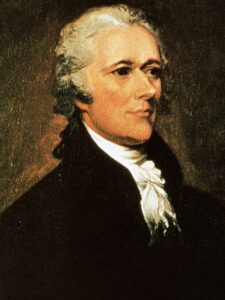

Alexander Hamilton was one of the most influential American founders. He was a statesman, politician, legal scholar, military officer, lawyer, banker, and economist. He was a staunch supporter and interpreter of the US Constitution. As the First Secretary of the Treasury, he basically founded the American financial system. He favored a strong federal government led by an active executive branch, strong commerce and industry, and a strong military. Hamilton contributed much and had a great future, but his highly partisan politics punctuated by an outspoken and polarizing presentation led to fierce opposition and was a major factor in the incidents that led to his early death in a duel with political foe, Aaron Burr.

Alexander Hamilton and his brother James Jr. Were born into obscurity and out of wedlock in Charlestown, Nevis in the Leeward Islands, which were then a part of the British West Indies. Their mother was Rachel Faucette, a married woman of British and French Huguenot descent. Their father was James A. Hamilton, a Scotsman who was the fourth son of Alexander Hamilton the laird of Orange in Ayrshire.

Rachel had been married to a Danish or German merchant, Johann Michael Lavien, on the Danish-owned Island of St. Croix. They had one son but in 1750 she left this family and moved to St. Kitts where she met James Hamilton. The couple then moved to Nevis where Rachel had inherited a building lot from her father.

Alexander listed his birth date as 11 January 1757 although there is some evidence that it was 1755. I believe 1757 is most likely because he said it was.

James Hamilton abandoned Rachel and the two boys, and she moved them to St. Croix. She supported the family by keeping a small store; however, she died on 19 February 1768 after contracting yellow fever. Rachel’s legal husband, Johann Lavien, seized her small estate in probate court but a friend bought the family’s books and gave them to Alexander. The Hamilton brothers were denied membership in the Church of England because their parents were not legally married.

Alexander became a clerk in a local import-export firm that traded with New York and New England. Both boys were briefly taken in by their cousin, Peter Lytton, but Lytton committed suicide in July 1769. He left his property to his mistress and their son. The Hamilton’s were again homeless, but James apprenticed with a carpenter, and Alexander was given a home by Nevis merchant Thomas Stevens.

Despite his youth, Alexander proved to be capable and reliable enough to be left in charge of the firm for five months while the owner was at sea. Hamilton was an avid reader and did some writing. In a letter to his father, he described a hurricane that had devastated Christiansted on 30 August 1772. His tutor and mentor, Hugh Knox, was so impressed by the letter that he submitted it for publication in the Royal Danish-American Gazette. Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow found the letter to be astounding that a self-educated clerk could write such a vivid description that also claim the hurricane was a “divine rebuke to human vanity and pomposity.” Community leaders were impressed enough to send Hamilton to the North American colonies for his education.

Alexander Hamilton arrived in Boston in October 1772 and proceeded to New York City where he obtained lodging with Hercules Mulligan. Mulligan’s brother was a trader and assisted Hamilton in selling cargo to finance his education. In 1773 Hamilton attended a preparatory school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. There he was influenced by a local intellectual and American revolutionary, William Livingston.

In the fall of 1773, Hamilton became a” private student” at King’s College (now Columbia) in New York City. His college roommate and lifelong friend, Robert Troup, noted Hamilton’s clarity and logic in presenting the patriot cause on 6 July 1774 at the Liberty Pole at King’s College. Hamilton had become a supporter of the American Revolutionary cause and when Samuel Seabury, a Church of England clergyman published pamphlets promoting the Loyalist cause, Hamilton responded anonymously with his first political writings.

Although he was a revolutionary, Hamilton did not approve of mob reprisals against Loyalists. He was credited with saving his college president and Loyalist, Myles Cooper, from an angry mob on 10 May 1775. It took courage to speak to and confront a mob while their target escaped.

After the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, Hamilton and other King’s College students joined a New York militia unit. Hamilton studied military history and tactics on his own and soon won promotion. He led a successful raid that captured British cannon while under fire from a British Ship. Possession of these cannon resulted in the unit becoming an artillery company in the Continental Army.

Through his connections with New York patriots Alexander McDougall and John Jay, Hamilton raised the New York Provincial Artillery Company and took part in the 1776 campaign around New York City. In the 3 January 1777 Battle of Princeton, actions by Hamilton and his artillery resulted in the capture of 194 British soldiers.

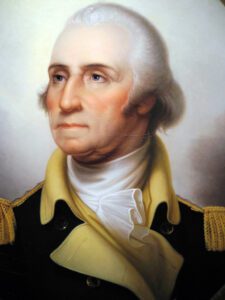

As his reputation grew, Hamilton was invited to serve as an aide by two generals, but he declined believing glory on the battlefield was the best avenue to improving his station in life. In March 1777 Hamilton received an invitation to serve as an aide to General Washington. He recognized a true opportunity and did not decline. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and served four years as Washington’s chief staff aide.

In his position, Hamilton handled correspondence with Congress, state governors, and powerful generals of the Continental Army. He drafted many of Washington’s orders and letters, and eventually issued Washington’s orders over his own signature. He was involved in a very wide range of duties as the General’s personal representative.

While serving in the military, Hamilton also managed to have a personal life. During the winter of 1779-1780 he was stationed in Morristown, New Jersey where he met Elizabeth Schuyler, a daughter of General Philip and Catherine Schuyler. Alexander and Elizabeth were married at the Schuyler Mansion in Albany, New York on 14 December 1780. The couple eventually had eight children who all lived to adulthood.

Hamilton always realized that combat command was his best avenue to improve his station in life. He could also see that the end of the war was getting nearer and his chances for battlefield glory were growing slimmer. He wanted a combat command, but Washington saw Hamilton as a valuable member of his staff and did not want to release him.

Washington was always under a great deal of pressure and sometimes was super-critical of his staff over minor situations. On 15 February 1781, Washington reprimanded Hamilton after an insignificant misunderstanding. As usual, Washington quickly tried to repair the situation, but Hamilton resigned from the staff. He officially departed in March and he and Elizabeth settled nearby.

Hamilton repeatedly requested a field command, but Washington refused citing the need to appoint men of higher rank. Finally in July 1781, Hamilton submitted a letter to the general that contained his commission, which suggested he would resign if he did not get a command.

Washington finally relented and assigned Hamilton commander of a New York battalion of light infantry and two Connecticut provisional companies.

In the spring of 1781, Washington and Lieutenant General Rochambeau decided to move the Northern Army south to Yorktown, Virginia to confront Lord Cornwallis who was encamped there. They managed to rapidly move the entire army arriving on 28 September. American and French engineers dug a series of parallel trenches in preparation for a major attack on the British position. The British were essentially trapped since French warships in the Chesapeake Bay blocked their only avenue of retreat.

American and French artillery began the preparatory artillery barrage on 9 October. The British, however, still maintained a narrow route for resupply and reinforcements which was protected by defensive Redoubts # 9 and # 10. These redoubts had to be taken to make the British position untenable.

French units were assigned to take Redoubt # 10, and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton with 400 light infantry was assigned to take Redoubt # 9. The attacks commenced on the night of 14 October with a diversionary attack on a different redoubt. The two primary attacking units advanced with bayonets fixed on unloaded muskets to maintain silence. Both encountered heavy resistance but after fierce close quarter fighting both redoubts were taken. These victories closed the gap and Cornwallis was surrounded and completely cut off from the outside. Cornwallis attempted a counterattack on 15 October, but it was a miserable failure.

On 17 October, a lone British drummer boy beating “parley” and one British officer with a white flag asked for a meeting. This officer began the initial negotiations for the surrender of Cornwallis’ 9,000-man army. The formal surrender occurred on 19 October 1781. (Cornwallis did not attend the formal surrender and had a subordinate surrender his sword.) This date is considered the de facto end of the War, although small actions continued for two more years until the Treaty of Paris was signed on 3 September 1783. The British forces then withdrew.

After his heroic actions at Yorktown, Hamilton returned to New York and resigned his commission in March 1782. He passed the bar in July and accepted an offer from Robert Morris to become receiver of Continental taxes for the state of New York. He was also appointed a New York representative to the Congress of the Confederation beginning in November 1782.

Hamilton had seen how ineffective the Confederation Congress was while on Washington’s staff, and he was openly critical. A series of unsuccessful attempts by Congress to improve the situation further demonstrated the impotence of the Confederation government.

Some opponents of the Confederation unwisely attempted to use discontent in the army to bring about changes. The army had not yet been disbanded and was posted at Newburgh, New York. It was in near mutiny over back pay and officer’s pensions. A military delegation had been sent to Congress in an attempt to resolve the situation but were turned down because Congress had no way of raising the funds. Obviously, the Army was not pleased about the situation. Several congressmen, including Hamilton, Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris tried to use the army to force changes. They suggested the army threaten Congress and that General Henry Knox defy civilian authority by not disbanding. They also tried to involve General Washington in this attempt to usurp civilian authority, but Washington warned them of the dangers of using the army as leverage against Congress.

This attempt certainly was not the American way. From the first, the military was supposed to be nonpolitical and to not interfere with the operation of the government. Fortunately, George Washington did decide to intervene but not in the way the plotters wanted. He addressed the officers personally and defused the whole situation.

The army disbanded in April 1783 and Congress tried to address the back pay situation but were again unsuccessful because the Articles of Confederation did not give them the power to raise funds. The military situation was not completely dead, however, because a group of disgruntled Pennsylvania soldiers marched on Philadelphia in June 1783 to demand their back pay. Although they caused the government to temporarily relocate to Princeton, New Jersey, the marchers were unsuccessful.

After all the confusion, Hamilton called for the Articles to be revised and suggested many features that were eventually incorporated in the Constitution. Hamilton resigned from Congress in 1783 and returned to New York City when the British withdrew from that city. He began practicing law with Richard Harison. They specialized in defending Tories and British subjects who claimed damages at the hand of Revolutionaries.

In 1784, Hamilton founded the Bank of New York, which is still in operation today. In addition, he was one of the men that restored King’s College as Columbia College. The college had been severely damaged during the war. He also attended the Annapolis Convention which resulted in a strong call for a constitutional convention.

In 1787, Hamilton served as assemblyman from New York County to the state legislature. His father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, chose him to be a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. New York governor, George Clinton, chose the other two delegates. They were both opposed to Hamilton’s stand for a strong central government, so the New York delegation always voted 2 to 1 against changes to the Articles.

Hamilton proposed having a president and senators elected for life, which caused other delegates to consider him to be a monarchist. Hamilton defended his position stating that impeachment would prevent any abuse of powers but some of his rhetoric sounded like a defense of monarchies. James Madison believed Hamilton was advocating for the “rich and well born” which essentially isolated Hamilton. Most delegates believed his ideas did not reflect the principles of the Revolution and liberty.

The final draft of the Constitution did not fully satisfy Hamilton, but he signed it because he believed it was a significant improvement over the Articles of Confederation. He also urged all other delegates to sign. He then took an active role in the successful campaign for the document’s ratification by New York in 1788. During that debate, a faction led by Governor Clinton wanted to amend the Constitution, but the Hamilton faction opposed any amendments. This became moot when enough states ratified the draft to make it the law of the land. Even so, the New York vote for ratification was quite close being 30 to 27.

In 1787 Hamilton had recruited John Jay and James Madison to write a series of essays to defend the proposed Constitution. We know these essays as The Federalist Papers, which were published using aliases. Hamilton’s alias was Publius. Eighty-five essays were published – Hamilton wrote 51, Madison 29, and Jay five. These essays are still studied by jurists and researchers to delve into the thinking and intentions of our founders when they drafted the Constitution.

As a member of the New York legislature, Hamilton was actively involved in the admission of Vermont into the union. This interesting saga began in 1764 when King George III ruled in favor of New York in a dispute between New York and New Hampshire over the region that became Vermont. As a result of the ruling, New York refused to recognize land grants that had been issued when the area had been a de facto part of New Hampshire. New York’s actions were strongly resisted by the inhabitants of the area. The Green Mountain Boys who gained fame during the Revolutionary War were originally raised to resist the colonial government of New York. By 1777 the residents of the disputed area declared they were a separate state called Vermont and by the next year had elected a state government.

Vermont was repeatedly denied representation in the Continental congress during the 1777 to 1785 period. Since they were rejected by Congress, they declared they were not a part of the United States. However, the peace treaty ending the Revolutionary War included Vermont by name with the other colonies. In 1784 Governor Clinton of New York actually asked Congress to declare war on Vermont, but Congress did not act.

By 1787 New York had given up plans to subjugate Vermont but still claimed jurisdiction. Hamilton had been arguing for recognition of Vermont against strong resistance and was in contact with Vermont’s attorney. Hamilton recognized that after the 1788 establishment of the United States, Vermont’s statehood could be considered with that of Kentucky.

Once the New York-Vermont border was established and New York made some financial compensation, Vermont was finally admitted to the Union in 1791.

Alexander Hamilton’s talents really began to shine when President George Washington appointed him the first Secretary of the Treasury on 11 September 1789. He served in that position until 31 January 1795. Most of the basic structure, responsibilities, and functions of the US Government were worked out during the Washington administration, and Hamilton had a major influence on the outcomes.

Hamilton developed his government position based on the British First Lord of the Treasury and equivalent to a prime minister. He acted as leader of the president’s cabinet and saw the treasury department and monetary policies as the primary key to strengthening and stabilizing the new government. Armed with this belief and his talents, he founded the stable financial system that we rely on today. Hamilton’s influence projected into other areas too because Washington relied on him and sought out his advice and assistance on many matters.

In September 1789 Congress requested that Hamilton submit a report on ways to improve the public credit. Hamilton and Robert Morris had long agreed that establishment of stable public credit was essential to achieving true independence. Besides his own extensive knowledge, Hamilton used French, British, and other American sources to prepare the report.

Hamilton, submitted that securities should be paid at the full value to their legitimate owners, including to those who purchased government bonds that most believed would never be valuable enough to redeem. He argued that liberty and security of property were inseparable and that government honoring contracts was the basis of public and private morality.

The Revolutionary War put the country into considerable debt. Hamilton divided debt into national and state, and the national debt was further divided into foreign and domestic. This division allowed treasury and Congress to address each one separately with the capability to apply unique solutions. Hamilton suggested combining state debt into the national debt and considering it all as federal debt. This suggestion was voted down by Congress.

Taxes on distilleries and land, and duties on imports were established to support the government and Hamilton proposed a method to eventually pay off the federal debt. Once Congress took up the national finances, the debate became ugly and political much like it does today.

Hamilton had long believed that a National Bank should be established and in 1790 he officially proposed that such a bank be chartered. He proposed the bank be capitalized with 10 million dollars and be governed by an appointed board of directors. The Madison proposal passed the Senate easily but ran into a buzzsaw in the House. Opponents argued that Hamilton was serving the interests of the Northeast and favoring the wealthy. James Madison argued that the bill was unconstitutional. The detractors were powerful and vocal but did not carry the day. The bill passed by a vote of 39 to 20 on 8 February 1791.

Opponents of the National Bank carried their arguments to President Washington trying to convince him to veto the bill. However, Washington signed the bill into law.

It should be pointed out that the proposed move of the government from New York City to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or to Virginia was complicating all legislation. Every politician and businessman had an opinion, and the outcome involved a lot of money and prestige.

Smuggling, pirating, and a lack of control of shipping in American waters had been a problem since before the Revolution and since had only gotten worse. Hamilton proposed that Congress establish a force of armed revenue cutters to patrol American waters and to assist custom collectors. Congress established the Revenue Cutter Service on 4 August 1790, which is considered the birth of the United States Coast Guard.

In 1791 Hamilton proposed the establishment of a National Mint. At the time, the US relied on Spanish currency. He proposed a dollar coin weighing nearly as much as the Spanish peso. He also proposed fractional coins based on decimals, such as 10 cent, one cent and half cent. This was a first and was because Hamilton wanted Americans of all economic classes to become accustomed to handling money.

There was wide political support for a mint and Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1792 establishing the United States Mint. Congress authorized a ten-dollar gold Eagle coin, a silver dollar, and fractional coins. The mint issued the first coins in 1795.

All governments must be financed which means TAXES. Americans had just fought a war that was largely about taxation. Taxes are never popular, and the American Whiskey Tax was resisted in rural areas where whiskey distilling was a cottage industry. Even though Hamilton and Congress tried to use tariffs to hold taxes down, the Whiskey distillers in western Pennsylvania and western Virginia were having none of it. Taxes were not being paid and tax collectors were being beaten and tarred and feathered.

The “Whiskey Rebellion” broke out in earnest in 1794 in Pennsylvania and Virginia. The government’s authority and prestige were at stake and this armed rebellion had to be put down, but without bloodshed if possible. President Washington personally took command, and along with General Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee assembled the largest number of troops ever in one place up to that time. This show of overwhelming force intimidated the leaders of the rebellion and ended it without bloodshed.

Early American politicians had very differing views of government. Some believed it would and should remain agrarian. Others, including Hamilton, wanted to develop manufacturing and industry to compete with Europe. Hamilton wanted government assistance for new industry by manipulation of protective duties and control of raw materials cost. He also wanted increased immigration to provide workers for new industry. Congress wisely shelved these contentious proposals without debate.

Hamilton did join a group that wanted to develop an industrial area in New Jersey at the Great Falls of the Passaic River. They founded the town of Patterson, which was named after the New Jersey governor. The effort never succeeded, and many investors went bankrupt. The head of the group died in debtor’s prison.

George Washington and many other early Americans were against the formation of political parties because they felt they would be too divisive. However, politicians were already divided by differing philosophies of government and it was only logical that they would organize. Thomas Jefferson and his followers formed the Democratic-Republican Party, usually known as the Republican Party. They favored strong individual states with government based in rural areas, which would be protected by state militias. They opposed banks, cities, and big centralized government.

Alexander Hamilton and his followers were known as Federalists, and they favored a strong central government supported by a national army and navy. They wanted government to be involved in business, industry, banking, cities, and some social programs. Today we would call Hamilton a “big government” politician. Hamilton supporters saw themselves as citizens that faithfully followed the United States Constitution.

The two parties were united in a vision of a dynamic and growing nation but obviously had quite different ideas on achieving these goals. The parties engaged in bitter rhetoric that was often very personal. They built national coalitions and established partisan newspapers. The newspapers engaged in personal attacks, major exaggerations, and invented claims (lies).

The two-party system exposed a major weakness in national elections procedures because the winner of the most votes became president, and the second vote getter became vice president. This could lead to the two offices being occupied by members of opposing parties, which did happen with devastating results and led directly to the death of Hamilton.

The American government had relations with the great European powers, but these relations were complicated by the wars and economies of those big countries. When Britain and France went to war in 1793, the US decided to remain neutral. The US wanted to engage in trade with all, especially Britain which was the most important trade partner. The French ambassador was kicked out of the US because he was recruiting mercenaries and privateers in the country.

To avoid war, President Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to Britain to negotiate with the British. Hamilton wrote most of Jay’s instructions. The negotiations resulted in Jay’s Treaty which was immediately and viciously attacked by the Republicans. However, Hamilton mobilized support throughout the country and the treaty was ratified in 1795. The treaty settled many problems remaining from the Revolutionary War and assured peace and free trade with the British for ten years.

Hamilton resigned from his office on 1 December 1794 because of his wife’s miscarriage and resulting frail health. Before his departure, he made several proposals concerning taxes and national debt, which Congress included in a bill that was debated about a month later. Hamilton resumed his law practice in New York to be close to his family. Hamilton also remained in contact with President Washington who sought his advice on many issues. He and James Madison both contributed ideas for Washington’s farewell address.

The election of 1796 saw Hamilton take a significant and questionable role. He tried to manipulate the electoral vote to elect Thomas Pinckney president and relegate John Adams to vice president again. His plan failed miserably, and Adams was elected president. His archenemy, Thomas Jefferson, became vice president. Hamilton’s machinations did not gain him any friends.

In 1797 Alexander Hamilton became the first major American politician to be involved in a sexual affair that became public. In 1791 he began an affair with Maria Reynolds who was “separated” from her husband. Maria had lured Hamilton into the affair, but Hamilton was a willing participant. However, the whole affair was a scam and Maria’s husband, James Reynolds, soon began blackmailing Hamilton. He paid about 1,300 dollars but continued the affair until he finally realized that Maria was in on the scam too. He then ended the affair.

The story became public after Maria’s husband and an accomplice were arrested on unrelated charges. The affair then became known to other politicians who confronted Hamilton. He provided evidence to them that his misconduct did not involve the treasury. In the summer of 1797, the affair was publicized, exaggerated, and sensationalized by journalist James Callender. Hamilton asked James Monroe, and Congressmen Muhlenberg, and Venable to publicly confirm that he had not compromised his position as Secretary of the Treasury. Monroe refused to comment and never forgave him. Hamilton then published a booklet that he called the “Reynolds Pamphlet” in which he discussed the affair in indelicate detail for the time. Hamilton was ridiculed but not destroyed, and his wife eventually forgave him.

During the 1798-1800 Quasi-War with France, Washington was recalled to command the army and he insisted that President Adams appoint Hamilton to the rank of major general. Washington made Hamilton the army’s senior major general which caused Henry Knox to decline appointment to serve as Hamilton’s junior. He had been senior to Hamilton during the Revolutionary War.

No land war materialized during the Quasi-War, so Washington remained at Mount Vernon and Hamilton was de facto commander of the Army. He wanted to take Spain’s North American colonies and proposed taxes to finance such a military campaign. New controversial taxes were passed, but Hamilton’s war plans never reached fruition. Peace brought an end to the need for a mobilized army and President Adams fired Secretary of State Pickering and Secretary of War McHenry when he discovered they were more loyal to Hamilton than to him.

The election of 1800 became a quagmire of political intrigue. Hamilton was again trying to manipulate the vote to achieve his personal goals. He worked against the Democratic-Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson, and Aaron Burr, but also opposed his party’s nominee, John Adams. Hamilton supported Adam’s running mate Charles C. Pinckney. Hamilton wrote a pamphlet that criticized Adams, which fell into Democratic-Republican hands, and they published it. This damaged Adams’ campaign and split the Federalist party, which assured a Democratic-Republican victory. It also destroyed Hamilton’s position among his party.

All of this resulted in an electoral vote tie of 73 votes for Jefferson and 73 for Burr, which meant the House of Representatives would select the winner. Hamilton actively campaigned against Burr even though he did not like Jefferson. He saw Jefferson as the lesser of two evils and claimed Burr was a “dangerous man” and a “mischievous enemy.” Sectional differences (North vs. South) were in play also. Jefferson was elected president and Burr became vice president. Jefferson did not trust nor like Burr and cut him out of his circle of advisors.

Jefferson would not support Burr for vice president in 1804 so Burr ran for New York Governor. Again, Hamilton opposed Burr and organized forces against him. They successfully defeated Burr, but a letter was made public that referred to several statements allegedly made by Hamilton that impugned Burr’s character and honesty. Burr viewed this as an attack on his honor and demanded a written apology from Hamilton. Hamilton claimed he did not remember making the statements so would not apologize and be viewed as a coward.

All efforts to reconcile the situation failed and a duel was arranged. Hamilton wrote that he would “throw away” his shot. Much has been written about this duel and how “honorable” Hamilton was, and I have read much of it. After studying several accounts, I have come to a different opinion.

The duel was at dawn on 11 July 1804 near Weehawken, New Jersey.

Some sources say that Hamilton provided the pistols and that they were heavier than normal dueling pistols. They also state that Hamilton had altered the pistols to have hair triggers. On the surface this does not appear to be especially important, but I believe this is evidence of skullduggery by Hamilton. First a heavier weapon would slightly slow the movement from a muzzle down position to the aiming position. From a muzzle up position, it would slightly speed the movement to lower it, which increases the possibility of passing the aiming point. Secondly, a hair trigger coupled with the increased weight would increase the possibility of a wild shot.

Nobody is sure of who fired first but it is known that Hamilton’s shot was over Burr’s head. If Hamilton fired first, he did not fire into the ground which was the protocol for throwing away a shot. I believe Hamilton fired first but his shot was wild because of the factors above. Burr then fired hitting Hamilton in the abdomen above the right hip. I do not believe Hamilton intended to throw away his shot. I think he became a victim of his own pistol changes which combined with the fact he was facing the sun (this position was stupidly selected by his seconds) resulted in the wild shot. I further believe that his claim to be planning to “throw away” his shot was a ruse to destroy Burr if he was killed. This part of his plan worked.

Burr’s shot was mortal, and Hamilton died the next day about 2 PM at a friend’s boarding house in Greenwich Village. He had suffered considerably and had been visited by family and friends. Gouverneur Morris gave the eulogy at Hamilton’s funeral, and he was buried in Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in Manhattan.

Hamilton’s widow, Elizabeth preserved his legacy by organizing his letter, papers, and other writings with the help of their son, John Church Hamilton. She also managed to get his biography published. Elizabeth wore a small package around her neck that contained pieces of a sonnet Alexander had written for her during their courtship.

The 11 July 1804 duel ended the life of one of the best financial minds in American history. His policies as Secretary of the Treasury significantly affected the US government and still influence it. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both believed Hamilton was unprincipled and dangerously aristocratic. His reputation has been mostly negative until recent years and he is now correctly considered a visionary. Being such a strong advocate for his Federalist beliefs of a strong federal government had made him the prime target of his opponents.

The duel also destroyed the career of Aaron Burr who had lots of potential to positively contribute to the country. He had shown his capabilities in organization, and his tenure as President of the Senate was groundbreaking.

Alexander Hamilton has been honored in many ways. Many Coast Guard and Naval vessels have been named for him. The 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery Regiment is nicknamed “Hamilton’s Own.” It is the oldest unit in the Regular Army and the only one to have served in the Revolutionary War. Hamilton is portrayed on the ten-dollar bill and US postal stamps. His alma mater, Columbia University has several memorials to him. Hamilton College is named for him. There are numerous buildings named for him, and there are numerous statues of Hamilton in many cities. Americans obviously recognize Hamilton’s contributions to our country and know he was a patriot and hero.