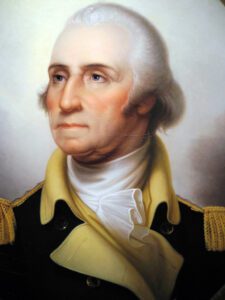

George Clymer was orphaned at an early age but became a successful merchant and politician. He served in both the first and second Continental Congresses and was one of the earliest and most passionate advocates for a complete break from Britain. He was one of only six men who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. He was a dedicated supporter of General George Washington and a trusted official during the Washington presidency. Clymer remained active in politics until his death.

George Clymer was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 16 March 1739, the son of Christopher and Deborah Fitzwater Clymer. Both the Clymer and Fitzwater families were early and successful settlers of Pennsylvania.

George was the only one of three children to survive infancy and he was orphaned at the age of one or seven years old depending on the early records sourced. Christopher Clymer had died in 1734 but his considerable inheritance had dwindled considerably so he had left only a few personal items to George. George’s mother, Deborah, died before George was one year old (or seven).

No matter the exact year, George Clymer was orphaned at an early age and was taken in by his mother’s sister, Hannah, and her husband William Coleman. The Coleman’s were childless. William was a successful and wealthy businessman who was active in local politics. The Coleman mansion was known as Woodford, which still stands and is the best example of colonial architecture in the Fairmont Park section of Philadelphia.

Coleman had helped finance his friend Ben Franklin’s independent printing business. He also worked with Franklin to establish the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society and the College and Academy of Philadelphia (future University of Pennsylvania). He and Franklin worked to arm the city and build fortifications to protect the city from French and Spanish raiders. The pacifist Quaker community officially ostracized Coleman for these militant actions.

The Colemans never officially adopted George, but he was apparently treated as a son and was raised in the comfort of Woodford. He did not attend school but was an avid reader.

Clymer learned character, resolve and business acumen from William Coleman. He began working in Coleman’s business by the time he was 14 years old and was eventually made a partner.

On 22 March 1765 Clymer married Elizabeth Meredith, the daughter of Reese Meredith. Reese was a Philadelphia merchant who was second in wealth only to Robert Morris. George and Elizabeth had eight children with five surviving childhood. George had admitted to previously fathering an illegitimate child in a letter to the Reverend Richard Peters, Rector of Christ Church. Nothing about the mother nor child is ever mentioned, and no more is known.

William Coleman died in 1769 and left the bulk of his estate, including the business, to Clymer. Soon afterward, George merged this business with the Meredith (Reese and son Samuel) business. The merger resulted in a very profitable trading firm.

Years earlier Reese Meredith had struck up a conversation with a young Virginia planter who was sitting alone in a public house and invited him to stay at his house. From then on, when George Washington visited Philadelphia, he stayed with the Merediths.

George Clymer’s family connections put him in the upper strata of power in Philadelphia. His brother-in-law Samuel married Margaret Cadwalader, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Sister-in-law Ann married Henry Hill, the wealthiest wine merchant in Philadelphia. George Washington was one of Hill’s major clients.

The successful Clymer-Meredith merger allowed George to enter Philadelphia politics in 1769. He served on the Common Council, as Justice of the Peace, and associate justice of the City Court. Concurrently, he was becoming more militant in his opposition to Britain’s increasing control over trade. He joined the Proprietary Party, which advocated active resistance to the Crown. In 1765, he and 400 Philadelphia merchants signed a non-importation agreement in response to the Stamp Act and he helped organize a boycott of the Townsend Act duties. George also authored (under alias) many articles and pamphlets blasting British policy.

Clymer’s outspoken militancy on liberty and independence did not sit well with most influential Philadelphians. Most were Quaker and most were pacifists. They opposed any actions that could lead to war. Despite Quaker calls for caution and reconciliation, Clymer had many allies. His brother-in-law Samuel was disowned by the Quakers for his militancy and Samuel’s wife’s brothers were ardent patriots. When war began John Cadwalader organized the famed 3rd Battalion of City Troops who were known as the “Silk Stocking” Troop. Cadwalader served with Washington at Brandywine and Princeton. Wine merchant Henry Hill publicly expressed revolutionary ideas. Independence was slowly becoming mainstream.

In 1773 Clymer went to Boston for medical treatment. While there he met the leading New England revolutionaries, including John and Sam Adams, and John Hancock. In his letters, Clymer expressed admiration for the radicals and disdain for the Philadelphia and New York merchants who he saw as self-serving.

The Tea Act of 1773 was a rallying point for resistance nationally. The Boston radicals communicated with leading Whig radicals in Philadelphia. Clymer and Thomas Mifflin established a committee of correspondence to coordinate information and resistance. News of the 16 December 1773 Boston Tea Party quickly reached Philadelphia, and ten days later a British ship reached Philadelphia. Clymer convinced the captain to return to England without attempting to unload his cargo of tea.

The British retaliated to patriot resistance in 1774 by closing Boston Harbor, passing the Coercive Acts (known as Intolerable Acts to colonials), and by military occupation of Boston. These acts by the British Parliament crossed a line that was inescapably leading to armed revolution.

Paul Revere arrived in Philadelphia in May with the Boston Circular Letter that listed the British actions and called for the colonies to meet to discuss reaction to the British. In Philadelphia, moderates and even the Whig party advocated caution and negotiation. Clymer was incensed by this display of timidity. He returned to Boston to find the British to be an alien occupying force, but which was no longer in control.

In Philadelphia Clymer’s views were rejected and moderates were chosen to represent Pennsylvania in the First Continental Congress. However, radical views were winning out in congress and a boycott of trade with Britain was passed. George Clymer was elected to the Philadelphia committee to enforce the boycott. He played a prominent role in open acts of opposition to the Crown.

Open warfare began on 19 April 1775 when British and American forces clashed in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Militia forces were being organized in the colonies and on 19 June 1775 George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. George Clymer joined the Committee of Safety, organized by Ben Franklin and Robert Morris, to arm and fortify Pennsylvania. George was also devoted to efforts to mobilize and supply the Continental Army.

The Pennsylvania delegation to Congress voted for independence by a slim majority on 2 July 1776 after being released from instructions to vote against it. A new Pennsylvania delegation of radicals, including Clymer, was elected and signed the Declaration of Independence on 20 July.

Clymer spent much of the summer of 1776 working on a new state constitution, although it turned out to be a huge disappointment. He and 22 others out of the 96-man state convention, refused to sign the completed document.

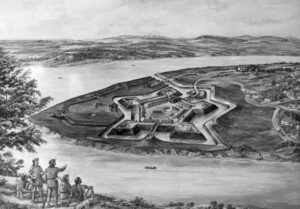

When Clymer returned to Congress in the fall of 1776, his first assignment was to inspect the defenses and conditions at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga. His report was instrumental in focusing Congress’ attention on procurement and supply and on the plight of wounded and sick Continental soldiers

Upon his return Clymer discovered he had been elected to the new Provincial Assembly and Council as a leading anti-constitutionalist. Reform efforts failed and he resigned his seat when the state government was organized under the Articles of Confederation in 1778.

In December 1776, the British army had advanced toward Philadelphia, so Congress moved to Baltimore, Maryland. Clymer, Robert Morris, George Walton, and a Georgia delegate remained in Philadelphia to continue the work of keeping General Washington’s army supplied. They opened an office in Philadelphia until Congress returned in February 1777.

Clymer had moved his family to a farm near Chester, Pennsylvania, 25 miles south of Philadelphia, so they would be close. He often rode horseback late in the day to spend the night with them, returning at dawn the next day.

The British did occupy Philadelphia in September 1777, and Congress re-located to York, Pennsylvania. The Clymer family also moved to York.

In December 1777, Clymer volunteered to investigate the deteriorating situation on the western frontier and reports of treason at Fort Pitt (now Pittsburg, Pennsylvania). Also, the Delaware and Shawnee Indian tribes were threatening to switch their allegiance to the British. He was at Fort Pitt for four months, two with a Virginia delegate.

Clymer was not impressed with the quality of the frontiersmen. He believed they were dishonest, corrupt, and self-serving. He doubted they could hold the frontier. Clymer did, however, manage to repair relations with the Indians.

When Clymer returned, provincial politics prevented his re-election to congress and for the next two years he devoted his time to his commercial interests. At the time, his affairs were mainly concerned with large tracts of land in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and the New York frontier that he had inherited. George’s wealth was increasing substantially.

The British withdrew from Philadelphia in the summer of 1778, so Clymer and his family returned despite out-of-control inflation. By the spring of 1780, the revolution was seriously in danger. Paper money was worthless, the military procurement system was completely broken, the states refused to supply any funds, and the army was rapidly running out of supplies. Even the stocks of flour were almost exhausted, and General Washington doubted the army could last until the harvest.

Under the leadership of Clymer, Philadelphia merchants banded together to charter a private bank, the Pennsylvania Bank. They raised funds to purchase supplies for the Army until Congress could get around to paying for them. George was a co-director of the bank, and it grew into a huge corporation. They had representatives scouring the countryside in search of supplies. They delivered thousands of barrels of flour and corn, casks of rum, and hundreds of tents to the needy army.

The merchants won the undying gratitude of General Washington. The Commissary General of the army wrote that they had saved the army from dissolution. Unfortunately, there were accusations of corruption despite the bank having been chartered as a non-profit. Clymer pointed out that no investor made a profit and that many had lost money.

Because of the success of the Pennsylvania Bank, Clymer was again appointed to Congress in 1781. The country was still having serious financial problems and he was appointed to the finance committee which was chaired by Robert Morris. They were tasked with establishing a national bank and Clymer traveled to the southern states to solicit subscriptions but was unsuccessful.

George Clymer left congress in late 1782 and moved his family to a home near Princton, New Jersey where he retired. Retirement ended in 1784 when he moved back to Philadelphia to serve in the Pennsylvania legislature. Clymer became more convinced that for the country to survive, a strong federal union had to be formed with the authority to tax and control commerce.

Independence initially was accompanied by economic problems and unrest. Most of the great powers and many Americans were expecting the nation to fail. During the winter of 1786-87, inflation was rampant and paper money was worthless. Riots erupted in Vermont and New Hampshire, and Captain Daniel Shays launched a rebellion of angry farmers in western Massachusetts. American leaders called for a national convention to re-write the Articles of Confederation. This convention began on 14 May 1787 and reached a quorum on 25 May.

Clymer was elected a delegate to the convention which became known as the Constitutional Convention. He actively campaigned for a strong centralized national government. The debate was lively, contentious, and often bitter, but in September a draft was adopted, signed, and submitted to the states for ratification. George Clymer signed the Constitution and then was a leader in the Pennsylvania ratification convention. The Constitution of the United States was ratified by the states in July 1788. George Washington was elected president and John Adams vice president on 6 April 1789. The Bill of Rights was added on 1 March 1792.

Clymer was elected to the first United States Congress which convened on 4 March 1789. He proved to be a staunch Federalist and supporter of President Washington. He worked to strengthen government finances by import duties and excise taxes.

In 1791, Congress levied a tax on every barrel of whiskey distilled in the United States to help pay off the national debt. After serving one term in Congress, Clymer was appointed to the position of Supervisor of Revenue for Pennsylvania, and it was his disagreeable and often dangerous task to collect the new taxes.

Every year the farmers in Western Pennsylvania converted any excess grain yields to whiskey which provided them with much-needed cash. They defied the Federal tax in what became known as the “Whiskey Rebellion”. Many of the farmers were veterans of the Revolutionary War and believed that defying the tax was standing up for the principles of the Revolution.

The Whiskey Rebellion was put down in 1794 by 1,500 militia, including George’s son Meredith. This force was led by President Washington and the rebellion ended without an armed clash. All the farmers that were arrested were later acquitted or pardoned.

The outcome of the Whiskey Rebellion firmly established the right of Congress to levy taxes.

Meredith Clymer was killed at Fort Pitt in 1794 and George resigned his position, which he then found distasteful. He returned to private life, but not for long.

In 1796 President Washington again called on Clymer appointing him one of three commissioners to negotiate a new treaty with the Creek and Seminole Indians in Georgia. Clymer sided with the Creeks against what he believed were illegal attempts to annex their tribal lands. The treaty that was negotiated helped turn the southern tribes away from dependence on the Spanish to an alliance with the Americans.

After the treaty negotiations, Clymer once again returned to private life, but remained very active. In 1803 he became president of the new Philadelphia Bank and in 1805 helped found the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, also becoming president of that organization. He served in both positions until his death. He helped organize the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, and he was already a trustee for the College and Academy of Philadelphia (now University of Pennsylvania). At his death, Clymer had served in that trustee position for 22 years.

After a brief illness, George Clymer died on 23 January 1813 at Summerseat, an estate a few miles outside Philadelphia at Morrisville. He had purchased and moved to Summerseat in 1806. He was buried in the Friends Meeting House Cemetery at Trenton, New Jersey.

After the death of George, Elizabeth and her son Henry and his family moved to Northumberland County, PA. She died there in 1815. Her grave location is not known.

Attack Transport USS George Clymer (APA-27) honors George Clymer, a town in Indiana County, Pennsylvania and a town in New York are named after him as is a school in Philadelphia. A Clymer marker is in the Memorial to the Signers of the Declaration in Savannah, Georgia and in the national Memorial to the Signers in Washington, DC.

The Signer, sculpted by Evangelos Frudakis in 1980, was dedicated in Signers Park on the former site of the Gilbert Stuart House in 1982 during Philadelphia’s Tercentenary. Inspired by George Clymer, “commemorates the spirit and deeds of all who devoted their lives to the cause of American Freedom.” The Signer is looking heavenward, holding a founding document within his grasp. The bronze statue, standing 9-1/2 feet high on a 6-foot granite base, was a gift of the Independence Hall Association.