The 1772 burning of the HMS Gaspee was a significant, but lesser-known violent action in the lead-up to the American Revolution. It was perpetrated by prominent citizens of Rhode Island and was an act of open defiance against the authority of the British Crown. The event sharply increased tensions between colonials and the Crown. Tensions were already strained close to the breaking point because of the Boston Massacre that had occurred in 1770. The affair marked the first overt acts of violent uprising against Crown authority in British North America. It preceded the Boston Tea Party by more than a year and little Rhode Island pushed all 13 colonies closer to the coming war for independence.

The Gaspee Affair and other early defiant acts occurred in Narragansett Bay which should be described to set the scene. This bay is an inlet of the North Atlantic. It extends northward from Rhode Island Sound for 28 miles and almost divides Rhode Island into two parts. The bay is 3 to 12 miles wide. Several rivers empty into the bay, and it contains at least two large islands. Mount Hope Bay is a northeastern arm of the Narragansett. The Sakonnet River is a tidal strait that separates the island of Rhode from the mainland.

Narragansett Bay features deep water anchorage and includes at least two major ports-Providence and Newport. The bay is large enough for ships to maneuver and to anchor without blocking shipping lanes. The bay was, and still is, a major and active shipping center. During colonial days, it was vital to British and American traders and to the Royal Navy.

During much of the eighteenth century, Britain was at war. While at war, Britain did not want to antagonize its overseas colonies and risk the loss of vital and lucrative trade. Being somewhat ignored by the mother country, the colonists became more self-governing and much more independent.

The Rhode Island government was elected by the people, and they believed only their elected representatives could levy taxes on Rhode Island individuals and businesses. On the other hand, the British Parliament always believed they had the constitutional right to tax any English person or business anywhere in English colonies.

Following the global British victories over France in the 1756-1763 Seven Years War (French and Indian War in America), the British attempted to regain control over their colonies and to recoup the cost of the war. The Crown immediately antagonized all 13 colonies by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This proclamation prohibited all English colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains, which was unacceptable to the colonists. Many of them already had land claims in the west and the colonies were growing rapidly.

The British also believed that since the war had been partially fought to protect the colonies, it was only fair that the colonists help pay for it. The British also stationed about 10,000 troops in the American colonies for defense, and to keep their large standing army out of England. The main reason the British military was not demobilized after the war was that it would put about 1,500 politically well-connected officers out of work.

Parliament believed the colonists should be willing to pay taxes to help pay for garrisoning troops in the colonies. However, Britain had never before levied direct taxes on the colonies, and they greatly underestimated the resistance that would come from the Americans when they did.

Rhode Islanders increasingly resisted the British attempts to regain control of the colonies by new taxes such as the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend acts. Also, British rules and policies interfered with the colony’s traditional businesses. Many of these businesses were involved with the lucrative slave trade. Rhode Islanders were also convinced that the Sugar Act and Molasses Tax would adversely affect rum production and suppress their economy even more.

Even before major unrest began in Boston, Rhode Island was a hotbed of resistance and independent feeling, and they did not want to pay money into the British treasury. To avoid the duties on merchant ship’s cargo, smuggling became a way of life for Rhode Islanders. The British responded by increasing their enforcement of customs in all American ports. They also deputized Royal Navy officers to enforce the customs laws. Rhode Island law gave local sheriffs the authority to enforce civil law in the Narragansett Bay, so they believed the British military had no enforcement rights.

In 1763 the British purchased six Marblehead sloops and schooners, including the Gaspee, to bolster their duty enforcement. These ships were fast, armed with cannon, and small arms were available for the crew. The Admiralty deployed several of these ships to patrol the American coastline to inspect the cargos of American merchant ships. One of these Royal Navy ships, the six-gun HMS St. John, was stationed at the port of Newport in 1764.

Rhode Islanders had always disliked the British customs service and now the St John was increasing enforcement in Narragansett Bay. Enforcement also became more aggressive and more intrusive. The St John crew made matters worse by pressing locals into service and they were accused of stealing from local merchants. They were confronted by a local sheriff and other authorities, and the dispute became so heated that the captain of the St John decided to sail out of Newport waters for their safety.

As the St John was sailing away, the port’s defensive cannon crews were ordered to fire on her. They fired but the ship was out of range. There were no casualties during the incident, but this was the first time American guns had fired on a Royal Navy vessel. The colonists had shown that they were willing to risk war by physically standing up against British power.

Relations between all 13 colonies and Britain continued to deteriorate. In 1764, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which was strenuously opposed. Americans insisted the act violated their rights since they were not represented in Parliament.

Although the Stamp Act was rescinded in 1766, it was closely followed by another package of new taxes and regulations known as the Townshend Acts of 1767 and 1768. These acts were hated even more than the Stamp Act. American resistance stiffened and became more militant and, in most colonies, spawned the effective militant group, the Sons of Liberty. “No Taxation without representation” became the rallying call in all 13 colonies. The Sons of Liberty were organizing and leading protests and riots targeting the Townshend Acts, and they were also slowly developing the case for revolution.

To meet the increased resistance, the British reinforced their military presence trying to intimidate the locals. This allowed the British to confront even minor threats with overwhelming force. The overt resistance by the Americans and their obvious dislike of the troops caused the British troops to be nervous and they became even more aggressive trying to establish control.

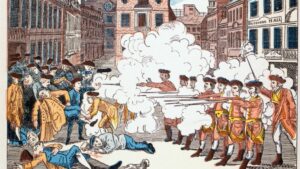

In October 1768, the British sent more troops to Boston, Massachusetts to “keep the peace.” All this did was increase tension and resistance and it boiled over on 5 March 1770. Colonists taunted a lone British sentry and became threatening. The soldier was reinforced, the situation deteriorated, and the nine British soldiers fired a volley into the crowd killing five colonists. The colonists named the incident the “Boston Massacre.”

News of the Boston Massacre, accompanied by an inflammatory and inaccurate depiction of the shooting by Paul Revere, traveled to all 13 colonies. Tension and unrest spiked throughout the colonies and the British troops became even more nervous. This was one more violent step on the road to open war and revolution.

Later in March, the HMS Gaspee sailed into Narragansett Bay and into an atmosphere of increased revolutionary fervor. The Gaspee was an 8-gun-schooner with a 19-man-crew. It was commanded by Royal Navy Lieutenant William Dudingston. Like the St John, Dudingston’s orders were to combat smuggling by inspecting the cargo of American merchant ships and by confiscating all contraband.

Dudingston soon gained a reputation for excessive enforcement that probably exceeded his authority. The Gaspee crew was boarding and detaining American ships without clear cause and confiscating their cargos. Since the British crew was allowed to keep a portion of what they confiscated, it appeared their actions were often motivated by greed rather than a sense of duty.

The Gaspee detained and boarded an American sloop, the Fortune, which was carrying undeclared barrels of rum. Lieutenant Dudingston ordered that the Fortune and its crew and cargo be sent to Boston where the Americans would be tried by a vice-admiralty court. The Rhode Island colonial authorities were enraged claiming Dudingston’s actions were illegal under the Rhode Island Royal Charter of 1663. The charter stated any arrest within the colony would be tried in the colony. Local resentment rose and a Rhode Island sheriff threatened to arrest Dudingston.

Dudingston consulted with his superior, Admiral John Montague who wrote an angry letter to the sheriff and Joseph Wanton, Governor of Rhode Island. Montague threatened to hang as a pirate anyone who tried to rescue any vessel confiscated by the Royal Navy. Wanton was not intimidated and responded with a defiant letter. He implied that Dudingston was the pirate and he informed Montague that the Admiralty had no right to give orders to colonial governors. He continued, “as to your advice not to send the sheriff onboard any boat of your squadron, please know that I will send the sheriff of this colony at any time, and to any place, within the body of it, as I see fit.”

The situation was already deteriorating, and this exchange did nothing to reduce tension. The arrogance of British authorities like Dudingston and Montague, was more than many colonists, particularly Rhode Islanders, could tolerate and some plotted to resolve the Gaspee “problem” on their own.

The opportunity came on 9 June 1772. The Gaspee was pursuing the packet ship, Hannah. (Packet ships were medium sized vessels used for international trade but had shallow enough draft to sail into rivers.) The Hannah sailed to shallow water and when the pursuing Gaspee entered the shallows at full sail, she ran aground near Warwick at a land point called Namquid Point (now known as Gaspee Point). The crew of the Hannah later claimed they intentionally lured Gaspee to the shallows.

No matter why it happened, the Gaspee was stuck tight, and the crew could not free her. Dudingston had no choice but to wait for high tide to free his ship.

The news about the predicament of the Gaspee reached Providence and a late-night meeting of the Sons of Liberty was held in a local tavern. They laid plans to take advantage of the situation by raiding the trapped ship. The raiding party was mostly made up of prominent citizens and was led by an influential merchant and Bristol County Sheriff named John Brown. A man identified as Captain Whipple was placed in command of the actual attack since he was an experienced sea captain who had engaged in naval combat. The Sons of Liberty members cast lead bullets before the raiding party boarded longboats with muffled oarlocks.

The raiders claimed they had eight or nine longboats and 64-100 men. Lieutenant Dudingston later made the ridiculous claim of dozens of longboats and over 250 colonists. The Gaspee deck could not have held anywhere near that number.

Brown’s raiders approached the Gaspee at about two AM on 10 June. They positioned their longboats to minimize any risk of cannon fire. They boarded the ship before the watch could sound the alarm and caught the sleeping crew by surprise. The crew’s weapons were locked away in a chest. Once on board, Brown assumed command, and the raiders claimed to have a warrant for Dudingston’s arrest. The ever-hot-headed Dudingston tried to resist and was shot in the groin by Joseph Bucklin who proclaimed when Dudingston fell, “I have killed the rascal.” This ended any thoughts the crew may have had about resisting and Dudingston surrendered the ship.

The shot had severed Dudingston’s femoral artery, which was usually fatal , and he was bleeding out fast. Doctor John Mawney was in the raiding party, and he applied a compression bandage to the wound which stopped the bleeding and saved Dudingston’s life.

The raiders took their time and read through the Gaspee’s papers. They arrested the crew, bound their hands, and loaded everyone into the longboats. They torched the ship and shoved off towards shore. They did hesitate for a short time to watch the Gaspee burn. The fire eventually reached the powder magazines, and a great explosion destroyed the hated Gaspee.

Once they reached shore, Brown’s raiders abandoned the Gaspee crew and returned to Providence. Dudingston tended his wound for the next few days but was then arrested by the sheriff and charged with “illegal seizure of cargo.”

Admiral Montague was livid over the loss of a Royal Navy ship to raiders, and he had to pay a big fine to free Dudingston. He then sent Dudingston to England to be court-martialed for the loss of the Gaspee.

Lieutenant Dudingston was in trouble because the British Admiralty believed there was never a legitimate reason to surrender a Royal Navy vessel. However, Dudingston was eventually acquitted and resumed his naval career. He later served in the American War for Independence and achieved the rank of admiral.

The Admiralty was outraged that a Royal Navy vessel was boarded and destroyed so easily. Montague launched an investigation to identify the raiders with the intention of sending them to England to be tried for treason. To avoid any action against colony authorities, Governor Wanton condemned the raid and “cooperated” with the investigation. He offered an anemic 100-pound reward for information leading to arrests. A very angry King George III offered a reward of 1,000 pounds, a fortune to ordinary citizens. The Gaspee had been purchased for only 545 pounds.

In January 1773, a commission was appointed by the King to investigate the incident, identify the raiders and try them for treason. Governor Wanton was placed in charge, and their first finding was that no Rhode Island civil officials were involved.

During months of interviews, only one alleged eyewitness was found. He was Aaron Briggs, an indentured servant of African and Indian descent who may have been a rower of one of the longboats. He supplied the names of five important merchants, including John Brown. Wanton doubted this testimony and questioned Briggs’ masters who claimed Briggs had been on their farm the night of 9-10 June. They testified he could not have witnessed the incident. The Briggs testimony was thrown out despite Montague believing him. Briggs felt threatened by those he named, so the British Navy supplied protection for him. No one was ever identified and charged for burning the Gaspee, nor for wounding Lieutenant Dudingston.

The identities of the raiders were not made public until after the Revolutionary War, even though they were well known by Rhode Islanders. Probably one of the best kept secrets in history.

Even though no Americans were punished for the Gaspee Affair, colonial leaders saw a threat in the investigation. The commission was granted authority to extradite those accused to England for trial. Witnesses and evidence would also be sent to England. This was a clear violation of colonist’s rights. They were guaranteed by their charter to be tried by a jury of their peers. Colonial newspapers reported this and purposely inflamed the political situation throughout the colonies.

Leaders in Virginia Colony, including Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry decided an organization was needed to protect American’s right to a fair trial. They created a permanent intercolonial committee of correspondence to coordinate responses to actions threatening American rights and liberties. Within a year every colony except Pennsylvania had formed a similar committee. The Gaspee Affair was uniting Americans in a common cause.

Eighteen months after the Gaspee Affair, the Boston Tea Party caused bigger political waves and is better known.

Even though the Gaspee Affair is not a well-known event, it was quite significant. It raised tensions between the Americans and the Crown when relations were already deteriorating. It also demonstrated that the British military was not invincible and could be challenged, even by civilians.

Americans had planned an armed raid on a Royal Navy vessel. They had forcefully boarded and then destroyed the ship, they had captured and detained the ship’s crew, and had purposely shot a British military officer. Earlier they had fired on the HMS St John.

When the details reached Britain, the Gaspee Affair was called “treason” and an “act of war” by Parliament and the King. No earlier incident had ever produced such a response by the British government.

The Americans did not yet recognize that they were at war, but the British realized that war had already started, and they began the necessary preparations to fight it. They began to assemble a large naval fleet and additional troops to reinforce their forces in North America. However, it was too late in 1774 to safely cross the Atlantic, so it was spring 1775 when these reinforcements set sail for America. The Battles of Lexington and Concord occurred in April 1775, so the British were correct in their assessment of the situation.

The American Revolutionary War was not precipitated by a single action or event. In the beginning, only a few Americans saw a need for separation from the mother country. Overreach by the Crown, and a long series of political and military confrontations accompanied by agitation from the committed separatists gradually convinced most of the people to revolt. Independence was finally won by ordinary people who were unified. They fought and died for a new concept of freedom from tyrants and government by and for the people.