The XYZ Affair was a 1797 diplomatic incident that occurred between a United States Peace delegation and the French government when French agents demanded a substantial bribe to arrange a meeting with the French Foreign Minister. The incident inflamed American public opinion and resulted in the undeclared and limited “Quasi-War” with France. The incident had a profound effect on early American partisan politics including the hotly contested presidential election of 1800. It also played a significant role in the adoption of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

After the start of the French Revolution in 1789, France and Britain were embroiled in nearly constant war until the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. France was in disarray and was having problems financing these wars. Since their alliance with America had been a major factor in the Revolutionary War victory, they expected the US to help in their war against Britain. However, President George Washington rightfully believed that America could not afford another war and declared US neutrality.

Another irritant to the French was the 1794 Jay Treaty that was concluded to stabilize the shaky peace with Britain. The French were outraged believing the treaty was anti-French. The French were correct since the treaty contained provisions such as the one that allowed the British to seize goods from American ships sailing to France if the British paid the US.

In 1796, in retaliation to the Jay Treaty, the French began seizing American ships trading with Britain. By the end of 1798, they had seized more than 300 American merchant ships. The French also refused to receive President Washington’s newly appointed US ambassador Charles C. Pinckney. Now the Americans were outraged.

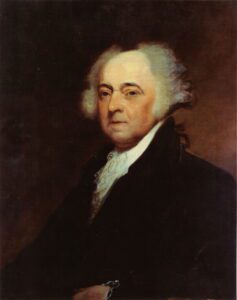

The new American President, John Adams, optimistically decided the situation could be solved by diplomacy with reasonable people working together to reach an accommodation. Adams had the right idea but also knew that the Revolutionary Government of France was completely corrupt. He selected Ambassador Pinckney, Elbridge Gerry, and John Marshall to negotiate with the French. All three envoys were accomplished American political figures. Their orders were to maintain American neutrality in the Franco-British wars, to reestablish commercial relations with France, and to avoid any commitment of financial support for France.

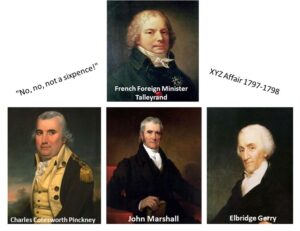

The Americans were all in France by late 1797 and were seeking an audience with the French Foreign Minister, Charles-Maurice Talleyrand. The Prime Minister, however, refused to meet with the Americans who were then forced to work through three intermediaries-Jean Conrad Hottinguer, Pierre Bellamy, and Lucien Hauteval. These intermediaries informed the Americans that certain conditions had to be met before negotiations could begin.

The conditions were: the Americans had to apologize for anti-French sentiment expressed in a 16 May Adams address to Congress, the US must make a large loan to France, must pay the claims made by American merchants for ships the French had seized, and had to pay Talleyrand 1,200,000 livres ($250,000.00). Such personal “payments” were common in French diplomacy. To make matters even worse, French victories in the ongoing war emboldened the Talleyrand government to begin threatening the American envoys.

Marshall wrote long dispatches on 22 October and 8 November explaining the situation to Secretary of State Timothy Pickering. Informal talks with the French continued during the winter of 1797-1798 with no progress. Efforts to begin serious negotiations without paying the bribes completely failed so on 24 April 1798 Marshall sailed for home, and Pinckney went to the south of France for personal reasons. Against advice, Gerry stayed in Paris in an effort to initiate negotiations. He failed and paid a high political cost for staying in France.

Back in the US, and before news of the bribery demands were known, Vice-President Thomas Jefferson believed the US had dealt with the French unfairly and he did not support Adams’ actions, particularly preparations for war. He also criticized the selection of the envoys. When Adams asked Congress to deal firmly with France and to fund a stronger military, his plans were strongly resisted by the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans.

The coded messages arrived on 4 March 1798 and the next day Adams announced to Congress that the diplomatic mission had failed. As more of the dispatches were deciphered, the Adams administration became outraged, but Adams would not immediately release the details for fear of endangering American diplomats.

On 19 March, Adams asked Congress to arm American ships, improve coastal defenses, and increase arms production. Jefferson still believed the administration was overreacting and using the incident to encourage war. He called Adams’ message to Congress “insane” and believed the wars in Europe would eventually solve all the problems.

Both parties in Congress wanted the dispatches released for their own partisan reasons and on 2 April passed a resolution for them to be published. Adams was happy to comply because he knew they would support his positions, and that the Americans were safely out of France. He replaced the names of the French agents with the letters X, Y, and Z. Obviously this is how the incident became known as the “X Y Z Affair.”

When the dispatches were released to the newspapers, Americans were enraged against France and John Adams became more popular. “Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute” became a popular Federalist slogan. The Federalists increased their majority in the House in 1798 which directly contributed to passing the “Alien & Sedition Acts.”

All this led to the undeclared “Quasi-War” with France. Although the US built up all military branches, the war was a naval conflict. This resulted in establishment of the US Department of the Navy, which gained valuable combat experience. The American military build-up and combat experience became positive factors in the US victory in the War of 1812, particularly in naval combat.

American war preparations caused Talleyrand to realize he had made a big tactical mistake and he wanted to restore normal relations. Although Congress approved renewed negotiations, the US Navy was successfully attacking French ships, particularly in the Caribbean Sea. The US also offered support to Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture (The “Father of Haiti.”)

Interestingly, in 1799 Congress passed the Logan Act, which has been in the news recently. It was passed in response to the visit of pacifist Quaker, George Logan, who negotiated with Talleyrand and announced Talleyrand’s “peaceful intentions.” The act criminalized unauthorized diplomatic negotiations but has never been enforced.

Official peace negotiations proceeded in France. Nepoleon had taken power and stabilized France. His main goal in the Americas was to re-obtain Louisiana from the Spanish, and Talleyrand, who was still Foreign Minister, wanted to end the hostilities with the US. The British were very happy with the American anti-French actions and tried to assist the US, but President Adams wanted to deescalate the situation. Adams’ position was not popular domestically, but both Adams and Talleyrand recognized that the situation was volatile and could easily escalate into full-scale war.

The negotiators negated the Revolutionary War 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France and drafted a new agreement known as the “Convention of 1800,” also known as the “Treaty of Mortefontaine,” which re-established peace. Unfortunately for John Adams, word of the agreement did not arrive in time to help him in the bitter 1800 presidential election. The new agreement did not address compensation for the seizure of American merchant ships, so Congress did not ratify a final version until 18 December 1801.

Vice President Thomas Jefferson had opposed most of President Adams’ decisions because he still had romantic memories of his early days in France. Even more importantly Jefferson wanted to be President. He reached this goal in the bitter election of 1800.

The XYZ Affair was the first big diplomatic crises the US faced and was handled in about the same way as such incidents are handled today-with confusion, hesitancy, and partisan politics. Somehow this method eventually results in a decision. The Convention of 1800 ended the US-French Alliance which was the only formal alliance of the United States. Wisely following Washington’s warning about foreign alliances, it would be nearly 150 years before the US entered into another such agreement.