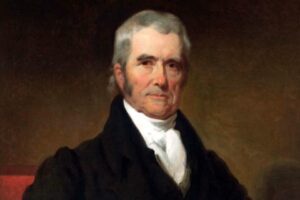

John Marshall was the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He established the court as the arbiter of all questions of constitutionality at all levels and the court’s role in the federal government. The Marshall court also confirmed the supremacy of the federal government and the federal Constitution over the states. He is regarded as the most influential justice to ever sit on the court which makes him one of the most influential to ever serve in our government.

The first of 15 children of Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith, John Marshall was born on 24 September 1755 in a log cabin in the frontier town of Germantown, Virginia (Near present day Midland). Thomas was employed by Lord Fairfax as a surveyor and land agent for Fauquier County, which provided a substantial income. Mary was descended from the powerful and wealthy Randolph family but was shunned by that family because her mother had eloped with a man the family believed was beneath her station in life.

John Marshall had little formal education. He was mostly home schooled by his father and was tutored by the Reverend James Thompson who resided with the Marshall family. He did spend one year at the Campbell Academy in Westmoreland County where he became friends with classmate and future president, James Madison. He was particularly influenced by his father who he credited with preparing him for the future. In later life he wrote the following: “to his care I am indebted for anything valuable which I may have acquired in my youth. He was my only intelligent companion; and was both a watchful parent and an affectionate friend.”

Thomas Marshall had served with George Washington during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Thomas and Washington were lifelong friends. Young John Marshall knew and admired Washington and was greatly influenced by him.

Thomas Marshall prospered and in 1773 completed construction of his estate known as Oak Hill. This estate is near Delaplane, Fauquier County, Virginia. It is still a working farm, and the beautiful original house is occupied.

After the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, Thomas and John Marshall both volunteered for military service. General Washington had encouraged 20-year-old John to volunteer, and he was commissioned lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Regiment. He proved to be a brave and talented young officer. John Marshall fought in several battles including Great Bridge, Brandywine, and Germantown. He was wounded at Germantown and endured the brutal winter at Valley Forge.

In 1780, John Marshall took leave to visit his father, Colonel Thomas Marshall at Yorktown. He met his future wife, Mary Willis Ambler while at Yorktown. John also left the military in 1780 to study law.

John Marshall attended a series of lectures by the famous Chancellor George Wythe at the College of William and Mary at Williamsburg, Virginia. These lectures only lasted about six weeks and were the only formal legal education that John Marshall ever received. However, he had quickly gained a firm understanding of the law.

Admission to the Virginia Bar also came in 1780, and John Marshall began his own legal practice. He built a successful practice mainly by defending clients against British creditors who were attempting to collect debts incurred before the Revolutionary War.

John Marshall married Mary “Polly” Ambler on 3 January 1783 in the home of her cousin, John Ambler. In 1790 the couple moved to a home they had built in Richmond, Virginia. They spent as much time as possible in this home where they could relax from the pressures of public life. In 1803, Marshall inherited Oak Hill when his father died, and they also spent private time there.

Concurrent with starting a legal practice, Marshall got involved in local and state politics. In 1782 he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for the first time. He was elected to this position again in 1787 and 1795. He rose rapidly in state politics due to his intelligence, charisma, and debating skills. In 1785 he became Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court where he presided over small criminal and civil court cases. In this position Marshall earned a reputation of fairness and clear communication.

In 1786 Marshall purchased the law practice of his cousin, Edmund Randolph who had been elected governor of Virginia. He practiced in Richmond and was widely known as a talented lawyer. He was quite successful taking on a wide array of important cases.

Marshall was also interested in national politics and recognized that the Articles of Confederation were inadequate for the country. Shays’ Rebellion reinforced his opinion. The Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania produced the new Constitution and submitted it to the states for ratification. Marshall was elected to the 1788 Virginia Ratifying Convention where he worked with James Madison to convince the delegates to ratify the document. After a long and contentious debate, Virginia ratified the Constitution by a vote of 89 to 79.

After the United States Government was established under the Constitution, newly elected President George Washington nominated Marshall to be US Attorney for Virginia. The nomination was confirmed by the Senate, but Marshall declined preferring to focus on his law practice.

When political parties were organized, Marshall identified with the Federalists and at the request of Alexander Hamilton organized the Federalists movement in Virginia to counter the influence of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party.

In 1795 President Washington asked Marshall to accept appointment as US Attorney General, but Marshall again declined. He did, however, serve in a variety of roles for the state of Virginia during this time.

Marshall argued a case (Ware v. Hylton) before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1796, but the court ruled against him. He did earn considerable admiration for the organization and delivery of his position.

Vice President John Adams, a Federalists, defeated Thomas Jefferson for the presidency in 1796. Adams wanted to continue the Washington policy of neutrality in the French Revolution, but the French began attacking American ships. Marshall was appointed to a three-member commission to negotiate with the French. The other members were Charles Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry. French Foreign Minister Talleyrand refused to negotiate with the delegation, and three of his agents demanded huge bribes to start serious negotiations. The Americans refused and left France.

When the facts about the French demands became public, Americans were incensed. The incident became popularly known as the “XYZ” Affair. In retaliation Congress imposed an embargo on French trade, and the “Quasi-War” with France began. Marshall supported most of the measures Congress adopted during the war, but he did oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts which were written to suppress dissent.

After his return from France, Marshall wanted to resume his private law practice, but George Washington convinced him to challenge a Democratic-Republican for the Thirteenth Virginia Congressional District seat. Marshall won in part because of the support of Patrick Henry. During the campaign, Marshall declined appointment to the US Supreme Court and President Adams appointed Bushrod Washington instead. Marshall took his seat when the sixth Congress convened in December 1799. He quickly emerged as a leader of moderate Federalists.

In May 1800, President Adams nominated Marshall to be Secretary of War, but changed his mind and nominated him as Secretary of State. Marshall was confirmed and took office on 6 June 1800. Marshall’s nomination had occurred because of a split between President Adams and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton led a Federalist faction that favored declaring war on France. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering was a Hamilton supporter and tried to undermine peace negotiations with France, so Adams had fired him and nominated Marshall.

Adams directed Marshall to find an end to the Quasi-War with France and to settle ongoing disputes with Britain, Spain, and the Barbary States. The Convention of 1800 ended the Quasi-War and reestablished trade with France and the situation with the Barbary States was settled by returning to earlier, although unsatisfactory agreements on 4 June 1805. Problems with Britain and Spain were not settled until the American victory in the War of 1812.

In those days, the office of Secretary of State included a wide range of domestic responsibilities, including deliverance of commissions of federal appointments and supervision of the construction of Washington, D.C. Obviously, the Secretary of State was a terribly busy man.

With the Federalists divided between Hamilton and Adams, the Democratic-Republicans swept the 1800 election. The vote ended in a tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, so the election was decided by the House of Representatives. Hamilton asked Marshall to support Jefferson, but he declined to support either candidate. Much to the anger of Burr, the House elected Jefferson President.

The Adams administration did not end until 4 March 1801 and Adams and the lame duck Congress passed the “Midnight Judges Act.” This act made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary including a reduction in justices of the Supreme Court from six to five. This was done to deny Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred.

In late 1800, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Oliver Ellsworth resigned due to poor health. Adams quickly nominated former Chief Justice John Jay, but Jay declined on 20 January 1801. With little time left before the Jefferson would take office, Marshall suggested that Adams elevate Associate Justice William Paterson, but Adams rejected this and appointed him instead.

There was considerable resistance to Marshall’s nomination in the Senate, but he was confirmed on 27 January 1801 and took office on 4 February. At the request of President Adams, Marshall also continued to serve as Secretary of State until Jefferson took office. John Adams later stated that “my gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.”

The Marshall Court convened for the first time on 2 February 1801 in the Supreme Court Chamber in the basement of the Capitol Building–the planners of Washington DC had forgotten to provide space for the Court. The Court consisted of Chief Justice Marshall and Associate Judges William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, Bushrod Washington, and Alfred Moore.

Since its establishment, the Court had been seen as relatively insignificant. It had issued only 63 decisions that had little impact, and it had never struck down a state or federal statute. Under the 34 years of John Marshall leadership, the Supreme Court became a powerful and important part of the federal government. Marshall himself was instrumental in shaping the nation’s understanding of constitutional law.

Marshall quickly changed the way the Court announced its decisions. Up to that time, each Justice authored a separate opinion (known as a “seriatim” opinion), which was confusing and weakened the authority of the Court. Marshall adopted the practice of handing down only a single majority opinion in order to present a clear ruling.

The Court met in Washington only two months a year—February and March. For six months the justices did circuit court duty in the states. When the Court was in session, the Justices boarded together in the same rooming house and avoided outside socializing. They discussed and argued each case intensely among themselves and usually made decisions in a matter of days. They Justices did not have clerks, so they had to listen closely to oral arguments and then introduce their opinions to the group to discuss and reach a majority ruling.

Chief Justice Marshall was a strong and charismatic leader who quickly recognized key points and was quite persuasive in debates. However, Marshall would listen to and consider all opinions preferring to reach decisions by consensus. After a decision was made, Marshall usually wrote the ruling himself. Since he was not widely read in the law, he seldom cited precedents. Instead, he often had Justice Joseph Story (a renowned legal scholar) locate the precedents and insert them.

During the 34-year-tenure of Marshall, the court would issue more than 1,000 decisions. Marshall personally wrote about half of the total, but he wrote two-thirds of those addressing constitutional questions.

Obviously, the court’s decisions covered a wide range of legal questions, but from what I have read most legal scholars have selected five as landmark cases that set groundbreaking precedent. I will point out the importance and precedence of these cases, but I am not competent to discuss the legal details.

“Marbury v. Madison” which reached the Supreme Court in 1803 was the first landmark case and established the Court’s right of judicial review (the ability to strike down state and federal laws based on constitutionality).

The case involved a dispute over President Jefferson’s refusal to allow Secretary of State Madison to deliver a commission authorized during the Adam’s administration. Politics were quite partisan, and Jefferson habitually pushed his perceived powers to, and past, the constitutional limits. The Court ruled that they had no power to force Jefferson to honor the commission, but they determined that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional. Based on this finding, the Court ruled that all laws conflicting with the Constitution should be rendered “null and void.”

Marbury v. Madison instituted the process of judicial review and positioned the Supreme Court as an equal partner with the legislative and executive branches. Today we accept this equality without question, but in 1803 governmental powers were still being sorted out by powerful and often jealous men.

“Fletcher v. Peck” came to the Supreme Court after the state of Georgia sold much of its frontier land to speculators in 1795. These buyers then resold the land to other speculators. There was a lot of bribery involved in these transactions which caused a public outcry. Georgia rescinded the sales and unsuccessfully tried to buy back the land at less than current value. President Jefferson tried to arrange for the Federal government to buy the land and compensate the investors, but the bill was defeated. The problem remained unresolved and reached the Marshall Court in1810.

In March, a unanimous decision of the Court voided Georgia’s rescinding of the original sales on the basis of the Contract Clause. This clause prohibits states from “impairing the obligations of contracts.” and they ruled the original sale of land was a contract. This case was important because it was the first time the Court ruled a state law unconstitutional, which further strengthened the Court’s standing.

“McCulloch v. Maryland” began in 1816 when Congress established the Second Bank of the United States to regulate the money supply and to provide loans. The state of Maryland imposed a tax on the bank’s branch in Baltimore, but the manager refused to pay. Maryland tried and convicted the manager, James McCulloch, who in 1819 appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court.

Maryland challenged the constitutionality of the bank and asserted it had the right to tax it. Marshall wrote the opinion which asserted that Congress had the power to charter the national bank and laid down the basic principle of “implied powers.” He wrote that the Constitution was “to endure for ages to come, and, consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs….” The Court also ruled that Maryland could not tax a national bank asserting that the power to tax is equivalent to “the power to destroy.”

Some legal scholars believe that the McCulloch v. Maryland was the most controversial decision made by the Marshall Court. Southerners attacked the decision as an overreach of federal power, but the principle of “implied powers” survived. In a subsequent case, “Osborn v. Bank of the United States,” the court ordered a state official to return seized funds to the bank and declared the Eleventh Amendment does not grant state officials “sovereign immunity” when they resist a federal court order.

“Cohens v. Virginia” came before the Court in 1821. The Cohen brothers had sold Washington D.C. lottery tickets in Virginia which violated Virginia state law. The brothers were convicted but appealed to the Supreme Court arguing that Congress had started the lottery, so they had a right to sell tickets in any state. The Marshall Court ruled in favor of Virginia and declared that the Supreme Court could review appeals from state courts that involved criminal law. This case is considered pivotal because it helped establish constitutional parameters for conflicting local and state laws.

“Gibbons v. Ogden” involved a monopoly granted to Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton in 1808 by the state of New York for the navigation of steamboats in state waters. The monopoly then granted a license to the partnership of Aaron Ogden and Thomas Gibbons to operate steamboats in New York waters. The partnership collapsed but Gibbons received a federal license allowing him to operate in the waters of any state. Ogden then won a judgment in state court that ordered Gibbons to cease operations in New York. Gibbons appealed to the Supreme Court in 1824.

Gibbons was represented by Congressman Daniel Webster and Attorney General William Wirt. They argued that Congress had exclusive power to regulate commerce while Ogden’s attorneys claimed the Constitution did not prohibit states from restricting navigation.

The Marshall Court ruled that navigation was a form of commerce and could be regulated by Congress. Further, since the monopoly conflicted with the federal license, the Court struck down the monopoly. The Supreme Court decision did not adopt Webster’s claim that Congress had the sole power to regulate commerce. This ruling was hailed in newspapers in all sections of the country as a blow against monopolies and the restraint of trade.

In 1829, Andrew Jackson was sworn in as President of the United States. Marshall was personally opposed to Jackson and had in fact criticized him during the campaign because he had attacked President John Q. Adams. President Jackson was a very direct and forceful man and he clashed with the Supreme Court often, particularly with regards to Jackson’s policy of Indian removal.

The Marshall Court had in 1823 established the supremacy of the federal government in dealing with Native American tribes. This supremacy was challenged by the state of Georgia during the 1830’s which caused a lot of legal activity. The case was eventually settled in favor of the federal government.

The Court also established that it had the power to hear appeals from state supreme courts when a federal issue was involved; that the protections of the Contract Clause applied to private corporations; and they upheld a state law that allowed individuals to file for bankruptcy. Marshall personally opposed the latter because he believed it violated the Contract Clause.

Volumes have been written about the Marshall Court’s decisions, but that type of analysis is beyond the scope of this article. There are, however, two incidents that Marshall was involved in that I believe reflect his character as a man.

The first was the 1804 impeachment of Associate Justice Samuel Chase by the House of Representatives. The House alleged that Chase had shown political bias in his judicial conduct. Many saw this as an attempt to intimidate federal judges appointed by an opposing political party. Marshall was a witness in the trial. He defended Chase and in March 1805 Chase was acquitted by a bipartisan Senate vote. Marshall’s reputation for honesty and legal knowledge was instrumental in obtaining bipartisan support for Chase. This case helped establish the independence of the Supreme Court from partisan politics.

The next incident was the trial of Aaron Burr. Burr had been Vice President in the first administration of Thomas Jefferson but was not renominated in the 1804 election. When his term ended in 1805, Burr traveled to the western frontier. He was planning to establish an independent country by overthrowing the Spanish in Texas. It was alleged that he also planned to illegally acquire territory from US states.

When the plot became known, President Jefferson demanded that Burr be arrested and charged with treason even though no warrant had been issued. Burr was arrested in 1807 and John Marshall presided over the trial. The only physical evidence against Burr was determined to be a forgery so there was no evidence to support the charge of treason and Burr was acquitted of all charges. Marshall had pointed out that thinking about a crime did not actually constitute a crime.

Marshall had been under intense pressure to convict Burr of treason, but he resisted and adhered to the law and legal precedence. President Jefferson was livid at the outcome of the trial and Marshall was viciously attacked by the president and the Democrat-Republican party. Marshall’s honorable resistance to politics further strengthened the independence of the judiciary.

After the death of Associate Justice Bushrod Washington in 1829, Marshall was the last original member of the Marshall Court and his influence declined as new justices joined the court. However, Marshall continued to preside over the court until his death in 1835.

In 1831, Marshall traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where he had surgery to remove “bladder stones.” His wife Polly died in December 1831 in Richmond. Their union had resulted in ten children, six who survived to adulthood. Between the births of a son in 1787 and a daughter in1795, Polly suffered two miscarriages and the death of two infants, which adversely affected her health for the rest of her life.

In early 1835, Marshall returned to Philadelphia for medical treatment, where he died on 6 July at the age of 79. The Liberty Bell was rung during his funeral procession to honor this giant of American history. Although not likely true, legend has it that this is when the bell cracked and never rung again. Marshall’s body was returned to Richmond and buried next to Polly in Shockoe Hill Cemetery.

John Marshall was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court for 34 years making him the longest serving Chief Justice in American history. The three Chief Justices that preceded him – John Jay, John Rutledge, and Oliver Ellsworth- had done little to enhance the role of the Court. It was a minor organ of the government when Marshall took over. Marshall and his Associate Justices issued more than 1,000 opinions and made the Court into a third co-equal branch of the US government. By his intellect and determination, Marshall gave the Court energy, weight, and dignity. He gave content to the Constitution’s omissions, clarified its ambiguities, and added breathtaking sweep to the powers it conferred.

Marshall Court decisions helped build a strong federal government and established the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of all questions of constitutionality with the power to overrule Congress, the President, the states, and all lower courts. The Marshall Court also defended the legal rights of corporations and shielded them from intrusive state governments. The Marshall Court firmly established the Constitution as the supreme law of the land and made the Court into what it is today.

John Marshall has been honored in many ways. The Library of Congress, the University of Virginia, and the College of William and Mary all have extensive collections of his papers. His image appeared on early currency and on postal stamps. A statue of Marshall stands on the ground floor of the Supreme Court Building, in the John Marshall Park in Washington D.C., and on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Numerous communities and counties are named for him. Many schools of all academic levels, including law schools, are named for him. A commemorative John Marshall dollar was minted in 2005.

I believe John Marshall has had more influence on the American government and on individual Americans than any other person in our history. In 1824 Senator Martin Van Buren, a political enemy, conceded that the Court attracted “idolatry” and its chief was admired “as the ablest judge now sitting upon any judicial bench in the world.” Quite high praise from an enemy! John Marshall was, and still is, a giant of American history and definitely was a super patriot and an American hero.