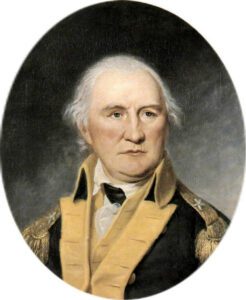

Nathanael Greene is another self-educated American military leader and is considered second only to George Washington. In 1780 he was given command of the southern theater of operations where he combined highly effective guerilla warfare with traditional operations and turned the tide of the Revolutionary War. His tactics led to the British retreat to Yorktown, Virginia where Cornwallis was trapped by Washington and eventually surrendered. Unfortunately, Greene died shortly after his retirement from the army, at the age of 43, which denied the new nation of his many talents.

Nathanael (this is the correct spelling) Greene was born on 7 August 1741 on a farm in Warwick Township, Rhode Island to Mary Mott and Nathanael Greene, Sr. His father was a prosperous Quaker merchant and farmer. He had two older half-brothers from his father’s first marriage and was one of six children born to Mary and Nathanael, Sr. At some point during his childhood, Greene Jr. developed a slight limp that lasted the rest of his life.

Because of his religious beliefs, Nathaneal, Sr. did not believe in book learning, dancing, or other frivolous activities. Despite this, Nathaneal, Jr was able to convince his father to hire a tutor for him. He studied mathematics, the classics, law, and works on the Age of Enlightenment.

In 1770, Greene, Jr. moved to Coventry, Rhode Island to take charge of the family-owned foundry. He built a house in Coventry named Speil Hall. Later in 1770, he and his brothers inherited the entire family estate following the death of their father. Greene Jr. used part of his inheritance to assemble a large library that included classic military commentaries by Caesar, Frederick the Great, and Maurice de Saxe.

Greene married 19-year-old Catherine Littlefield in July 1774. She was a niece-by-marriage of his distant cousin, William Greene. William was an influential political leader in Rhode Island. One of his younger brothers married a daughter of Samuel Ward another important Rhode Island politician. Ward became an important ally of Nathaneal until his death in 1776.

Parliament’s actions following the French and Indian War (!754-1763) began the events that eventually led to Revolution. The war had been expensive and the cost of maintaining a military presence to protect the colonies caused the Parliament to begin imposing new taxes on the colonies to recover some of that cost.

The taxes were not particularly unreasonable since the colonists had played a role in instigating the war and the British military maintained a deterrent force to protect the colonies. However, Parliament did not let the colonists have any input on their deliberations and just assumed the colonists would not seriously object to their edicts. They were very wrong.

The resistance was made more personal to Greene by British Navy Lieutenant William Dudington commanding HMS Gaspee. The Gaspee was enforcing the hated Navigation Acts in Narragansett Bay when it seized a vessel owned by the Greene brothers. Nathaneal sued Dudington for damages. The lawsuit was ultimately successful but while it was pending, Dudington’s vessel was torched by a group of Rhode Island men on 9 June 1772. This became known as the Gaspee Affair.

During this time, Greene’s life began to change. He drifted away from the Quaker Faith and was suspended from Quaker meetings. After Parliament’s 1774 passage of taxes that colonials dubbed the “Intolerable Acts,” he helped organize a local militia known as the Kentish Guards. Because of his limp, he was not selected to be an officer.

The War for American Independence began in April 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. In May the Rhode Island legislature established the Rhode Island Army of Observation and selected Nathanael Greene to command it. Greene’s army deployed to Boston where colonial forces had laid siege to the British garrison. Greene missed the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill because he was in Rhode Island.

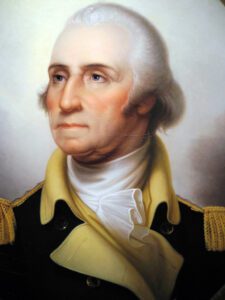

Also in June, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army and gave George Washington command of all colonial forces. His title was stated to be “General and Commander in Chief.” Washington wore three stars but there were no Lieutenant Generals in the Continental Army, and Washington was referred to simply as “General.” Congress also appointed 16 other generals, including Nathanael Greene commissioned to the rank of brigadier general.

General Washington took command at Boston in July. He organized his army into three divisions, each consisting of two brigades made up of regiments from different colonies. Greene was given command of a brigade of seven regiments.

The siege of Boston continued until March 1776 when the British were forced out of the city. Greene briefly served as commander of colonial forces in Boston, but he rejoined Washington in April 1776.

The New York and New Jersey Campaign began after the Boston siege and Washington established his headquarters in Manhattan. Greene was assigned to prepare for the expected invasion of Long Island, and he concentrated on building up fortifications in Brooklyn. Greene also befriended Colonel Henry Knox who had transported cannon from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston. These cannon were used to force the British out of Boston. During this time Greene and several others were promoted to major general (MG).

The Battle of Long Island, which was the first British move to capture New York City, began on 22 August 1776 when Major General Lord William Howe landed on Long Island and engaged Greene’s units. Greene, however, was not commanding due to illness and MG Israel Putnam had replaced him. Putnam deployed his forces poorly. Howe flanked the Continentals and attacked them from the rear. Some units bravely fought rearguard actions but were overwhelmed and routed.

Howe delayed two days to prepare his final assault. When he lost his naval support due to a storm, Washington’s forces successfully retreated across the East River to Manhattan.

Greene urged Washington to burn the city to keep it from falling into British hands, but Congress forbade this. Washington then wanted to fortify the city but his officers, including Greene, convinced him the city could not be defended. Washington withdrew to Harlem Heights as the British continued to move forward.

A British reconnaissance move on 16 September resulted in a counterattack by the Continentals. The two armies stood and exchanged fire until the British began to run low on ammunition and began a slow retreat. The Continentals pressed their advantage, but Washington withdrew them fearing a trap. The Battle of Harlem Heights was a minor British defeat but was one of the first Continental victories of the war and raised morale.

Following the Battle of Harlem Heights, Washington placed Greene in command of both Fort Constitution (later Fort Lee) on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River and Fort Washington on the other side of the river. Later, Washington suggested Greene abandon Fort Washington because it was vulnerable to attack, but Greene convinced Washington to continue occupation of the fort. In November 1776, the British attacked the fort capturing it and the 3,000-man garrison. Greene was criticized severely by Congress, but Washington declined to relieve him.

Shortly after the Battle of Fort Washington, Major General Lord Cornwallis captured Fort Lee and the Continental Army retreated across New Jersey into Pennsylvania.

In a daring and exceedingly difficult maneuver, General Washington’s army crossed the icy and treacherous Delaware River on Christmas Day 1776 and won two crucial battles. In the battle of Trenton, the Americans defeated a formidable garrison of Hessian mercenaries before withdrawing. MG Greene commanded one of the flanking units in this battle while Colonel Knox’s artillery bombarded the Hessians. The units than converged on the garrison rapidly defeating the Hessians.

A week later the Americans moved on Trenton again to draw the British south. Lord Cornwallis moved south to confront Washington. He engaged Washington but did not defeat him by the end of the day. Cornwallis relaxed because he believed he had Washington trapped. He was wrong. Washington tricked him into thinking he was still in camp while he made a daring night march to capture Princeton on 3 January.

The Battle of Princeton opened when a British bayonet charge broke Brigadier General (BG) Hugh Mercer’s lines. Mercer was killed trying to rally his troops. General Washington bravely rode between the firing lines, rallied the Americans, and drove the British back. He then pursued the retreating British. The battle moved into Princeton where 200 British regulars were defending a stout stone building. Continental cannon fire caused the British to surrender ending the Battle of Princeton.

Washington then withdrew back across the Delaware and moved into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey.

As a result of these two battles, the Americans gained control of much of New Jersey. More importantly, the morale and unity of the army was improved at a critical time.

The quarters at Morristown permitted Washinton to keep track of the British who were wintering in New York City and to be able to react if the British moved. The Winter of 1776-1777 was cold, supplies were scarce, and the army began to shrink. Some soldiers deserted, and others refused to reenlist. Fortunately, Washington’s growing popularity helped attract new recruits who he molded into better and more disciplined soldiers. He also made promises of land and cash bounties which came back to haunt the army later. When fighting resumed Washington’s immediate command numbered 11,000 with another 17,000 in New York.

The army was at Morristown for the first half of 1777. Meanwhile, the British launched a campaign to capture Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the seat of American government.

General Washington was determined to prevent the capture of Philadelphia so on 11 September 1777 he took up positions along Brandywine Creek. He mistakenly believed that he had blocked all fords across the Brandywine.

Opposing Washington was Sir William Howe and an army of 15,500 British Regulars and Hessians. Covered by heavy fog, the British moved into position. The Hessians were ordered to demonstrate at Chadds Ford while the bulk of Howe’s forces crossed the Brandywine farther upstream.

The battle had been raging for hours by the time Howe’s force appeared undetected on the Continental right flank. Washington dispatched troops to shore up his flank. They put up a stiff resistance but were eventually overrun by Howe’s men. Simultaneously, the Hessians hit the Americans near the Quaker meeting house at Chadds Ford. Washington’s lines collapsed.

To prevent the defeat turning into disaster Washington ordered General Greene’s division to act as a rear-guard while the army escaped to the northeast. Greene’s men counterattacked, going toe-to-toe with the British. When night fell, the Americans fell back in an orderly retreat, led in part by the wounded MG Marquis de Lafayette.

The defeat allowed the British to occupy Philadelphia, but the bulk of the Continental army survived to fight another day. The Continental Congress moved to York, Pennsylvania.

After taking the American Capitol, General Howe deployed two brigades of regulars and a contingent of Hessians to the village of Germantown. They totaled about 9,000 men. General Washington decided to attack and destroy this force using a double envelopment with a force of 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militia.

Washington set his plan into motion on the night of 3 October by dividing his army to attack the British from multiple directions at dawn. MG John Sullivan was to attack with the main force while General Greene was to attack the flank. The militia, under MG William Smallwood, was to strike the extreme right and rear. Unfortunately for Washington, darkness and a heavy fog delayed the advance and cost him the element of surprise.

Sullivan’s column was the first to make contact, driving back the British pickets. The British were surprised by the Americans, and some were cut off from the main body. One hundred twenty British troops took shelter in the large stone house known as Cliveden. This fortified position was a thorn in the Americans’ side for the remainder of the battle, with numerous assaults being repulsed with heavy casualties. Sullivan also pushed his men towards the British center.

On the left, one of Sullivan’s divisions, commanded by BG “Mad” Anthony Wayne, became separated in the fog. To make matters worse, Sullivan’s men were beginning to run low on ammunition, causing their fire to slacken. The separation, combined with the lack of fire from their comrades and the commotion of the attack on Cliveden behind them, convinced Wayne’s men that they were cut off, causing them to withdraw.

Fortunately, Greene arrived in time to strike the British before Wayne could be routed. Only the steadiness and grit of Greene’s and Wayne’s men and the American artillery prevented a total disaster. The American retreat was also aided by the onset of darkness.

Despite the Battle of Germantown being a British victory, many Europeans, especially the French, were impressed by the determination of the Continental Army.

In December, the Army established 1777-1778 winter quarters at Valley Forge, 25 miles northwest of Philadelphia. During the winter, General Greene clashed with Thomas Mifflin and other members of the Conway Cabal, which was a group that sought to replace General George Washington with MG Horatio Gates. Their cause failed but not before creating a distraction that the army did not need.

In March 1778 Greene reluctantly accepted the position of Quartermaster General like a good soldier and set out to do it to the best of his ability. He and his top assistants reorganized his 3,000-person department and established supply depots in strategic places around the country. Although he was a staff officer, Greene continued to attend Washington’s councils-of-war.

After France allied with America and joined the war in early 1778, the British commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton withdrew from Philadelphia and started moving to New York. Generals Wayne, Lafayette, and Greene recommended to Washington that they attack the British while they moved through New Jersey and Washington agreed.

On 28 June, Washington and his lead units caught up with the rear guard of the British army near Monmouth, New Jersey. The rear guard was commanded by Lord Cornwallis. MG Charles Lee with a superior force was ordered to attack the British. His men had undergone extensive training during the winter, but Lee lacked confidence in them and did not press his advantage. He ceded the advantage to the British who counterattacked routing the Americans.

Fleeing, panicked troops met Washinton as he approached the fighting. Enraged, he galloped ahead and angrily took command and rallied the troops to continue the assault. This delaying action gave enough time for the rest of the army to move up.

Washington placed Greene’s division on the right and Major General Stirling’s division on the left. Lee’s men were turned over to Lafayette and were kept in reserve. Wayne took command of the rest of Lee’s men and occupied Lafayette’s front. Artillery was stationed on both flanks. The fighting was bitter and see-sawed back and forth in the brutal heat for hours. About 6:00 PM the British were exhausted and disengaged. Wayne wanted to press the attack, but Washington believed the men were spent.

Rather than renewing the fight the next day, Cornwallis slipped away during the night. He gained a day’s march on Washington, and he resumed his move north.

In July Greene took leave to take part in an attack on the British in Rhode Island. The subsequent battle resulted in the British retreating from the state and Greene resumed his duties as quartermaster general.

In June 1780 British forces attempted an invasion of New Jersey. Originating in Staten Island and marching through Elizabethtown, New Jersey, they intended to capture the strategic Hobart Gap. This would enable them to march on American headquarters in Morristown.

The Americans decided to take a stand in the small village of Springfield where General Greene assumed command.

On 23 June, the British approached in two columns, but General Greene was advantageously positioned. The British force, about 5,000-men strong, with cavalry and almost 20 cannon, seemed sufficient to crush any American army that might oppose them. However, for more than 40 minutes, the Americans fought five times their number to a standstill. The British began to slowly push them back but were unable to breach the American line, so they resorted to burning and looting. After setting fire to Springfield, they retreated to the shore, and crossed over in haste from Elizabethtown to Staten Island.

The British had lost a rare opportunity for the conquest of New Jersey, and possibly the destruction or dispersion of Washington’s army. Greene’s men had performed gallantly and saved the day.

Greene resigned his quartermaster job in a letter that also criticized Congress. Some members of Congress wanted Greene’s commission revoked but Washington intervened and saved Greene’s position in the Continental army.

After General Benedict Arnold defected to the British in September 1780, Greene briefly served as commandant of West Point. He presided over the hanging of John Andre in October 1780. Andre had been Arnold’s contact in the British army.

By mid-1778, the war in the north had reached a stalemate. The British remained in New York City and Washington was positioned nearby on the Hudson River. France was entering the war, and King George III was demanding that the British army quickly subdue the colonies. Consequently, the British saw the south as their path to victory. There were fewer trained Continental troops in the south, there were many Loyalist militias, and they believed there was little popular support for the war.

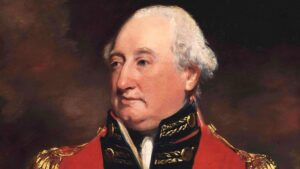

The British occupied Savannah, Georgia in late 1778, Charleston, South Carolina in May 1779, and they engaged the Americans near Camden, South Carolina on 16 August 1780. The Americans were under the command of Major General Horatio Gates and the British were commanded by Lord Cornwallis. The Americans greatly outnumbered the British but were routed and humiliated.

The Battle of Camden was the worse American defeat of the Revolutionary War. There were pockets of Americans who bravely stood their ground, but the “retreat” was a torrent of desertions and looting. According to American Colonel Otto Williams, MG Gates, and MG Richard Caswell (later governor of North Carolina) were on horseback and ahead of all other deserters. The two generals fled non-stop about 60 miles to Charlotte, North Carolina.

On 14 October 1780 Washington gave command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army to General Greene. Greene assumed command in December. He faced a 6,000-man British army commanded by Lord Cornwallis. The British force included cavalry commanded by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, and many Loyalist militia. Tarleton was intensely hated by the colonials for his brutal treatment of military prisoners and civilians.

Outnumbered and undersupplied, Greene wisely chose a strategy of “conservation of forces” by not committing his main force units unless victory was likely. He relied on his guerrilla forces to keep the enemy off balance and to provide him with intelligence. This was the perfect tactic since his army was inferior in numbers to the well organized and experienced British. However, the British had a long supply line, which was vulnerable to guerrilla attack, and the population was more loyal to the rebels than the British expected.

Greene’s key subordinates were his second-in-command professional soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, brilliant cavalry commander Lieutenant Colonel Henry (Light Horse Harry) Lee, Major General Marquis de Lafayette, Brigadier General Daniel Morgan (Morgans Rifles), and Brigadier General Francis (Swamp Fox) Marion. This was an incredibly skilled group of officers that were perfect for the type of war they would wage against the British.

Morgan was a frontiersman, pioneer, and politician from Virginia. He fought in the French and Indian War. He was one of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the Revolutionary War who often used non-conventional tactics. He commanded the famous “Morgan’s Riflemen.”

Francis Marion was a South Carolina planter who had fought in the French and Indian War. During that war he learned the Cherokee way of fighting and applied that knowledge to the tactics that earned him the name “Swamp Fox.” Marion and his guerilla force were instrumental in winning the war in the south. They gathered actionable intelligence and kept the British off-balance making them split their forces to try to find and defeat them.

Before Greene assumed command, loyalist and rebel militias clashed in October at Kings Mountain, South Carolina. The battle was a rebel victory, which delayed Cornwallis’ planned advance into North Carolina.

Greene went against conventional military wisdom by dividing his forces when facing a superior enemy. He led the main American force southeast while Morgan led a smaller force to the southwest. Cornwallis responded by dividing his forces marching the main detachment against Greene while Tarleton led a contingent against Morgan.

In the January1781 Battle of Cowpens, Morgan nearly destroyed Tarleton’s force. Tarleton narrowly escaped with only about 200 men. Following the battle, Cornwallis pursued Morgan, burning some of his own supplies to speed up his army’s pace. Greene then linked up with Morgan and moved into North Carolina to pull Cornwallis farther away from his supply lines.

On 9 February, Greene and his officers decided to continue north to the Dan River on the North Carolina-Virginia border. With the British in close pursuit, Greene again divided his force. He led the main detachment north while sending a small force to harass the pursuing British. Greene crossed the Dan on 14 February, but Cornwallis refused to move any farther from his supply line and turned south to Hillsborough, North Carolina. Greene recrossed the Dan on 22 February.

Greene continued harassing Cornwallis. In early March he received reinforcements from North Carolina and Virginia doubling his numbers to about 4,000 men. On 14 March Greene moved to Guilford Courthouse and began preparing for an attack by Cornwallis. He established three defensive lines. The first two would be manned by militia and the third by Continental Army regulars.

On 15 March, the British launched their attack. The first American line fired and fled, the second line held longer, and Cornwallis launched an unsuccessful attack on the third line. They reformed and attacked the left flank of the line but were overwhelmed by Lee’s cavalry. In retaliation, Cornwallis ordered his artillery to fire grapeshot into the fighting, hitting both British and American troops. Greene retreated since his left was collapsing but the British had sustained substantially greater losses.

After the Battle of Guilford Court House, Cornwallis headed south to Wilmington, North Carolina. Greene gave chase but chose not to attack since much of his militia had returned home. In late April, much to Greene’s surprise, Cornwallis turned and moved north.

Rather than follow with his main force Greene detached Lafayette to harass Cornwallis while he moved south to challenge British Lieutenant Colonel Francis Rawdon for control of South Carolina and Georgia. On 20 April he began a siege of Camden, South Carolina and established a camp on Hobkirk’s Hill. Rawdon managed to launch a surprise attack on Greene’s position on 25 April. Despite being surprised, Greene quickly recovered and was nearly victorious, when his left collapsed, and his cavalry failed to arrive. To avoid a total defeat, he retreated ending the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill. Both sides suffered a similar number of casualties.

On !0 May, Rawdon retreated to Charleston, South Carolina conceding control of much of the interior of the state. There was no longer a major British maneuver unit in the interior and Greene wanted Augusta, Georgia taken to eliminate a threat. He dispatched Henry Lee to Augusta where a strong militia force commanded by Colonel Elijah Clarke was already battling for the city. Their combined force launched a major attack on Augusta on 21 May. After a hard fight they captured Augusta on 5 June.

The Americans then captured a series of British forts, further expanding their control. They besieged the last fort at Ninety-Six, South Carolina and attacked the fort on 18 June. The attack was unsuccessful, but the British soon abandoned the fort. By the end of June 1781, the British controlled only a thin strip of coastal land from Charleston to Savannah.

After resting through much of July and August and receiving reinforcements, Greene’s Army resumed offensive operations against the British who were under the command of Colonel Alexander Stewart. The Americans engaged the British in South Carolina at Eutaw Springs on the Santee River on 8 September. Both sides entered the battle with about 2,000 men.

The Americans approached in the early morning, forcing the British soldiers to abandon their uneaten breakfasts to fight. British Major John Majoribanks secured his unit in a stone house, impervious to Lieutenant Colonel William Washington’s cavalry attacks. When the hungry Americans captured the British camp and began to devour the abandoned breakfasts, Majoribanks surprised them. A four-hour inconclusive bloodbath in the burning sun ended with both sides withdrawing from the field.

More than 500 Americans were killed or wounded in the Battle of Eutaw Springs. The British lost 700 killed, wounded, or missing, the most lost by any army in a single battle during the entire Revolutionary War. Because of his high number of casualties, Stewart withdrew to Charleston to regroup.

The Battle of Eutaw Springs was one of the hardest fought and bloodiest battles of the Revolution and proved to be the last major engagement of the war in the Carolinas. The Americans had won virtually complete control of the southern department.

Congress issued Greene a gold medal and passed a resolution congratulating him for his victory at Eutaw Springs.

Meanwhile Lafayette with his army of about 4,000 had been shadowing Cornwallis’ army as he moved north through Virginia. Lafayette had just been a pest to Cornwallis, but he was always looking for a chance to catch Cornwallis with his guard down. In July 1781 he thought he had his chance.

Cornwallis’ army of nearly 7,000 was near Jamestown Island preparing to cross the James River. Lafayette planned to wait until Cornwallis had half his force on the north bank, and then launch an attack on those on the south bank.

Cornwallis was a very experienced and skillful military leader and prepared a trap to deal with this annoying force of Americans. He made Lafayette believe his army was split to lure him into attacking the entire British force. Lafayette fell for the ruse and the Battle of Green Spring began.

Lafayette advanced in column formation with General “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvania and Virginia troops of about 900 in the van. They engaged British pickets on the road to Jamestown and pursued them towards the James River. They made it to the Harris farm at about 5:00 in the afternoon. They were far in the advance of the rest of the American column when the British launched a withering counterattack.

At this point, rather than fall back, General Wayne, in a very unconventional and bold decision ordered his outnumbered force to fix bayonets and advance on the British line which momentarily stunned the British.

For the next few minutes, the British line and the American line stood about 50 yards apart and fired volley after volley of musket fire into each other. To have stood and fought in an open field at that range would have been a terrifying ordeal, but they stood and fought. One contemporary later called it “Madness!”

After a few minutes of this close fighting, the American troops were forced to fall back quickly. The impromptu advance Wayne had ordered, succeeded in stalling the British advance and allowed American reinforcements to cover his retreat. Lafayette fell back that night. Cornwallis chose not to give chase and crossed the James River. The British had suffered about 75 killed and wounded and the American army suffered about 150 killed and wounded.

The Battle of Green Spring was fierce and bloody and was technically a British victory. However, once again the young American army had gone toe-to-toe and proved it was on par with British regulars.

Cornwallis moved to the tidewater town of Yorktown, Virginia in August. He immediately began fortifying the town and the adjacent promontory of Gloucester Point across the York River. He was to establish a deep-water port and receive supplies and replacements from the British fleet. The British believed their navy would dominate the Cheasepeake Bay and that Cornwallis could maintain seaborne lines of communication with the large British army of General Henry Clinton in New York City.

General Washington ordered Lafayette to hold Cornwallis in Yorktown. Concurrently, Washington’s 2,500 troops in New York were joined by a French army of 4,000 commanded by Count de Rochambeau. Washington and Rochambeau made plans to attack Cornwallis with the assistance of a large French fleet under the command of the Count de Grasse. On 21 August they crossed the Hudson River and marched south. Covering 200 miles in 15 days, the allied force reached the head of Chesapeake Bay in early September.

A British fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves failed to break French naval superiority at the Battle of Virginia Capes on 5 September, denying Cornwallis his expected reinforcements. Beginning 14 September, de Grasse transported Washington and Rochambeau’s men down the Chesapeake Bay to Virginia, where they joined Lafayette and completed the encirclement of Yorktown on 28 September. De Grasse landed another 3,000 French troops carried by his fleet. During the first two weeks of October, the 14,000 Franco-American troops gradually tightened the siege. They defeated the fortified British positions with the aid of cannon fire from de Grasse’s warships.

.

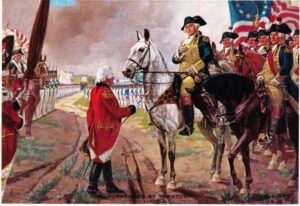

Artist Rendering of British Surrender at Yorktown, VA

On 19 October 1781, General Cornwallis surrendered 7,087 officers and men, 900 seamen, 144 cannon, 15 galleys, a frigate, and 30 transport ships. Pleading illness, he did not attend the surrender ceremony. His second-in-command, General Charles O’Hara, carried Cornwallis’ sword to the American and French commanders. Washington had his second-in-command, Major General Benjamin Lincoln, accept Cornwallis’ sword.

As the British and Hessian troops marched out to surrender their arms and battle flags, the British bands played the song “The World Turned Upside Down.”

A British fleet carrying 7,000 men set out from New York on 24 October to rescue Cornwallis. After entering the bay, Admiral Graves was informed of the surrender and withdrew rather than engaging the superior French Fleet.

Although the war persisted for a while on the high seas and in other theaters, the victory at Yorktown effectively ended fighting in the American colonies. Peace negotiations began in 1782, and on 3 September 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed, formally recognizing the United States as a free and independent nation after eight years of war.

After the surrender, the British evacuated Savannah, Georgia on 11 July 1782 and Charleston, South Carolina on 14 September 1782. The last British troops left New York City on 25 November 1783 ending seven years of British occupation. American troops led by General George Washington and New York Governor George Clinton made a triumphant return to New York City.

General Greene finished the war putting down the remaining loyalist militias and struggling to feed and clothe his army. Congress officially declared the end of the war in April 1783. Greene resigned his commission in late 1783. He initially returned to Newport, Rhode Island, but like many patriots, he faced a mountain of debt. He had paid for much of the supplies for his army and now the creditors wanted their money. Congress, the creditors, and Greene were involved in several plans to pay, but most did not act in good faith. Greene was being hounded so he chose to return to the south where he was loved.

The credit machinations continued until final settlement in 1854. Greene’s estate received only a small sum.

The governments of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia had all voted Greene liberal grants of land and money, including an estate called Boone’s Barony in Bamberg County, South Carolina and Mulberry Grove Plantation near Savannah, Georgia.

Greene made his home at Mulberry Grove Plantation. He purchased slaves to work the plantation, and he settled into his new life. In 1784 he refused appointment to a commission that was to negotiate treaties with Indian tribes, but he did attend the first meeting of the Society of the Cincinnati.

On 12 June 1786, Greene became ill and died on 19 June at the age of 43. He was interred at the Graham Vault in Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah alongside British Lieutenant Colonel John Maitland who had fought against Greene during the war.

Greene’s wife Catherine died in 1814. She had often visited Nathaneal no matter where he was located, including the terrible winter at Valley Forge. She gained the admiration and friendship of the other Continental officers including Washington.

Through the efforts of Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati President Asa Bird Gardiner, Greene’s body was reinterred at a fitting monument in Johnson Square in Savannah on 14 November 1902. His son, George was buried with his father.

General Washington had designated Greene to be his replacement in case he was killed or captured. Cornwallis wrote that Greene was “as dangerous as Washington.” He was able to merge disparate ineffective units into a cohesive fighting force and was a master at integrating the use of guerilla forces.

There are many memorials to Greene throughout the United States. His statue, along with the statue of Roger Williams, represents Rhode Island in the US Capitol. Another statue is nearby in Stanton Park. His statues are found in many other locations. Fourteen counties are named after him as well as a river and many schools. Several US naval vessels have been named after him. The Greene 1774 Homestead in Coventry, Rhode Island is preserved and open to the public.

Nathanael Greene was a great patriot who loved his country and freedom and was willing to fight for them. He is a giant of American history.