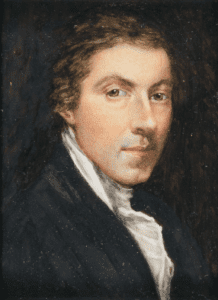

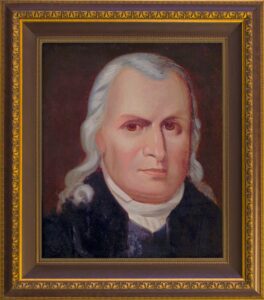

William Paca of Maryland was a wealthy landowner and brilliant lawyer who was an early and passionate advocate of separation from Britain. He was also a supporter of states’ and individual rights. He was a delegate to both the first and second Continental Congresses and was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. After the War for American Independence, he championed veterans’ benefits. Paca was also active in Maryland politics, serving as a judge and the third Governor of the state.

Born on 31 October 1740 north of Baltimore at Chilbury Hall near Abingdon in what is now Harford County, William Paca was the second son of John and Elizabeth Smith Paca. The couple had seven children, two boys and five girls. John was a prominent planter and landowner. Elizabeth was from a wealthy Maryland planter family. William was the fourth generation of Pacas in Maryland.

Each generation had added to the wealth and prestige of the family. William’s great-grandfather, Robert, was brought to the colonies before 1660 by John Hall who owned a plantation in Anne Arundel County. Robert apparently was indentured to Hall as a servant for the cost of his passage. When Hall died, Robert married his widow and instantly acquired a family, position, and much property. Each succeeding generation purchased more land, married well, added to the family wealth, and served in prominent local and colony positions.

Little is known about William Paca’s early years because all his personal papers and diaries were destroyed when his plantation home on Maryland’s Eastern Shore burned in 1879. (The present home was built in 1936 and is privately owned.) However, William probably had the same experiences as the sons of other wealthy planters. He probably received a classical education which would have included Latin, classical literature, and religion.

When he was 12 years old, William and his older brother, Aquila, were sent to the Academy and Charity School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. William graduated from the College of Philadelphia (Now University of Pennsylvania) in 1759 with a BA Degree and in 1762 he received an MA Degree. As important as education, he became acquainted with powerful and well-connected men in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

William moved to Annapolis (Capital of the Province) when he was 19 years old to study law with Stephen Bordley, the preeminent lawyer in the area. He also helped found a debating society, which allowed him to develop speaking skills and further his social and political contacts. It was here that he met Samuel Chase who would also be a signer of the Declaration of Independence. They became life-long friends.

Paca completed his law education at the Middle Temple in London, England, which added to his prestige. He was admitted to the bar in 1761 and entered private law practice in Annapolis in 1763. He had everything needed to launch a successful law career, except for the social status to guarantee success and to allow him to easily enter colonial politics. That problem was solved on 26 May 1763 when he married Ann Mary (Molly) Chew.

Molly was the daughter of Samuel and Henrietta Maria Lloyd Chew. Samuel died when Molly was an infant. She was related to many of the most prominent and wealthy families in the colony. She was the direct descendent of John Chew who arrived at Jamestown, Virginia in 1622. She was raised by her stepfather, Daniel Dulany, one of the richest and most politically influential landowners in Maryland.

William Paca built an elegant Georgian mansion with a two-acre pleasure garden in Annapolis immediately after his marriage to Molly. William and Molly moved into this mansion as soon as it was completed about two years later. When in the country, they resided at Wye Plantation in Queen Annes County, which William had purchased about 1760. They had three children but only one, John Philemon, survived childhood.

Paca and Samuel Chase were both early advocates of independence and they founded the Anne Arundel County Sons of Liberty in 1765. They organized public sentiment in Maryland against the hated British Stamp Act. American resistance led to the act being repealed on 18 March 1766.

Paca’s involvement in the resistance made him popular with the public and he was elected to the Annapolis Common Council in 1766. In 1767, he was elected to be a delegate to the Lower House of the Maryland Colonial General Assembly. His political career was underway, and his popularity and influence increased rapidly. He gained a reputation for hard work behind the scenes. Paca left the limelight to others, such as Samuel Chase.

William Paca spent much of his time writing letters and newspaper articles supporting independence. He also wrote many of Chase’s speeches. Despite working in the background, Paca could take effective lead at times. In 1773 the governor would not rule favorably on a law that Paca and Chase supported, so they staged an interesting protest. They formed a procession leading to gallows where they hanged the law. Then they placed the law in a coffin and buried it while guns were fired from a schooner owned by Paca.

Things were going good for William Paca. He was considered to be one of the finest lawyers in Maryland and his political career was developing. However, on 15 January 1774 Molly died. She was 38 years old and probably died as a result of childbirth. Molly was buried on their Wye Plantation.

Although grief stricken, William had little time for mourning because the situation with Great Britain was eroding every day. The colonists were refusing to knuckle-under to the British and the British continued to turn the screws expecting the Americans to back down.

The British Parliament enacted the Boston Port Act that was to take effect on 1 June 1774. This act was in retaliation for the 1773 Boston Tea Party. It closed the port of Boston and demanded payment for the tea that had been dumped in the harbor. Paca organized Maryland committees to oppose the Port Act, and he was elected to the First Continental Congress, arriving in Philadelphia in September 1774.

In Philadelphia William Paca became friends with John Adams who later described him as a “deliberater” (sic). The first Congress adjourned in October. They had prepared and signed the Continental Association that declared a boycott of British trade.

William was also a delegate to the Second Continental Congress which convened on 10 May 1775. War had already begun at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts in April 1775, but Congress drafted the “Olive Branch Petition” and sent it to the King in an effort to defuse the situation. The King turned it down.

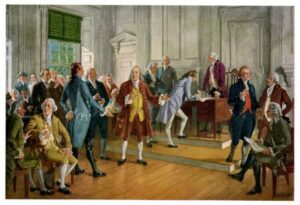

Revolution and independence were in the air, but the Maryland legislature denied their congressional delegates the freedom to vote for independence. Paca and his fellow delegates traveled throughout Maryland to whip up support for independence and the legislature finally released them to vote their conscience.

They voted for the draft Declaration of Independence on 2 July 1776, the final draft on 4 July and signed it on 2 August. Paca was acutely aware that challenging and dangerous times were ahead before independence could become a reality.

Paca served in the Congress for the rest of 1776 and 1777. He was also elected to the Maryland Senate in November 1776, and was appointed judge of the General Court in 1778. He was charged with the job of maintaining stability on the Eastern Shore of Maryland where there were outbreaks of treason and insurrection. He resigned late in the year after accomplishing his assigned duties.

On 28 February 1777, William Paca married for the second time. He married well again. His bride was Ann Harrison who brought considerable wealth to the union. Ann was the daughter of Henry Harrison, a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia merchant, who had also been mayor of Philadelphia.

The couple sold the Annapolis mansion. They moved to their Wye Plantation probably to avoid the anticipated British occupation of Philadelphia. However, Ann was quite unhappy with her new life at Wye Plantation which was isolated and dull compared to the festive social life in Philadelphia. She also found herself alone much of the time, since William often traveled to York, Pennsylvania (temporary capital) as a member of Congress.

Perhaps to accommodate his wife’s desires, William decided to move back to Philadelphia in August 1777, but British troops cut off the route. It was not until the British left the city in the summer of 1778 that the Pacas were able to move back to Philadelphia.

Ann gave birth to Henry Paca in 1778. Ann never recovered from childbirth and became seriously ill. In December 1779, William returned to Philadelphia from Annapolis, where he had been attending a session of the Maryland Senate. He hoped to help Ann recover, but she died on 18 February 1780 at age 23. She was buried in Christ Church Cemetery in Philadelphia. Young Henry died in 1781.

During the interval between Mary Paca’s death in 1774 and his second marriage in 1777, William Paca fathered two illegitimate children by two different women. A daughter named Hester was born on 26 August 1775. Her mother was a free black woman, which created a scandal. Despite the scandal, Paca sent Hester to the finest boarding school in Philadelphia. He also fathered a child, Henrietta Maria, by another woman. Henrietta was born in 1776 to Sarah Joice of Annapolis. William also provided for Henrietta’s welfare and education.

Following Ann’s death, William made his primary residence at the Wye Plantation. However he built an even more grand house, Wye Hall, in the 1790s for his residence. His son, John Philemon occupied the plantation house.

William Paca had made the welfare of American soldiers a main concern of his while in the Congress. He often personally paid for supplies for the troops. After the war he supported military veterans any way he could, including legally and financially. In recognition of this, Paca was made an honorary member of the Society of the Cincinnati in 1783. This was a remarkable honor since the Society membership was reserved for revolutionary army officers.

In 1782, Paca was elected the third governor of Maryland. He was reelected in 1783 and 1784. Following the end of his third term as governor, Paca was elected to both the Senate and the House of Delegates. He chose to sit in the House since it was more responsive to the interests of the people.

Paca refused election to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 but was an anti-Federalist delegate to the Maryland Ratification Convention in April 1788. He proposed twenty-eight amendments to the Constitution designed to ensure personal freedoms and limitations of federal powers similar to the safeguards in the Maryland Constitution. Although the Federalists voted his amendments down, many of his ideas were later incorporated in the Bill of Rights.

President George Washington appointed William Paca judge of the federal district court of Maryland in Dec 1789. He held this position until his death on 13 October 1799 at Wye Hall. William Paca was initially buried at Wye Hall, but his body was later moved to the family burial ground near Wye Plantation.

I could not find any great William Paca memorials. His portrait hangs in the Maryland Senate Chamber and at least three public schools are named after him. The Paca mansion and gardens in Annapolis have been restored by the Historic Annapolis Foundation and is open to the public.

This is little remembrance. Without men like Paca, there would be no United States of America. God bless them all. We are free because of them, but as we know, freedom is fragile.

Benjamin Franklin’s famous response to Elizabeth Willing Powel’s question: “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Franklin said: “A republic, if you can keep it.

President Ronald Reagan stated: “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn’t pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected, and handed on for them to do the same, or one day we will spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children what it was once like in the United States where men were free.”