Lord Dunmore (born John Murray) was Royal Governor of Virginia before and for a brief time after the American Revolutionary War began. In 1774 Dunmore had organized a successful military campaign against a hostile Indian confederation in the frontier that some historians believe had a hidden agenda. They believe that Dunmore manipulated the Indians to begin raids so he could lead the Virginia militia to their defeat thereby reducing the number of Colonists available to oppose the British military. If that was his plan it failed miserably as the militia soundly defeated the Indians.

John Murray was a Scottish peer and the 4th Earl of Dunmore. He was an experienced British military officer, who served as Royal Governor of New York in 1770 and1771. He became Royal Governor of Virginia in 1771 and served until 1775. He was forced out of Virginia and after returning to England was eventually reassigned to be Royal Governor of the Bahamas 1787-1796.

Like most royal governors Dunmore used his position to enrich himself and to enjoy the social interaction with the occupying British upper echelon officers and the colonial elite class. His sons attended the College of William and Mary. His spouse, Lady Charlotte, was quite popular, but he was imperious and overbearing.

The royal governors were also expected to keep the peace in the colonies, and they had access to British military forces to do that. Dunmore also had the power to control the Virginia House of Burgesses and with revolution brewing he exercised that authority often.

The British had tried to control the American Indian tribes, but the Indians resisted because they did not appreciate being forced from their ancestral lands. The British made several treaties with the Indians, but whites persisted in settling in Indian land anyway. The Indians responded by conducting raids and killing the settlers, which resulted in British military retaliation. Both sides were brutal and vicious. (We know this pattern was continued when the new US Government was established.)

The 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, NY was between the British and the Iroquois Tribe. The Iroquois were forced to give up all their land east and south of the Ohio River. The problem was that other tribes in the area did not give up their land, which resulted in open warfare when white settlers started moving in. The Shawnee Tribe was actually trying to drive the British back to the east side of the Appalachian Mountains. They hoped that would permanently stop the white westward movement.

To maximize their effective strength, the Indians formed a confederation of Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Delaware, Wyandot, and Mingo tribes. They were commanded by the great Shawnee War Chief, Cornstalk. Cornstalk was a born leader who generally favored conciliation but was an experienced and capable warrior who would fight to the death if necessary.

When Captain John Connolly, commander of Fort Pitt (formerly Fort Duquesne and present-day Pittsburg, PA) prepared to retaliate by attacking the Indians, Lord Dunmore offered assistance. Dunmore’s offer was not what it appeared to be. His real goal was to prevent Pennsylvania’s expansion into modern-day West Virginia and Kentucky. He intended to insert Virginia militia into the area to safely open it to white settlement. This would also allow him to enrich himself through land speculation.

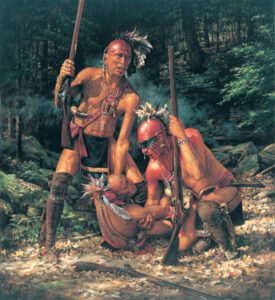

Lord Dunmore requested and got authority from the House of Burgesses to conduct war against the Indian Confederation. He recruited about 2,500 Virginia Militia volunteers including nearly 1,000 from the Shenandoah Valley. The Valley men were rugged and tough frontiersmen who lived on the edge of civilization. They were much like the Indians and were known to be fierce and brutal warriors. They were very independent and undisciplined by military standards.

Dunmore was an experienced British military officer and planned a very good campaign. He would take about 1,700 troops to Fort Pitt where they would obtain boats and move down the Ohio River to the intersection with the Kanawha River. Militia General Andrew Lewis with about 800 valley men would move from Camp Union (present-day Lewisburg, WV) to the same point, but he would travel overland. This route was through some of the most rugged terrain in the frontier.

General Lewis was an experienced and courageous fighter who was always anxious to engage the enemy. He commanded three “regiments” commanded by Colonels Charles Lewis (his brother), William Fleming, and John Field.

Interestingly, General Lewis’ small army produced seven Continental Army generals, several men who served with Colonel Clark in the struggle to capture Vincennes, the cadre of Daniel Morgan’s rifle regiment (one of the best Revolutionary units) and led the mountain men who defeated the Loyalists on King’s Mountain (the first American victory in the south). Five from this unit would become state governors.

General Lewis moved out of Camp Union on 6 September 1774 and after a demanding march arrived at the rendezvous site, known as Point Pleasant, on 6 October. Dunmore should have already occupied this site, but he was not there when Lewis arrived. Dunmore had become indecisive and was changing tactics by the day. By late September he had again decided to move to Point Pleasant.

Lewis was in the dark about Dunmore’s location, so he sent scouts to find him, and he began work on fortifications and securing his supplies. Chief Cornstalk was the one person who knew where everybody was because he had scouts shadowing all of them from the start. He recognized he could and should attack Lewis before the link-up with Dunmore and was organizing his attack.

Lewis believed the enemy to be far away and did not follow the most basic of military maxims: he did not post guards nor send out patrols. Unknown to Lewis, Cornstalk had crossed the Ohio on 10 October with nearly 1,000 warriors. He was encamped only 2 miles from Lewis and was preparing a dawn attack against the sleeping militia.

By an amazing stroke of luck, two of Lewis’ men were out for an early morning hunt for fresh meat. They ran into the main Indian force. One was killed but the other was able to alert the camp. Lewis believed the attackers were only scouts and moved a small force forward to confront them. They were met with a hail of gunfire and forced to retreat.

Lewis established a defensive line with his flanks anchored by the two rivers, which denied Cornstalk the option of easily flanking the Virginians. Flanking was known to be Cornstalk’s favorite battle tactic.

After several attacks and counterattacks, the fighting became hand-to-hand using clubs, tomahawks, knives, and bare hands. This fighting was savage and exhausting and could not be sustained indefinitely. About noon both sides occupied strong positions and the fighting became longer-range. To stand meant death.

Lewis detached two companies to flank Cornstalk by moving up the Kanawha and wading/swimming the river. This flank attack shocked the Indians. Cornstalk mistakenly believed he was being attacked by Dunmore who he knew was moving toward Point Pleasant. Cornstalk reacted quickly and left enough warriors to continue the fight on two fronts while he moved his wounded back across the Ohio. He then effected a total withdrawal by dark. This was an amazing military operation to accomplish while under attack.

The lead elements of Dunmore’s force arrived about midnight and found the defenders were totally exhausted having fought a pitched battle for nearly 12 hours without rest. The only medical officer, Colonel Fleming had been mortally wounded and the wounded were suffering greatly.

The battle was a Colonial victory but at a high cost–about 20 percent casualties. Seventy-five were killed and about 140 wounded. Indian casualties were hard to determine but were high. They left 33 dead on the field and disposed of many bodies in the river. The Virginians placed 18 Indian scalps on a pole by the river.

General Lewis buried his dead, completed his fortifications, and cared for the wounded until 17 October. At that point he left a powerful force to guard the wounded and crossed the Ohio with the rest of his army. They intended to exact vengeance and were prepared for heavy fighting.

Before engaging the Indians, a messenger from Lord Dunmore arrived. The messenger carried orders for Lewis to halt his march because Dunmore was drawing up a new treaty with the Indians. Lewis’ troops were openly incensed by this turn of events.

Negotiations had begun because Chief Cornstalk had not been idle since the Point Pleasant battle. He tried to rally his followers with the message that the fight had to continue no matter the losses or they were “doomed.” He found no support from his allies and he knew the Shawnee could not win alone. He left the council saying, “Since you will not fight, I go and make peace.”

Cornstalk opened negotiations with Dunmore who was greatly impressed by him because he was such a good negotiator. Cornstalk promised to free all white prisoners, to not hunt south of the Ohio River, and to stop attacking boats on the river. Dunmore promised no more whites would enter what today is known as Kentucky, and no settlers would move north of the Ohio. Obviously, neither of them could guarantee these provisions and both probably knew the treaty would not last long

Lord Dunmore than met with Lewis’ troops to complement them on their victory, but Lewis had to guard the Governor because his men were threatening him. This meeting did not last long.

Lewis’ troops moved back to Point Pleasant arriving on 28 October and his army was disbanded on 4 November 1774. Governor Lord Dunmore claimed he had “saved” the frontier and gave little credit to Lewis and his troops. The Virginia House of Burgesses extravagantly praised Dunmore.

This was the time when separation from Britain was gaining traction, and many questioned Lord Dunmore’s motives on the frontier. Most correctly believed he expected to profit financially from his war, but many believed he was attempting to distract attention from the growing revolutionary movement. A few believed he had manipulated the Indians into war to get rid of as many potential revolutionary soldiers as possible.

These claims probably gave Dunmore too much credit for strategic thinking since he was not known to be a particularly deep thinker. Personally, I believe he delayed his link-up with Lewis at Point Pleasant so that Lewis would have to do the hard fighting. There is no evidence that he had other motives.

I do know that Cornstalk played Dunmore like a fiddle. Cornstalk knew where all the forces were at any given time, which allowed him to slow Dunmore’s advance towards Point Pleasant by beginning long-distant negotiations. This gave Cornstalk the time to destroy Lewis’ force and then turn 180 degrees to attack Dunmore. Alternatively, as actually happened, if he lost the battle with Lewis, he could still negotiate with Dunmore.

Cornstalk did think strategically and tactically, and was an accomplished diplomat. He had an excellent plan and kept at least one step ahead of Dunmore. Cornstalk nearly pulled off a great victory. Those two early morning hunters accidently tilted the battle in favor of the Virginians.

Little attention was paid to the Dunmore-Cornstalk treaty. Settlers flooded into the Ohio River Valley, and into Kentucky. Indians retaliated and this was the beginning of the Indian wars that would occupy the US Military for more than 100 years. War, disease, and settlement were the Three Horsemen of the Indian Apocalypse.

Following his war, Lord Dunmore returned to Royal Governor duties. He was loyal to the Crown and bitterly opposed the revolutionary movement in Virginia. On 7 June 1775, he was forced to abandon Williamsburg and fled to the warship HMS Fowey in the harbor at Yorktown.

Dunmore tried to rule from the Fowey, but this was ineffective and impractical. By May 1776 he was forced to move to Gwynn’s Island. On 8 July Brigadier General Andrew Lewis commanded a force that opened a tremendous bombardment on Dunmore’s ships and camps, and on 6 August 1776 Dunmore sailed for England.

Chief Cornstalk kept his word and remained loyal to the Dunmore agreement. In the fall of 1777, he traveled to Point Pleasant to complain that Indian lands were being overrun by settlers, but for some reason he was immediately detained. On 9 November, a young white hunter was killed by an Indian and a mob broke down the cell door and killed Cornstalk and his companions. This was a tragic and inglorious end for a brilliant and courageous warrior chief that had been on a peace mission.

The ferocity, casualties, and results of the Revolutionary War overshadowed Dunmore’s War and the bitter Battle at Point Pleasant. It was, however, one of the many events that were inter-related and contributed to the peoples move toward rebellion and eventually to war and independence.

The Point Pleasant battlefield was neglected for nearly 70 years, but eventually the area was developed. The Tu-Endie-Wei Park (Shawnee for mingling of the waters) was established near the bridge that carries Route 35 across the Ohio River to Gallipolis, Ohio. The graves of the those killed there have been laid out in long rows beneath a bronze tablet recording their names. Nearby is Chief Cornstalk’s grave and a statue of a typical Virginia frontier rifleman. An 84-foot-tall granite shaft honoring all those who fought there towers over the site.

It is fitting that this park was established to honor all those who were engaged in brutal combat on that ground. Both sides are part of our heritage and contributed to our national development. This park rescued the memory of their bravery from the dustbin of history.