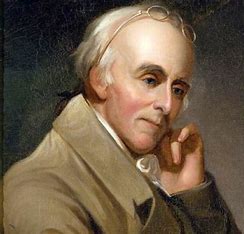

Benjamin Rush was an eminent physician, writer, educator, and humanitarian. He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and led Pennsylvania’s ratification of the United States Constitution. He opposed slavery, advocated for free public schools, for improved education for women, and for a more enlightened penal system. He was a professor of medical theory and clinical practice, but the quality of medicine he practiced was primitive even for the time. His early studies of mental disorders earned him the title of “father of American psychiatry.” He was the most well-known physician in America at the time of his death. He is also the most controversial

Benjamin Rush was the fourth of seven children born to John Rush and Susanna Hall. He was born in Byberry Township in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. John Rush was a farmer turned gunsmith who died in 1751 at the age of 39. Susanna then operated two successful stores to care for her family. When Benjamin was eight years old, he was sent to live in Maryland with his uncle, Samuel Finley. He and his older brother Jacob attended a school founded in 1744 by his uncle, which today is known as West Nottingham Academy.

In 1760, Benjamin earned a Bachelor of Arts Degree from the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and then apprenticed under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia until 1766. At Redman’s urging, Rush furthered his studies at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland where he earned an M.D. Degree in 1768.

Rush returned to Philadelphia in 1769 and opened a medical practice. He became a professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania), authored the first American chemistry textbook and several volumes on medical student education. He also published influential patriotic essays.

On 11 January 1776, Dr. Benjamin Rush married 17-year-old Julia Stockton. She was the daughter of his good friend Richard Stockton of Princeton, New Jersey. The officiating minister was Dr. John Witherspoon who he had helped bring to America ten years earlier. Six months later all three would sign the Declaration of Independence. Benjamin and Julia would have thirteen children with nine surviving the first year.

Rush was active in the Sons of Liberty and was elected to be a Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress in 1776. He signed the Declaration of Independence and later represented Philadelphia in the Pennsylvania legislature where he led the state’s successful effort to ratify the United States Constitution. In an 1811 letter to John Adams, Rush recounted the signing of the Declaration. In part, he described the “pensive and awful silence” as each man was called to sign what probably would be his death warrant.

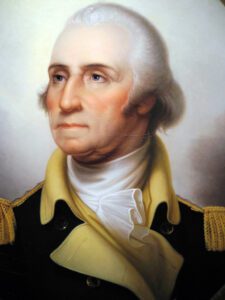

While still serving in the Continental Congress, Dr. Rush served as a medical officer with the Philadelphia militia and later as Surgeon-General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army. He treated the wounded in the field including at Trenton on Christmas Day of 1776 and at Princeton on 3 January 1777. He is depicted on the Trumbull painting The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777. Rush and Washington are depicted riding upon the scene as Mercer is killed. On the right of this painting British Captain William Leslie is shown mortally wounded. Leslie was a good friend of both Washington and Rush.

Julia Rush and other wives in Philadelphia went door-to-door to raise money for the army and soon raised a substantial sum of money. General Washington asked that the money be used for shirts for the troops. The women sewed 2,200 linen shirts and personalized each one with the name of the woman who made it. In tribute to his wife Benjamin Rush wrote: “Let me here bear testimony to the worth of this excellent woman. She fulfilled every duty as wife, and mother with fidelity and integrity. To me she was always a sincere and honest friend; had I yielded to her advice upon many occasions, I should have known less distress from various causes in my journey through life.”

Rush found the Army Medical Service to be in total disarray. Inadequate supplies, battle casualties, and remarkably high losses from typhoid, yellow fever and other camp illnesses were compounded by political conflicts between Dr. John Morgan and Dr. William Shippen, Jr.

Despite the problems, Rush accepted an appointment to the rank of Surgeon-General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army. He issued an order entitled Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers. The order was groundbreaking and became a foundation of preventative military medicine. It was repeatedly republished, including as late as 1908.

Rush also reported on Shippen’s misappropriation of supplies, alterations of official reports, and failure to visit hospitals. This put Rush in the center of a political firestorm.

The political situation was compounded by Rush writing letters to friends that were critical of General Washington and advocating for his removal from command. This occurred around the time of the Conway Cabal which was a serious effort to replace Washington. Washington learned of Rush’s letters and Shippen demanded Rush’s resignation. He received it early in 1778.

In an 1812 letter to John Adams, Rush expressed regret for his “gossip” against Washington and praised the general in glowing terms.

Back in civilian life, Rush was appointed to the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital in 1783 and served in that position until his death. He was appointed treasurer of the United States Mint in 1797 and served until 1813. In 1788 he became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was elected a foreign member of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences. He was also the founder of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Rush was beloved in Philadelphia where he set an example by caring for the poor. He became world famous for his dedication to duty during the city’s two great yellow fever epidemics that killed nearly 8,000. Rush himself had a severe case of yellow fever. He was honored for his contributions to medicine by medals and presents from the King of Prussia, Queen of Italy, and the Czar of Russia.

Rush became a professor of medical theory and clinical practice at the University of Pennsylvania in 1791 even though he personally performed the outdated techniques of bloodletting and purges for most illnesses. During the yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia, he treated patients with bleeding and purges, techniques that were ineffective at best and at worst were fatal. His medical practice began to diminish because of his continued use of those outdated treatments. Some claimed Rush’s bloodletting hastened the deaths of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington.

On a more positive note, Rush was one of the first to seriously study and to try to classify mental disorders. He also pioneered therapies for addictions and mental conditions. His report, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind was published in 1812.

Mental patients during Rush’s time were considered by many to be animals and were housed in appalling conditions. Treatment included physical restraint, chains, and bloodletting. In 1792 Rush led a successful campaign for the state to build facilities where mental patients could be housed in more humane conditions. Because of his early work, in 1965, the American Psychiatric Association designated Rush the father of American Psychiatry.

Benjamin Rush was a serious social warrior championing many causes. He fought hard for temperance and was a founding member of the “Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons.” This organization is still active today under the name “Pennsylvania Prison Society.” The group has been responsible for many changes, some good and some bad, over the years. Their efforts certainly brought about improved inmate living conditions. They also greatly influenced the unique design and construction of Eastern State Penitentiary, which operated from 1829 to 1971 in Philadelphia.

Capital Punishment and criminal punishment in general were subjects that Rush felt strongly about. He pushed the state of Pennsylvania to build the first state penitentiary, the Walnut Street Prison, in 1790. He believed that public punishment, such as placing the person in stocks, which was common at the time, was counterproductive. He proposed private confinement, labor, solitude, and religious instruction. Eastern State Penitentiary was originally designed to put most of Rush’s ideas into practice.

Rush was totally against the death penalty. His outspoken opposition to capital punishment caused the Pennsylvania legislature in 1794 to abolish the death penalty except for first-degree murder. The death penalty was later reinstated and continues to be controversial today.

Rush opposed slavery his entire life on both moral and scientific principles. Being a prominent physician and respected college professor, he was a strong voice against the “evils of slavery.” He authored many articles that attacked the slave trade and the institution of slavery at a time when many hesitated to speak up.

Public education in Pennsylvania was actively promoted by Rush. He wanted children to receive at least a basic education at tax-supported free schools because he believed citizens needed knowledge to protect their rights. Despite his efforts, Pennsylvania had no state-wide system of free schools until the 1830s.

During Rush’s time, men saw little need for educating women. However, after the Revolution, Rush proposed that “elite” women be educated in language, vocal music, dancing, sciences, bookkeeping, history, and moral philosophy. He saw little need for women to be educated in the more advanced sciences or mathematics and he opposed coed classes. He was instrumental in the founding of the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia, the first chartered women’s institution of higher learning in the city.

This concept of education of elite women grew dramatically as women demanded a role in creating the Republic. Since it was generally accepted that a woman’s principal role was to bear children, the image of ideal Republican motherhood emerged. Women were to teach the young about religion, patriotism, the blessings of liberty, and the true meaning of Republicanism. This made women responsible for the continuity of a stable society.

Rush was a deeply religious man although his religious views were as complicated as the rest of his life. He certainly did not believe in the separation of church and state. He proposed that government require the use of the Holy Bible in schools and that the government furnish every American family with a Bible. He advocated for Bible quotes to be placed over the entrances of all government buildings. Rush believed the United States was the work of God, that men alone could not have authored the founding documents.

Benjamin Rush died on 19 April 1813 of typhus fever. True to his treatment of his patients, he insisted on being treated by bloodletting. He is buried in the Christ Church Burial Gound in Philadelphia. Julia was buried next to him thirty years later. Benjamin Rush’s gravestone inscription includes the following Biblical quote: “Well done good and faithful servant enter into the joy of the Lord.”

A statue of Benjamin Rush is located near the US Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery building on the grounds of the old Naval Observatory in Washington, DC. A replica is located at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He has also been honored by having schools, an Indiana County and town, and a state park in Philadelphia named after him. The American Psychiatric Assocation honored him as mentioned earlier.

I have researched Benjamin Rush more than most of my subjects because he was so famous and admired, but he was also a man of considerable contradictions. He obviously was brilliant, a patriot, an educator, and an advocate for many good changes in society. He educated over 3,000 medical students including many who achieved fame for their excellence. Some of his students established the Rush Medical College in Chicago in his honor.

Despite being in the forefront of medical education, Rush continued to use outdated and dangerous methods that were often lethal in his own practice. He was apparently a difficult man to deal with because of his huge ego. He was a notorious gossip, and his severe flaws blemish his otherwise outstanding life. I am going to conclude with a few quotes from some of my sources:

English journalist and politician William Cobbett accused Rush of “killing more patients than he helped” by using bloodletting and purges.

When John Adams first met Rush he wrote: “An elegant, ingenious body, a sprightly, pretty fellow,” and “Too much of a talker to be a deep thinker, elegant, not great.”

Later Adams wrote: Rush “was handsome, well-spoken, a gentleman and a very attractive figure—he was also a gossip and was quick to rush to judgement about others. He was supremely confident of his own opinion and decisions, yet shallow and very unscientific in practice.”

When Rush died, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Adams: “a better man than Rush could not have left us, more benevolent, more learned, of finer genius, or more honest.”

Adams replied: “I know of no character living or dead, who has done more real good in America.”

Adams wrote Julia Rush: “there is no one outside my own family whose friendship was so essential to my happiness.”

Portion of the Conclusion from an essay authored by Robert L. North, M. D. Published by Baylor University Medical Center 13 January 2000:

“Benjamin Rush has been hailed as “the American Sydenham,” “the Pennsylvania Hippocrates,” the “father of modern psychiatry,” and the founder of American medicine. The American Medical Association erected a statue of him in Washington, DC, the only physician so honored. A medical school is named after him. He was a prolific and facile writer and a very influential teacher. Yet, the only enduring mark he has left on the history of American medicine is his embarrassing, obdurate, messianic insistence, in the face of all factual evidence to the contrary, on the curative powers of heroic depletion therapy.”