Samuel Chase of Maryland was a very partisan person. He was known to use rough language and to be harsh with people, but he was a delegate to both the first and second Continental Congresses. He signed the Articles of Association, the Olive Branch Petition, and the Declaration of Independence. Following the war, he was appointed to the United States Supreme Court. He was impeached by the House of Representatives for partisanship and for being obnoxious and offensive, but the Senate did not convict him. Chase is the first, and only, Supreme Court Justice to be impeached.

Born 17 April 1741 in Somerset County, Maryland Colony, Samuel was the son of Thomas and Matilda Walker Chase. Samuel’s family had been middle-class citizens of London, England, and had emigrated to the Maryland Colony in the 1730’s. An uncle, Richard, was an Anglican priest and emigrated in 1734. Richard became a close friend and chaplain of Lord Baltimore.

Thomas Chase had graduated from both Eton and Cambridge. At Eton he earned honors in Latin and Hebrew. He studied medicine at Cambridge. He kicked around teaching and then practicing medicine and in 1739 became an Anglican Priest. Shortly after he migrated to Somerset County, Maryland and became Rector of Somerset Parish.

Samuel’s mother, Matilda Walker, was the daughter of prominent Somerset County Merchants and planters. They were also patrons of the Church of England.

Thomas and Matilda married in 1740 and they moved in with her parents. Matilda apparently died giving birth to Samuel. Despite his medical training, Thomas could not save his wife.

In February 1744, the Governor of Maryland appointed Thomas Rector of St. Paul’s Parish in Baltimore County. St. Paul’s was a large parish and included the small town of Baltimore. Rector Chase lived well beyond his means to keep up with his wealthy communicants and was in financial trouble most of his life. Samuel followed his father’s financial example.

Not much is known about Samuel Chase’s early life. He and his grandnephew, Jeremiah Chase became close friends, and both were home schooled by Rector Chase. They received a classical education. They were taught Latin, Greek, literature, and history, which was probably equivalent to a college education of the time. Samuel and Jeremiah remained friends and both became attorneys, legislators, and judges.

In 1759 Samuel moved to Annapolis, Maryland. He entered the law offices of Holland and Hall to study law. It cost around 50 Pounds Sterling to enter a law firm for training, and Samuel was strapped for money. He sped up his studies and tried to find new sources of income. There is no evidence that he found any other income.

One reason he never found new sources of income was because he had an active social life. Chase was eventually accepted into one of the local social clubs. These clubs were symbols of being a “gentleman.”

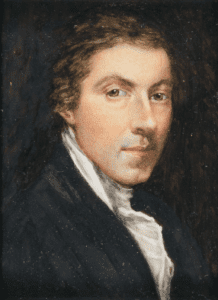

At his club, Samuel met William Paca, the son of a wealthy Harford County, Maryland family. The two developed a friendship that lasted a lifetime. They were quite different. Samuel was gregarious and impetuous. William was inclined to stay in the background and influence others with his writings. They would become important in the coming rebellion, both would sign the Declaration of Independence, and William would become Governor of Maryland.

Samuel met Ann Nancy Baldwin of Annapolis and they quickly fell in love. They were married on 2 May 1762 in Annapolis. One source said, “The match was one of love, not convenience for Samuel’s bride enhanced neither his social standing nor his material prosperity.” The couple lived on the edge of poverty until Samuel was admitted to the Bar in March 1763. They had seven children with four surviving childhood.

Also in 1762, Chase was expelled from the Forensic Club, an Annapolis debating society, for “extremely irregular and indecent” behavior.

In the early years of his law practice, Samuel had to take cases that experienced attorneys generally would not take. However, by taking these cases he built a long-lasting constituency of ordinary people (“middling sort”) who later formed his political base. He represented these people pro bono or for small fees. His efforts often allowed his clients to get back on their feet and to pay what they owed.

The strength of Chase’s constituency was shown in October 1764 when he worked with two tradesmen seeking office on the ten-member Annapolis Common Council. The members were supposed to be elected by the citizens, but the council had become a self-perpetuating body that ignored most of the city’s needs. Samuel mobilized the city’s shopkeepers and artisans to vote the two candidates into office.

In November Samuel Chase began his political career by successfully running for one of Annapolis’ seats in the Maryland General Assembly Lower House. He had mobilized the politically disaffected and his own constituency to win a highly contested, vicious, and nasty election. He had already become a prominent and powerful politician in Annapolis.

Samuel’s election coincided with Parliament’s passage of the Stamp Act. Opposition spread throughout the colonies since it was the first British attempt to directly tax them. In Maryland, Lord Baltimore saw the Stamp Act as a direct violation of the 1632 charter that promised Maryland immunity from taxation by the Crown. Lord Baltimore’s government was obligated to enforce the law but was not inclined to do so.

Patriots in Massachusetts had concluded that the Stamp Act could not be enforced if stamped paper was not available. They intimidated the person responsible for distributing the stamped paper and forced him to resign.

When the word about Massachusetts reached Maryland, a mob led by Samuel Chase on 26 August fashioned an effigy of a merchant named Zachariah Hood who was to distribute stamped paper. The treatment of the effigy left no doubt what was in store for Hood. Other such demonstrations spread throughout the Colony.

Two days later, the mob reassembled and tore down the building Hood was going to use to store the stamped paper. Hood feared for his life and fled to New York. The Royal Governor, Horatio Sharpe, transferred the stamped paper to a British warship for safe keeping.

Since no stamped paper was available, the Stamp Act could not be enforced. Business and government proceeded without the paper in defiance of the Crown.

Resistance to the Stamp Act had spawned the Sons of Liberty in some colonies and the New York Sons urged Patriots in Maryland to do the same, and they did. The Reverend Thomas Chase was a member in Baltimore Town and in Annapolis the organizers were Samuel Chase and William Paca.

In March 1766, the Stamp Act was repealed. Resistance to the Act had made Chase a prominent political figure in Maryland. He remained a member of the General Assembly until 1784. He had gained a reputation as an exceptionally hard worker.

Marylanders became increasingly anti-British, although the Tea Act did not cause the furor that it did in the north. Maryland formed a Committee of Correspondence in October 1773 and Chase became a member.

In May 1774, Parliament passed the first of a series of acts that became known as “The Intolerable Acts.” The Port of Boston was closed by the British and the other colonies saw Boston suffering because of British tyranny and rallied in support of Boston. When word of Parliament’s action reached Annapolis, Chase convened a public meeting on 25 May. He called for a boycott of all trade with Britain, which all of Maryland embraced. Maryland also called for a Continental Congress to examine the Colonies’ “relationship with Britain.”

Samuel Chase, and others, were now guilty of sedition in the eyes of the Crown. However, these Patriots surged ahead towards revolution. Chase, Paca, and others were selected to represent Maryland in the First Continental Congress. Chase arrived in Philadelphia on 3 September and began meeting delegates from other colonies. He met John Adams who became a lifelong friend.

The Congress was deeply divided between those wanting independence and those that wanted it both ways. All did agree that an armed rebellion was “out of the question.” Many in Congress believed that things could still be patched up and things could go back to normal; however, the Crown and the Patriots had reached the point of no return.

Congress compromised and called for an import boycott in December 1774 and an export boycott in September 1775 if Parliament would not compromise. Chase was opposed to any delay in the boycotts but could not carry the day. At this point, he refused to align himself with either the radicals or conservatives.

The little-known Articles of Association were passed on 20 October 1774. This act was simply a way to recognize that a boycott of trade with Britain was necessary in all 13 colonies.

The Maryland delegates found political chaos when they returned home. The ship Peggy Stewart and her cargo of tea had been burned in Annapolis Harbor on 19 October 1774. The burning of the Peggy Stewart was a powerful demonstration of the revolutionary fervor brewing in Maryland. Chase took advantage of the situation to expand his political power and to put down Tory resistance. He became the most powerful politician in Maryland.

By early 1775, the rift with Britain had worsened and Chase was determined to resist all British actions that violated colonial rights. He believed: the British “must either give up the Right of Taxation, or force obedience by the sword.”

In a 5 February letter to James Duane, a New York delegate to Congress, Samuel wrote:

“When I reflect on the enormous Influence of the Crown, the System of Corruption introduced as the Art of Government, the Venality of the Electors (the radical Source of every other Evil), the open and repeated violations, by Parliament of the Constitution. . I have not the least Dawn of Hope in the Justice, Humanity, Wisdom /or Virtue of the British Nation. I consider them as one of the most abandoned and wicked People under the Sun . . . Our Dependence must be on God and ourselves.”

The fighting at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts in April 1775 was the first battle with the British military and was a turning point to revolution. Chase called for a transfer of power from the existing colonial government to the Provincial Convention. Maryland’s government peacefully passed to the revolutionary authorities.

Samuel Chase then returned to the Second Continental Congress. On 5 July 1775 they passed the “Olive Branch Petition” which was an effort to compromise with the Crown and avert war. It was rejected by the King.

Chase was appointed to a commission of delegates that traveled to Quebec in an attempt to get the Canadians to join the colonies in a Free America Association. The group left Philadelphia on 26 March 1776. The mission failed and the group arrived back in Philadelphia on 11 June. An American military operation against Canada also failed due to a lack of Congressional support and poor leadership.

On 28 April 1776, Chase wrote to John Adams to push for Congress to give full attention to the war effort:

“Do not spend your precious Time on Debates about our Independency. In my Judgement You have no alternative between Independency and Slavery, and what American can hesitate in the Choice, but don’t harangue about it, act as if it were [independent]. Make every preparation for War, take all prudent Measures to procure Success for our Arms, and the Consequence is obvious.”

Congress was still divided on the question of independence and on 7 June 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee introduced his resolution for complete independence from Britain. This resolution forced the Congress to seriously consider independence.

Chase learned that the Maryland Provincial Convention had ordered its delegates to work for reconciliation, and to oppose independence. Samuel Chase then returned to Annapolis. During the last half of June, he and Charles Carroll visited counties throughout Maryland rousing the people to action. On 28 June, the Convention was confronted by a horde of people demanding separation from Britain. They quickly authorized Maryland’s Congressional delegates to vote for independence.

Immediately after the decision, Samuel rode the 150 miles to Philadelphia in two days. On the morning of 1 July, he informed the other Maryland delegates that they could vote for independence, but he could not stay for the vote. His wife, Ann, was seriously ill, so he returned to Annapolis to be with her. He missed the 2 July vote for independence and the formal adoption of the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776. There is no known record of Ann Chase’s death, but it was between 1776 and 1779.

Samuel returned to Congress on 17 July 1776 and on 2 August he and most of the other delegates formally signed the Declaration of Independence. During the war, he became involved with the problems of provisioning the troops, particularly Maryland troops.

For several years, Chase spent more time building up his law practice. He began accepting students into his law office. One student was William Pickney who later became Attorney General of the United States. He also helped draft a new Constitution for Maryland.

Back in Congress, Chase was active in the debate on the Articles of Confederation, which were adopted on 15 November 1777. He campaigned for the new national government to control the frontier lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, but Congress let the states retain their colonial boundaries.

In 1778, Samuel became involved in a major scandal. He tried to corner the flour market during the time Congress was authorizing the purchase of flour for the Continental Army. As a result, he lost his seat in Congress and much of his reputation. Alexander Hamilton intensely despised Chase and wrote in a New York newspaper:

“It is your lot to have the peculiar privilege of being universally despised…”

The income from Chase’s law practice was not sufficient to maintain his lifestyle, so he sought other sources. In the late 1770’s he was a member of a group that operated a saltworks. He was a partner with John Dorsey and Co, which made large purchases of grain and is what resulted in his trouble and loss of his congressional seat. He also invested in an ironworks, an unsuccessful attempt to improve navigation in the Potomac River, a Baltimore wharf, a lumberyard, and a pile driving machine. He also wanted Congress to authorize paper money during the mid-1780’s depression, which would have enriched him.

Maryland’s pre-revolution government had bought stock in the Bank of England using tax money. By 1783 the total value of the stock was about 120,000 pounds sterling, and Maryland wanted the money to reduce their war debts. The governor was William Paca, and he selected Samuel Chase to be the state’s agent. Chase sailed for England in August 1783.

The London trustees for Maryland had long relationships with Maryland’s former government and refused to release the funds. After months of wrangling, the Court of Chancery took control of the funds pending a political solution. Chase sailed back in August 1784. The settlement was not reached until 1804. Maryland received about 140,000 pounds sterling and Chase received 6,500 pounds sterling commission. However, Maryland refused to pay his expenses and he sued them. Settlement of the suit did not come until 1910.

While in England, Samuel met and married Hannah Kitty Giles, daughter of Dr. Samuel Giles of Kent Bury. They were married on 3 March 1784. The bride was “a woman of good family, sound education, and a forceful personality.” Hannah and Samuel eventually had two children.

Chase was eventually reappointed to the Congress for two years, but he rarely attended sessions and played only a minor role. However, he remained a powerful political figure in Maryland.

In 1786, Samuel and his family moved to Baltimore where he believed his law practice could make more money because the town was growing rapidly. In February Colonel John Howard, a leading Baltimore developer, gave Chase one square of ten lots near the center of the city. Chase built a large brick townhouse on one of his lots.

Howard also offered Chase another square of ten lots if Baltimore became the capital of Maryland and the government buildings were built on his land. Howard believed Chase had enough political influence to convince the Maryland legislature to make the move. Obviously, the capital of Maryland is still in Annapolis, so Howard was wrong.

Prior to the May 1787 Constitutional Convention political parties were organized. Two parties were organized-the Federalists and the Antifederalists. The Federalists believed in a strong central government and the Antifederalists believed political power should be in the states. Samuel Chase was an Antifederalist. Maryland was firmly in the Federalist camp.

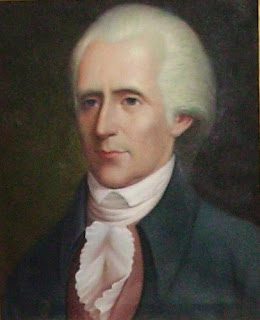

Chase, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, and William Paca all turned down appointments to the Constitutional Convention. Once the Constitution was drafted, Chase was opposed to it because he believed there was no protection of the rights of states nor individuals. Maryland’s Constitutional Convention began on 21 April 1788 and both Chase and Paca presented their reservations of the document; however, on 26 April Maryland ratified the Constitution by a vote of 63 to 11.

Chase ran for a seat in the Maryland General Assembly, but the Federalists were in power and declared sending Chase to the Assembly “would be entrusting one’s house keys to a burglar.” Chase was defeated. He was bankrupt and out of power but still had to provide for his family.

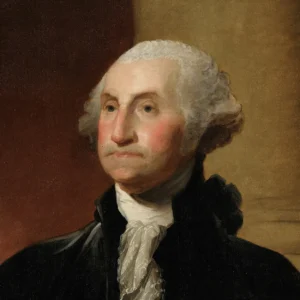

The election of Chase’s friend, George Washington, to the presidency and the 1789 passage of the Bill of Rights influenced Chase to convert to the Federalist party. He wrote President Washington asking for appointment to the Supreme Court, but Washington already had a slate of candidates. Also, he was still an Antifederalist in the eyes of most Federalists.

Maryland Governor John Howard appointed Chase to be Chief judge of the new Maryland General Court in August 1791. In December 1791 he also appointed Chase Chief Justice of the new Baltimore Court of Oyer and Terminer. This resulted in a decent income but there was a problem: an appeal from the Baltimore Court would go to the General Court and Samuel Chase would be the judge in both courts.

The French Revolution had descended into the Reign of Terror and by 1793 France and England were at war. President Washington declared American neutrality, but the British began seizing American ships trading with the French and the French were seizing American ships trading with Britain. In reaction, Congress shut down American ports with a two-month embargo on foreign trade. Baltimore, with so many idle sailors, became a violent place. Chase’s Baltimore court was a major factor in suppressing mob violence and in restoring order.

In 1792 James McHenry had become a chief advisor to President Washington. He was impressed with Chase’s “defense of order” and his conversion to the Federalist Party. He recommended Chase for a national position. On 20 January 1796 Washington was ready to nominate Chase for the Supreme Court and McHenry to be Secretary of War. Both men accepted. Chase’s appointment angered many Federalists.

The Supreme Court was still finding how it would function as an equal and separate branch among the three branches of government. By 1800, the justices’ decisions and opinions developed the court’s place, and Samuel Chase was a major contributor to this. In 1801 when John Marshall became Chief Justice, Samuel Chase became a trusted advisor.

During the early 1790’s, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had founded the Republican Party, which was a thorn in the side of the Federalists. The Alien and Sedition Act of 1798 was passed to silence the Republicans. The First Amendment was greatly bruised by the Act but survived intact.

Samuel Chase was an ardent party member in presiding over grand jury sessions and circuit court trials under the Sedition Act. He was intemperate, caustic, opinionated, and not even-handed.

Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801 and wanted to replace Federalist judges at all levels as fast as possible. He had to wait for retirements or deaths, but he was impatient and looked for a Supreme Court justice that could be impeached. He picked Chase who he already disliked.

In January 1804, House member, Virginian John Randolph, moved to establish a committee of impeachment inquiry. They recommended impeachment based on Chase’s conduct in two trials. The Articles were presented to the House but not acted on until November. Chase had asked Alexander Hamilton to be one of his attorneys, but Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr. Ironically, Burr, As Vice President would have presided over Chase’s trial in the Senate.

The Senate trial began on 2 January 1805 and lasted until 20 February. On 1 March Chase was acquitted on all counts. He returned to the Supreme Court, but he was ill, crippled, in debt, disgraced, and he sank into obscurity. He did continue to assist and advise John Marshall. Due to illness, he missed the 1807 and 1811 sessions.

By 1811, Samuel’s health prevented him from horseback riding, so he substituted a daily carriage ride through Baltimore and the surrounding area. He knew his days were numbered, so he sent for the rector of St. Paul’s and received the Holy Eucharist. On 19 June, he was totally exhausted after his carriage ride, and he knew the end was near. His physicians and rector were called and at 11:00 PM he died so quietly that his family hardly realized he was gone. His cause of death was listed as “ossification of the heart.”

Samuel Chase was given a simple funeral at St. Paul’s Church in Baltimore where his father had been rector and where he worshipped. He was buried in St. Paul’s Church cemetery. He had asked that only his name and dates of birth and death be inscribed on his tombstone.

Samuel Chase was reburied in a plot with his father, and when his wife, Kitty died, she was buried in the same plot and a new tombstone was erected.

It is not easy to describe Samuel Chase. He was domineering, caustic, overbearing, aggressive, gregarious, overwhelming in stature and voice, and he had terrible table manners. He had a florid complexion and excitement, or anger made his face even more red. He also dominated a room because he was over six feet tall and weighed about 240 pounds, which made him bigger than most men of his time. He was also highly intelligent with a sense of humor and a deep love for his family.

Samuel’s acquittal of impeachment charges firmly reinforced the Constitutional separation of powers. Had he been convicted, the future of the judiciary as a separate and equal branch of our government would have been in danger.

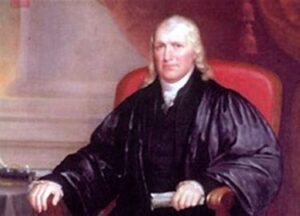

A life-sized portrait of Chase hangs in the Senate Chamber of the Maryland State House in Annapolis with portraits of the other three Maryland signers of the Declaration of Independence-William Paca, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, and Thomas Stone. Another portrait by Charles Peale hangs in the Second United States Bank in Philadelphia with the other six members of the Continental Congress that selected George Washington to command the Continental Army.

His name appears on the memorial of the Signers in Washington, DC and a World War II Liberty Ship was named in his honor.