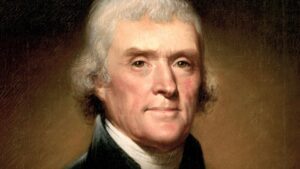

I admire Thomas Jefferson so much that I named my only son after him. Jefferson was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, and the nation’s first secretary of state, second vice president, and third president. His phrase in the Declaration, “all men are created equal” was the most radical and revolutionary ever expressed. His words have come ringing through the years and are still used as a rallying cry for people all over the world who seek freedom. Next to George Washington, he is probably the most admired man in American history.

President John F. Kennedy honored Jefferson at a 1962 dinner honoring 49 Nobel Prize winners by stating: “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” This was quite a tribute to Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson was born on 13 April 1743 on his father’s 5,000-acre plantation, Shadwell. Shadwell is located at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains along the Rivanna River in the Piedmont region of central Virginia. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a successful planter and surveyor. His mother was Jane Randolph a member of one of the most distinguished families in Virginia. The Jefferson’s had two sons (Jefferson was the eldest) and six daughters.

When Thomas was three years old the family temporarily relocated to Tuckahoe Plantation located in the Richmond area. The move was necessitated by the death of William Randolph III whose wife had preceded him in death the year before. Randolph’s will had a provision asking that Peter Jefferson come to Tuckahoe to care for his three orphaned children. Peter packed up his entire family and moved to Tuckahoe.

The Jefferson and Randolph children lived together at Tuckahoe for six years when Thomas began his formal education. He boarded with a local schoolmaster to learn Latin and Greek. In 1760 he enrolled in the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. There he studied under William Small who brought the latest Enlightenment thinking from Scotland and he dined frequently with Governor Francis Fauquier and other high-ranking Virginia officials.

Young Thomas was a very dedicated student. He studied science, mathematics, rhetoric, philosophy, and literature. He spent 15 hours a day studying, three hours practicing the violin, and six hours eating and sleeping.

William and Mary educated the sons of the most wealthy and influential Virginia families. Thomas Jefferson became acquainted with many others that would become involved in future revolutionary politics and military. Away from college, he became acquainted with a young man whose pen would also become famous by becoming the voice of revolution—Thomas Paine.

In 1762 Jefferson began legal studies under George Wythe who also taught John Marshall and Henry Clay. When he was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1767, Jefferson was probably the nation’s best-read lawyer. His practice involved representing mainly small-scale western county planters in land disputes. He gained a reputation as a formidable attorney but came across as an indifferent speaker and somewhat shy.

Thomas Jefferson’s father had died in 1757. As eldest son, he officially inherited Shadwell in 1764 at 21 years old; however, he had to lease the property from his mother until she died in 1776 because she had a “life estate” for the property. He operated Shadwell mainly as a tobacco plantation.

Jefferson was a meticulous manager and record keeper and was actively involved in the slave trade to keep his slave population young and productive. The records also indicated that he could be a hard taskmaster, and his punishment could be severe.

About 200 slaves were needed to operate Shadwell and over Jefferson’s lifetime he owned around 600 slaves. He defended the institution of slavery most of his life, and he believed blacks were inferior to whites. His opinions were not unusual during his time. Most people in the south and many in the north agreed with Jefferson.

Interestingly, in 1781 Jefferson authored “Notes on the State of Virginia,” which included a discussion of slavery. He described the terrible effects of slavery on both blacks and whites and asserted that it violated the principles of the Revolution. He also stated his belief in the inferiority of blacks. His stated views on slavery seemed to place him in the forefront of the anti-slavery movement, but his actions did not back up his words in “Notes.”

From his childhood, Jefferson had dreamed of living on a mountain and in 1768, he made the decision to build his home on an 867-foot-high mountain on Shadwell Plantation. He eventually named his new home Monticello (Little Mountain in Italian). Also in 1768, he was a successful candidate for the Virginia House of Burgesses.

In 1770, fire destroyed the manor house at Shadwell. Thomas’ books and papers were lost in the fire. After the fire, Thomas moved to Monticello, which consisted of one small brick structure. (Now called the South Pavilion.) As construction continued over the years under Jefferson’s close supervision, he referred to Monticello as “my essay in Architecture.” He designed the complete structure. Throughout his career Jefferson would pursue politics with periods of seclusion at his beloved Monticello.

Jefferson entered politics just as serious opposition to the taxation policies of the British Parliament was beginning. This provided him and many other colonial politicians with the vehicle which they would ride to fame and a new nation.

Thomas Jefferson was freckled with reddish blond hair, hazel eyes, and a reddish complexion. He was tall for his day (about six feet two inches), awkward and gangly, shy, and was no public speaker. His writing was eloquent and powerful, but he rarely spoke in debates in the Burgesses or later in the Continental Congress. Jefferson’s compositions spoke for him.

In 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wales Skelton, an attractive and delicate young widow whose dowry more than doubled his holdings in land and slaves. The couple moved into the partially completed Monticello. The marriage produced six children but only two daughters survived to adulthood.

In 1774, Jefferson wrote “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” which was published without his permission. This essay stated that the colonies’ ties to Britain were a “voluntary loyalty” to the crown and made Jefferson known beyond Virginia as an early advocate of independence.

Jefferson’s new reputation resulted in the Virginia legislature appointing him a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. He rode into Philadelphia—and into American history—on 20 June 1775 in an ornate carriage drawn by four horses and accompanied by three slaves, and with a firm belief in the American cause.

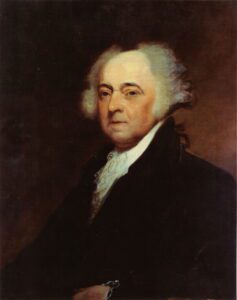

Jefferson’s shyness and poor oratory prevented him from taking an active part in the congressional debates. John Adams remembered that he was silent even in committee meetings but always strongly supported independence. His main job was to draft congressional resolutions so on 11 June 1776 he was appointed to a five-man committee to draft a document to cite the reasons behind Richard Henry Lee’s resolution to break from Great Britain.

The committee was composed of two New England men, John Adams of Massachusetts, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut; two men from the Middle Colonies, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, and Robert R. Livingston of New York; and one southerner, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

The draft was prepared in a few days with Jefferson being the main author of this document that would change the world. Jefferson later claimed he was not striving for “originality of principle or sentiment” but was seeking to provide “an expression of the American mind,” which meant putting into words ideas already accepted by most Americans. This describes the longest section of the Declaration, which cites the grievances against George III. It does not, however, describe the 55 words that are the bedrock of our Republic and probably the most momentous in human history:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Much to his chagrin, Congress debated and edited more than 20 percent of Jefferson’s document, but they made no changes to the above section. His contemporaries regarded the final Declaration as a collective effort of the congress, and Jefferson was not recognized as the principal author until the 1790s.

Jefferson returned to Virginia in October 1776 and began an extensive reform of the state’s legal code to bring it in line with the principles of the Revolution.

His three areas of reform suggest his own political vision. First, he proposed and secured changes that eliminated primogeniture (primarily inheritance by eldest male) entail (restriction of sale of estates to protect family and class possession) and all other remnants of feudalism that discouraged broad distribution of property. Second, he proposed education reform to guarantee access to lower levels of schooling to all citizens and state support for the most talented students to attend higher levels of education. Third, he advocated a law prohibiting establishment of a state religion and he proposed separation of church and state.

The last two proposals were bitterly contested, particularly those on religious freedom, which were not enacted until 1786.

These reforms demonstrate Jefferson’s vision of the role of government. He believed that the privileges and impediments of the past had to be left behind to allow the natural energies of individuals to flow freely. He saw the American Revolution as the first shot in what would become a global battle for liberation from despotic and coercive governments. History shows he was right.

Jefferson was elected governor of Virginia in 1779 and was riding a wave of political success when disaster struck on two fronts. He was caught off-guard by a surprise British invasion of Virginia in 1780. The state was not prepared and was defenseless. His flight from the approaching British was somewhat unfairly described in the local press as a “cowardly act of abdication.” This would be recalled by his political enemies throughout his career. The second disaster was in September 1782 when his beloved wife died following the difficult birth of their third daughter in May.

The two disasters caused him to vow to never again desert his family for the country, but this sincere vow was short-lived. He reluctantly agreed to again serve as a delegate to the Continental Congress in December 1782. His major, and especially important, contribution to this congressional session concerned the admittance of new states. Jefferson proposed and congress established that territories in the west had status equal to the original states once certain conditions were met (such as adequate population, and a functioning territorial government).

Jefferson needed to escape things that reminded him of his beloved Martha, so in 1784 he agreed to replace Benjamin Franklin as American minister to France. Legend has it that he agreed to “succeed” Franklin noting that no one could replace him.

During his five years in France, Jefferson accomplished little diplomatically mainly because no European power wanted to have treaty relations or trade with a nation they believed would fail. The American government was obviously weak and Great Britain controlled over 80 percent of America’s trade. Efforts by Jefferson to reopen French markets failed since France was already moving towards a political crisis and a brutal revolution.

Jefferson did help negotiate a $400,000 loan from Dutch bankers, but John Adams who was minister to the Court of St. James (Britain) was the main negotiator. This loan allowed America to consolidate its European debts.

During his Paris years Jefferson enjoyed the local arts, wine, and food, but warned American tourists to avoid the sins of European society. He brought his two daughters to Paris because of his love for them, but he placed them in a convent. He then wrote them stern lectures about proper behavior. Jefferson, however, had a steamy and very public affair with Maria Cosway, a married woman.

Jefferson also had a long sexual relationship with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. She had accompanied him to Paris. Some believe this relationship began in France when his affair with Cosway ended, but I doubt this. I believe the Sally Hemings relationship began before his appointment to France. I don’t think he would have brought her to France if she was not already a sexual partner. Jefferson fathered several children with Hemings, and their descendants are now recognized as part of the Jefferson family.

As Louis XVI tried to address France’s financial crises, Jefferson believed the French Revolution would be bloodless and result in a constitutional monarchy. Influenced by moderates like the Marquis de Lafayette, he was oblivious to the fact that the French were about to explode into the bloody Reign of Terror. Jefferson believed the French Revolution would follow the American model. He was lucky to depart France in late 1789 just at the onset of mob violence.

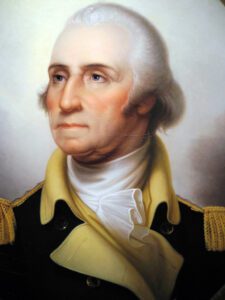

When Jefferson returned to the new United States, he was tapped by President George Washington to serve as the first secretary of state. This was a tall order because there had never been a lasting republican nation the size of the United States and no one was sure of how it would turn out.

Jefferson had been in France during the 1787-1788 constitutional debates and the state ratifying conventions, so he entered the bitter debates of the 1790’s without a history of constitutional convictions. Unlike his close friend James Madison, his major concern was that the Constitution did not include a Bill of Rights.

During his 1790-1793 service as secretary of state, Jefferson was responsible for foreign policy, but the cabinet was divided into three factions. All embraced the neutrality doctrine but differed on what neutrality looked like. Washington and Vice President John Adams favored absolute neutrality, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton pushed for a pro-English neutrality, and Jefferson favored a pro-French neutrality. Jefferson believed the Franco-American treaty of 1778 obliged the US to this policy to honor the French support during the American Revolution.

Jefferson also insisted that the French Revolution embodied the “spirit of 76” and even when it turned into a blood bath of executions and mayhem, he insisted they were temporary excesses. He further believed the excesses were justified by larger and more important issues. He never repudiated this view.

When Jefferson was informed of Shay’s Rebellion in 1786, he stated: “I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.” This attitude dovetails with his view of the French Revolution.

The Jefferson view of foreign policy never wavered from his admiration of the French. Even after his retirement from office in 1793, he actively opposed the Neutrality Act of 1793 and the Jay Treaty in 1795. He saw these as betrayal of the French and as pacts with the British “harlot.”

John Adams was president 1797-1801 and since Jefferson received the second most votes, he was elected vice president. Jefferson worked behind the scenes to undermine Adams’ efforts to maintain absolute neutrality. Jefferson blamed the “Quasi-War” with France on “our American Anglophiles” rather than the French. His view was that England was corrupt and despotic and France was enlightened and the wave of the future.

On the domestic scene, Jefferson saw the efforts to develop a strong central government as a plot to subvert the true meaning of the American Revolution. Alexander Hamilton was working to establish a federal financial system and Jefferson was bitterly opposed to Hamilton. Jefferson believed the Federalists were trying to install monarchy and an American aristocracy to rule the country.

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists formed political parties because of their bitterly different visions on the role of government. George Washington and some others believed the formation of political parties was divisive, but it was a natural progression of organization. The parties called themselves Federalists and Republicans (later Democratic-Republicans).

Early American politics were very turbulent, personal, and nasty. Today’s politics are much the same, but Jefferson and his contemporaries had just won a brutal revolution against one of the strongest military powers in the world at that time. They had laid out the principles and purposes of a completely new type of government in the Constitution, but now they had to make it work. This was not an easy task and most of the world believed they would fail. I believe they very may well have failed if not for George Washington who was a strong, stabilizing, and calming influence who brought real class to the American image.

The founders were spiritual, intelligent, tough, opinionated, and ambitious. Each one saw the role of government differently. All of them were willing to fight for their vision of government and some were willing to destroy their opponents any way they could. In the end, they did great, and the government of “we the people” emerged.

The partnership of Jefferson and James Madison was especially powerful. John Quincey Adams described the partnership as follows; “the mutual influence of these two mighty minds on each other is a phenomenon like the invisible and mysterious movements of the magnet in the physical world.” Their opposition to a strong central government gained them the label of “traitors” by the Federalist press.

Jefferson was duplicitous and hypocritical in his dealings and some historians are negative about his moral and public character. He was leading a political party while insisting that parties were “evil agents.” In 1796 he unsuccessfully ran for president against John Adams while claiming he did not know he was a candidate.

The 1800 election was one of the most fiercely contested and nastiest campaigns in American history. The Federalist press described Jefferson as a pagan and atheist, conspirator against the Washington-Adams administrations, a utopian dreamer, an anarchist, and a cunning behind-the-scenes manipulator of Republican propaganda. He was guilty of the last accusation.

Always acting through intermediaries, Jefferson paid journalists to libel his old friend John Adams and he offered the vice presidency to Aaron Burr for delivering New York’s electoral votes. When Burr and Jefferson tied for the top job, the House, after a lot of backroom wheeling and dealing, elected Jefferson on the 36th ballot. Burr was elected vice president.

Many wondered if the new nation could survive a Jefferson presidency since he was so defiantly against a strong central government. It was believed by some that he would completely dismantle the government that he had helped found. Despite the worries this was the first peaceful transfer of power from one party to another in the nation’s history.

Jefferson gave his inaugural address on 4 March 1801 and his tone was conciliatory stating that “We are all republicans—we are all federalists.” He described his election as a return to the original intentions of the Revolution after those who had erroneously believed in a powerful central government. The people he said, were now unburdened of government restrictions.

Once he selected a cabinet the real work of governing began. Jefferson had few cabinet meetings because he preferred to conduct business in writing. He did the same with Congress and gave all his presentations in writing. During his two terms as president, Jefferson only delivered two speeches—his inaugural addresses. This was due to his poor oratory skills, and his desire to reduce the visibility of the president.

By far the major achievement of Jefferson’s first term, and of his presidency, was the purchase of Louisiana from France in 1803. Nepoleon needed the cash to finance a new war with England. The cost of fifteen million dollars was a huge sum in 1803 and it substantially increased the national debt; however, in the long run it was a stupendous bargain. Louisiana stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and essentially doubled the size of the United States. It also removed the threat of a major foreign power from America’s borders.

Many historians believe the Louisiana Purchase was the boldest executive action in American history. Jefferson suffered considerable criticism for his action, but he never wavered. He correctly saw it as the future of the country. Even before word of the French approval reached the United States in July 1803, Jefferson dispatched his private secretary, Merriwether Lewis, to lead an exploration of Louisiana and beyond to the Pacific Ocean.

Jefferson easily won reelection in 1804 over Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, and his policies continued to reflect his desire for decentralization. He was dismantling much of the government including the military and federal tax programs. His policies initially enjoyed success because the pause in war between England and France allowed trade with both countries resulting in American prosperity.

The prosperity did not last long because Napoleon’s war against England resumed resulting in naval blockades in the Atlantic and Caribbean that severely curtailed American trade. Jefferson responded with the Embargo Act of 1807. This act made matters worse because American trade with the major powers was too small to influence their actions and only American traders suffered. In addition, enforcement of the act required coercive powers that Jefferson opposed on principle.

Despite significant pressure to take sides in the Napoleonic War, Jefferson attempted to maintain American neutrality. This action only enraged the belligerents.

Jefferson’s second term was marred by some actions that were contrary to his eloquent words. The Federalist Party was dead, but some opposition survived, particularly in New England. Jefferson was outraged by the persistent attacks on his policies and character and instructed the attorneys general in those states to seek indictments against his detractors. This was a clear violation of the First Amendment to the Constitution and of Jefferson’s stated support of a free press and freedom of expression.

Aaron Burr was also a victim of Jefferson’s wrath. Burr had killed popular Alexander Hamilton in a duel, and many wanted him tried for murder. He was later accused of treason because of a mysterious expedition to the American Southwest and Spanish Texas. Burr allegedly planned to detach some territory from the United States and to establish himself as dictator in Texas. Jefferson illegally issued an order to convict Burr without a trial and sent federal agents to pursue him.

The charges of treason against Burr were never proved because of a distinct lack of evidence. Burr turned himself in and was tried twice and was acquitted both times. Jefferson still demanded Burr be convicted and the feds still pursued him. Finally Chief Justice John Marshall served as judge in the final Burr trial. Burr was again acquitted.

Jefferson’s demands for a guilty verdict against Burr and the pursuit by federal authorities was clearly unconstitutional, illegal, and unbecoming of the President of the United States.

By the time he left office in March 1809, Jefferson was a tired and beaten, and I would say bitter man. He was anxious to retire to his beloved Monticello.

Jefferson maintained an active schedule in retirement. His day was organized. He rose at dawn, bathed his feet in cold water, and spent the morning on his correspondence (one year he wrote almost 1,300 letters), and working in his garden. Each afternoon he took a two-hour ride around his grounds. Dinner was usually with his daughter Martha and her 12 children and many guests. Monticello sometimes housed 50 guests. The lack of privacy caused him to build another house on his Bedford estate about 90 miles away for occasional seclusion.

Three architectural projects consumed Jefferson during his life and remain as his physical legacy. Monticello was always a work-in-progress that was never completed. This beautiful neoclassic manor house and grounds attract thousands of visitors every year. The mansion at Bedford (Poplar Forest) is also neoclassic and a perfect octagon. The site of the University of Virginia was selected and surveyed by Jefferson. He chose the Pantheon of Rome as the model for the rotunda, which is flanked by two rows of living quarters for students and faculty.

The university embodies everything Jefferson. He selected the books for the library, defined the curriculum, picked the faculty, and chaired the Board of Visitors. Unlike other colleges and universities of the day, the University of Virginia had no religious affiliation and imposed no religious requirements on students. There was no code of conduct except a self-enforced honor system.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were giants of the American Revolution, but they became political enemies during the tumultuous formation of political parties in the 1790’s. In 1812 Benjamin Rush successfully arranged a reconciliation between the two. He described them as “the North and South poles of the American Revolution.” They had genuine differences in their concept of government, but they respected each other, and they exchanged 158 letters between 1812 and 1826. Most historians believe these letters are the most intellectually impressive correspondence between statesmen in American history.

In late June 1826 Jefferson was invited to attend the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in Washington, D.C. Jefferson could not attend because he was in no physical condition to leave Monticello, so he drafted a statement to be read in his place. These were his final words to the people of the United States:

“May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government.… All eyes are opened or opening to the rights of men. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few, booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others; for ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them.”

As these words were being read in Washington, Jefferson was dying at Monticello. He died about half past noon on 4 July 1826. His last conscious words were the preceding evening when he asked, “Is it the Fourth?” In Quincy, Massachusetts, John Adams was also dying. He died in the afternoon of 4 July 1826, and his last words were: “Thomas Jefferson still lives.” It is amazing but fitting that these two American giants should die on the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson is buried at Monticello. He designed his gravestone and dictated the epitaph which reads:

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

& Father of the University of Virginia

The original monument was erected in 1833 but visitors chipped off fragments for souvenirs. This stone was removed to protect it. Congress funded a new granite stone which was erected in 1883. The family donated the original stone to the University of Missouri in 1885. Missouri was a part of the Louisiana Territory.

Like many of our founders, Jefferson was deeply in debt during his later years. However, Jefferson had been in debt most of his life because of debt inherited from his father-in-law in his wife’s dowry, but mostly because of his lavish lifestyle. By the end of his life, he owed more than $100,000.00 (several million dollars today) and there was no way his heirs could inherit any of his estate. Everything, including Monticello, was auctioned off and Jefferson’s daughter, Martha, was forced to accept charity to sustain her family.

Jefferson has been honored in so many ways that I cannot possibly catalog them. I will only say that his memorial in Washington, D.C. is simple and one of the most beautiful. His commanding statue stands before one of his famous statements etched into the wall:

“I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man”

At the start of this bio I expressed how much I admire Thomas Jefferson. I recognize that he had many serious flaws, however, his flaws make him a normal man. I could never admire a man that seemed perfect because I would know it coudn’t be true.

Ideas and decisions are made and influenced by our personal beliefs and the culture we live in. Society is always evolving, and beliefs change. Even religion evolves over time. My family fought on both sides of the Civil War when thousands of white men died to free black slaves. Jim Crow and segregation were eliminated in my time and today black and brown people enjoy the same rights as whites, which fulfills Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence.

I am proud of all my ancestors and all Americans who have preceded me. They made decisions that were often flawed, but they made decisions and then lived with the results.

The Bible declares: “judge not, lest ye be judged.” Maybe we should all remember that passage and try to live by it.