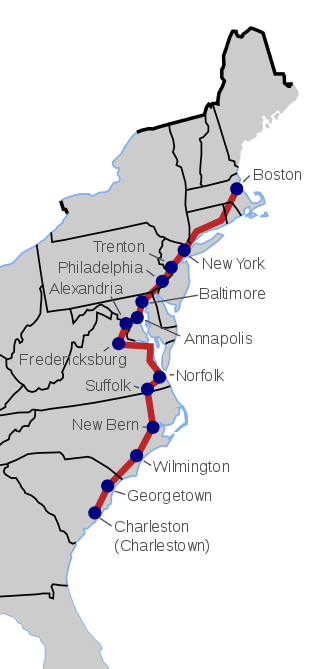

The first serious effort to connect all 13 colonies with a usable road came in the mid 17th Century when King Charles II ordered a road constructed connecting all 13 colonies. The road was originally planned to connect the major cities along the Atlantic coast—Boston, Massachusetts to Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston was established in 1670 and was originally known as Charlestown.

The thinking behind the King’s Road was quite forward-looking and was driven, in part, by the growing necessity to move mail reliably and safely. Mail was being delivered within population centers, but it was a maze of roads and paths that inter-connected even nearby towns.

Construction was once again the responsibility of county courts so there was a wide range in the quality of the work. The quality of the road was obviously also dependent on terrain. The problems of building along the coast in the southern states is much different than in rocky New England.

The King’s Road was roughly 1,300 miles long. Most sources indicate that most construction occurred between 1673 to 1753. The roads in New England and New York City were the most advanced at the start. The existing road between Boston and New York City followed the Pequot Indian Path. It was known as the Boston Post Road in recognition of the movement of mail between Boston and New York City. The Boston Post Road became part of the King’s Road when it was widened and smoothed to accommodate carriages.

Males over the age of 16 were required by law to work a set number of days on the road, but the details differed by state. Forced labor is not usually the best, although a few states continued this requirement into the 20th Century.

Bridges were again a bigger problem than roads, and counties were required to build bridges over rivers and other natural obstructions. They were usually constructed using wooden timbers. Bridge design was again rudimentary. Some collapsed under heavy loads, and many were washed away. Bridges were high maintenance items, but they were built and rebuilt as needed.

As construction of King’s Road progressed, portions of it and some bridges charged a toll to help pay for maintenance. Some counties constructed roads parallel to the King’s Road to bypass the tolls, and the bypasses were usually better quality than King’s Road. Many cities built their own roads to the coastal ports to avoid the fees for a lesser quality road.

King’s Road maintenance quickly deteriorated after completion. This was due to many factors but the most important was the lack of inter-colony management. Like everything else in life, somebody must be in charge to accomplish anything.

Today, US Route 1 and US Route 17 were built on the King’s Road route in the south. Farther north, US Route 1, US Route 20, US Route 206, and US Route 13 follow the King’s Road. Many state roads were also constructed on the King’s Road route.

Interest in a north-south Road began to wane with the beginning of major migration to the west, and the need to provide roads for that migration. Early explorers and trappers followed Indian trails west and found fertile ground, and open spaces occupied by Indian tribes. For years most people in the Americas had known little about what lay west over the mountains, but as the explorers and trappers returned and spoke of vast amounts of fertile land, people wanted to start the long and dangerous trek west.

The need and desire to move west away from civilization was in the soul of Americans from the start of colonization. My own ancestors migrated from Virginia into what became Tennessee in the early 18th Century to “get away from the crowding and high taxes” in the east.

The Appalachian Mountains were a formidable obstacle to western migration. Moving entire households was much different than trappers moving on foot with a minimum of supplies. The trek was so difficult that some early migrants gave up before crossing the mountains and settled in western Virginia and western Pennsylvania.

The earliest route to Kentucky was the Wilderness Road which was established by Daniel Boone. Boone and his frontiersmen linked up old Indian paths with trails used for centuries by herds of buffalo. (Yes, buffalo were in much of the east in early America.) In the beginning it was a road in name only, but it was later widened to accommodate wagons. The trip was long—about 800 miles from Philadelphia and it was dangerous.

The Wilderness Road passed through the Cumberland Gap, a natural pass in the Appalachian Mountains. In 1773, Boone and his family led a group of families through the gap into Kentucky. They were followed by thousands of settlers in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s.

The Wilderness Road was the main route to present day Kentucky and Tennessee for years. The population of Kentucky was 73,000 in 1790 (first census) and more than 220,000 in 1800, which shows how much the road was used.

Boone’s Wilderness Road operated decades before the 1811 National Road (today US 40) and the 1817 Erie Canal. Those routes opened the Northwest Territory (Midwest) to massive migration.

The relentless move west had begun and continued for more than another 100 years. Americans were just getting started. Kentucky and Tennessee were early new states, and the great cities of the Midwest were founded and became major centers of industry and business.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase essentially doubled the size of the United States. Most of this territory was wilderness known only to trappers and a few explorers. President Thomas Jefferson authorized the Lewis and Clarke Expedition to explore and map much of the territory to show the public that the 15-million-dollar cost had not been wasted.

The only towns in the Louisiana Territory hugged the shores of the Mississippi River but commerce already moved on that mighty river to the well-established port of New Orleans.

Lewis and Clarke launched their expedition from the major trading center of St. Louis at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Their expedition consisted of 45 men that were experienced in many sciences and experienced frontiersmen.

The expedition moved up the Missouri River and traveled about 8,000 miles in two years. Their findings launched massive immigration to the west. There were no roads, but wagon trains traveled trails that became famous in American history-the Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, the California Trail to name just a few. Leaving from St. Joseph, Missouri west coast migrants faced a 2,000-mile-long trek of 4-6 months. These migrants faced hunger, Indian raids, disease, accidents, and death, but they kept coming and populated the far western states and the territory in between.

The National Road, in many places now known as US Route 40, was built between 1811 and 1834 to reach the western settlements. It was federally funded because George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian Road was necessary to unify the young country.

Poor people traveled west by wagon train. The wealthy could travel by ship. From New York to San Francisco, it was an expensive 4-to-6-week trip of over 7,000 miles around Cape Horn. This too was a hazardous and difficult trip. The weather, particularly around Cape Horn, can be severe and many of the migrants died at sea.

The roads west of the Appalachian Mountains were slow to develop and travel remained difficult, dangerous, and generally unpleasant into the 20th century.

By 1912, the Nation’s highways were just emerging from the “Dark Ages” of road building in the second half of the 19th Century. Railroads were being rapidly constructed and dominated interstate transportation of people and goods. Roads were primarily of local interest. Outside cities, “market roads” were maintained, for better or worse, by counties or townships.

On 1 July 1913, a group of automobile enthusiasts and industry officials established the Lincoln Highway Association “to procure the establishment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful traffic of all description without toll charges.” In its time, the Lincoln Highway, which linked New York City and San Francisco, would become the Nation’s premier highway, as well-known as U.S. 66 became and as well-known as I-80 and I-95 are today.

The Federal-aid highway program would not begin until 1916 and, because of structural problems and the advent of World War I in 1917, would not accomplish much until 1921. The country had about 2,199,600 miles of rural roads and only 190,476 miles (8.66 percent of the total) had improved surfaces of gravel, stone, sand-clay, brick, shells, oiled earth, or bitumen. Many people thought of interstate roads as “peacock alleys” intended for the enjoyment of wealthy travelers who had time to ride around the country in their automobiles.

It was not until after World War II that modern American roads and highways were established. During the war, General Dwight D. Eisenhower noted how well the German military moved on the Autobahn highway system, and he became convinced that the US needed a similar highway system.

Eisenhower became president in 1953, and his administration developed a proposal for an interstate highway system, eventually resulting in the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. Unlike earlier American highways, the interstates were designed to be an all-freeway system, with nationally unified standards for construction and signage. While some older freeways were adopted into the system, most of the routes were completely new construction.

Construction of the original Interstate Highway System was proclaimed complete in 1992, despite deviations from the original 1956 plan and several stretches that did not fully conform with federal standards.

The interstate system has continued to expand and grow as additional federal funding was provided for new routes to be added, and many more routes are currently either being planned or under construction.

Interstate highways are owned by the states in which they were built but must meet Federal standards. The standards include controlled access, physical barriers, or median strips between lanes of oncoming traffic, breakdown lanes, no traffic lights, and federally designed traffic signs.

This article covers many years and documents how long it took to establish a coherent and reliable highway system in the country. We now have an integrated system of road, rail, and water. It’s not perfect but when not micro-managed, it continues to improve. Although I started out about early American transportation, it seemed to slide into modern times for a more complete picture. I hope you will forgive my insertion of personal information.