Brittanica was kind enough to supply a very complete definition of “Tactics.” I am reprinting it here:

“tactics, in warfare, the art and science of fighting battles on land, on sea, and in the air. It is concerned with the approach to combat; the disposition of troops and other personalities; the use made of various arms, ships, or aircraft; and the execution of movements for attack or defense. The word tactics originates in the Greek taxis, meaning order, arrangement, or disposition, including the kind of disposition in which armed formations used to enter and fight battles. From this, the Greek historian Xenophon derived the term tactica, the art of drawing up soldiers in array. Likewise, the Tactica, an early 10th-century handbook probably written under the supervision of the Byzantine emperor Leo VI the Wise, dealt with formations as well as weapons and the ways of fighting with them. The term tactics fell into disuse during the European Middle Ages. It reappeared only toward the end of the 17th century, when “Tacticks” was used by English encyclopaedist John Harris to mean “the Art of Disposing any Number of Men into a proposed form of Battle.” “Further development took place toward the end of the 18th century. Until then, authors had considered fighting to be almost the sum total of war; now, however, it began to be regarded as merely one part of war. The art of fighting itself continued to carry the name tactics, whereas that of making the fight take place under the most favourable circumstances, as well as utilizing it after it had taken place, was given a new name: strategy. Since then, the terms tactics and strategy have usually marched together, but over time each has acquired both a prescriptive and a descriptive meaning. There have also been attempts to distinguish between minor tactics, the art of fighting individuals or small units, and grand tactics, a term coined about 1780 by the French military author Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte de Guibert to describe the conduct of major battles. However, this distinction seems to have been lost recently.”

The preceding is a great definition and brief history of the term, but I like to define tactics as: the planning that results in the mud and blood of war.

No matter how you define it, tactics have been used in one form or another beginning when ancient man realized that if he teamed up with others and ambushed their enemy, they had a better chance of destroying him. This was a modest beginning of combatants using battle tactics.

When early empires such as Egypt, the Hittites and others began to appear, there was a need for large armies with weapons that were more lethal. The rulers first had to win control of the people and lands. They then had to stabilize and defend it. Most of those that became militarily powerful, would eventually seek to expand their borders. These conflicts between empires led to the pursuit of better and more lethal weapons and better tactics to gain the advantage over their enemies.

The first evidence of horses in warfare was in Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. By1600 BC, improved harness and chariot designs made chariot warfare common in the Near East. Formal cavalry tactics eventually replaced the chariot because they were more flexible. Also, by the Hellenistic era, Alexander the Great neutralized chariots by opening his defensive lines and entrapping them. Then the rear ranks could overwhelm and destroy them.

The effectiveness of horses in warfare was revolutionized by the three inventions: the saddle, the stirrup, and the horse collar.

The saddle was invented about 800 BC and made the rider more stable during battle and allowed him to travel longer distances. Anyone who has ridden a horse bareback for any extended time understands the significance of this invention.

In his tome “The History of War” British Field Marshal Montgomery wrote that the invention of the stirrup in Asia in about 200 BC was the most significant military advance in history. Without stirrups the warrior had little leverage, so his sword blows were usually not lethal and when using a spear or lance, he was easily unhorsed. The invention of the stirrup alleviated these shortcomings and enormously increased the value and longevity of the mounted warrior.

Horse cavalry units were active worldwide into the early twentieth century. In Libya, Omar al-Mukhtar (known as the “Lion of the Desert”) fought the Italians, who were armed with modern weapons, to a standstill with lightly armed mounted warriors from 1911 to 1931.

Polish cavalry opposed the Nazi German invasion of Poland in 1939. They displayed extreme courage against the modern German forces but did not frontally attack German tanks despite the persistent myth to the contrary. Despite the brave Polish resistance, Poland was defeated by the Nazis, but the Polish underground was quite active and effective throughout occupation.

The invention of the “simple” horse collar in China about 400 AD revolutionized the use of horses. The collar allows horses to use their shoulders to pull loads, which is the most efficient and most effective use of their strength. Horses then replaced oxen as the primary beasts of burden because they were faster and could do twice the work in half the time. They plowed fields, and moved all types of supplies, including heavy weapons, ordnance, and men.

Elephants were used by some early Asian and African armies. The elephants were used much like today’s armor. They were terrifying to the enemy and sometimes broke the enemy’s defenses and destroyed them. However, elephants often went berserk when wounded or frightened and decimated friendly forces–an early form of friendly fire casualties.

Weapons development is a never-ending process but began with ancient man throwing rocks and using clubs. Spears in one form or another, became a staple for centuries and were used by some cavalry units through the nineteenth century.

Bows and arrows were used by early man as early as 64,000 years ago, mainly for hunting. They were first used effectively in warfare about 600 BC by mounted warriors from the Asian Steppes who fired volleys of arrows. The Greeks had never seen a person on horseback, and the first sight of these riders racing toward them while firing volleys of arrows must have been terrifying.

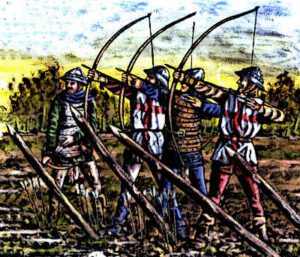

In Europe, the English became the masters of archery with the development of the powerful longbow and the requirement that all common men be proficient in its use. All able-bodied English and Welsh males starting at eight years old were required by the Crown to practice with the bow for several hours every day. The longbow had a draw weight of 90-180 pounds, with most in the upper range. English and Welsh archers developed powerful upper body strength which allowed them to fire arrows faster and longer. The effective range with a standard weight arrow was about 1,000 feet. The reload rate was eight to ten arrows per minute.

In the 1415 battle of Agincourt in France, the English commanded by King Henry V defeated a vastly superior French army by decimating the attacking French heavy cavalry and infantry by the effective use of the longbow. The English had about 3,000 archers who rained about 96,000 arrows (at only 8 arrows per man per minute) every 4 minutes on the French. The French were thrown into a confused mass of dead and wounded men, knights, and horses. This allowed the English to move in with swords, spears, battleaxes, etc. to slaughter the survivors.

Spear heads, arrowheads, and axe heads were first fabricated from stone. The advent of the metal ages (Copper Age 3200 BC-2300 BC, Bronze Age 2300 BC-700 BC and Iron Age 700 BC-1BC) and the use of those metals and simple alloys made weapons stronger, more lethal, and lighter. The development of metallurgy also allowed the development of solid body armor, helmets, and chainmail.

The Iron Age was the advent of cheaper metal which made it possible for farmers to afford iron plows and other equipment. This increased agricultural production jumpstarted economic development and prosperity. People were healthier because of improved diets. Armies were more effective because they were better fed.

As empires became healthier, larger, and more prosperous, warfare became more organized, and tactics evolved to make more effective use of animals and weapons. The great early military commanders/rulers such as Alexander the Great, Cyrus the Great, Attila the Hun, Sun Tzu and others began to appear. War between empires became more common as they all got stronger. These empires used their armies and navies to defend and expand their borders and influence. Another important use of large and strong military forces was to protect the autocratic power of monarchs.

As the centuries went on powerful and more stable nations such as France, England, Spain, China, Portugal, Italy, and Japan were organized. Ambitious and aggressive monarchs ruled these nations.

The introduction and development of firearms had more impact on warfare than any other advance for nearly a thousand years. Since firearms could be used effectively by nearly anyone, mercenaries were no longer needed to fill the ranks of armies. The ranks eventually became filled with large numbers of trained commoners. Officer ranks continued to be mostly filled with aristocrats.

Gunpowder was first produced in China in the tenth century and was initially used for fireworks, but in the eleventh century the Chinese began making crude firearms. These were handheld bamboo and metal tubes that used gunpowder to propel a small metal ball. Technology developed slowly in China and Eurasia, and it took almost 400 years to work its way to Europe. The pace of European firearms development soon left the Far East in a cloud of dust.

The first recorded use of firearms in battle by a European army was in 1364. These firearms were very crude and difficult to fire requiring the use of both hands. One hand to hold the weapon on a stand and the other to ignite the powder with a fuse.

During the fifteenth century the matchlock was invented, which was the first true shoulder fired firearm. A mechanical device on the gun moved a fuse to ignite the powder. The matchlock was replaced by the flintlock during the late 1600’s.

This flintlock used a mechanical device (hammer) holding a flint to strike a metal powder pan to create a spark that ignited the powder. The flintlock was lighter, less prone to misfires, and had a much faster reloading rate.

Fast moving light-cavalry could still overwhelm infantry units that were using flintlock muskets, so the infantry was reinforced with pikemen to defend against them. The introduction of the bayonet about 1690 eliminated the need for pikemen. The bayonet transformed the infantry into the most important branch of the early modern military.

Since the projectile fired from a firearm easily penetrated body armor, mounted and heavily armored knights became obsolete. The elimination of metal body armor resulted in armies developing distinctive cloth uniforms.

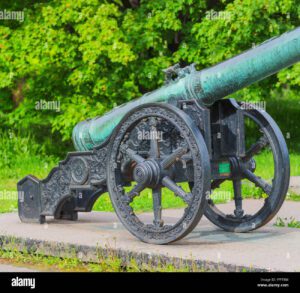

Early cannon was merely an iron tube with a hole to allow ignition of the powder, which propelled a small ball. However, the design and metallurgy of the tube advanced rapidly. The breech of the cannon is the rear where ignition occurs which results in high pressure as the ignition overcomes the inertia of the ball. This required a large diameter breech until the use of iron and iron alloys increased the strength of the metal allowing the breech diameter to be reduced which reduced weight.

The tubes were eventually mounted on strong carriages. On ships the carriage featured small wheels to allow the gun to recoil safely straight backwards and to allow the gun crew to quickly move it back to the firing position. This all had to occur in cramped quarters under enemy fire.

Ground forces mounted cannon on carriages that featured large wheels to allow easier road and battlefield travel. Initially gun crews physically moved the guns, which was notoriously slow and limited their effectiveness. The next step was to use draught animals to pull the guns and to pull caissons, which carried the gun crew and their ammunition and equipment.

The greater mobility of cannon on the battlefield allowed commanders to effectively deploy the guns more quickly. Concentrated cannon fire could decimate infantry formations and destroy fortifications. The great castles were no match for cannon fire and most city walls could be easily breached. Sieges, which in the past lasted months and even years, were completed in days or weeks in most cases.

Warfare had become too large and complex to be completely controlled by a single commander. As a result, most countries established military/civilian/ government organizations to develop and carry out military/political policy and strategy. By the eighteenth century, most, but not all, armies and navies were well trained and staffed with commoners commanded by aristocratic officers.

Eighteenth century tactics included some from earlier centuries. Earlier European wars had resulted in a large number of casualties and much devastation. This severely depleted resources and treasuries. Monarchs wanted to avoid such waste, so new tactics were developed.

Maneuver became paramount so that actual combat was often avoided for extended periods as each army jockeyed for the strongest position. When battle did occur, it was usually very brutal, but domination rather than annihilation was the goal. Once a battle ended, the retreating army was not pursued and destroyed.

These tactics did not last long because large armies meant strong nations could dominate larger areas and weaker nations. Colonial empires were being formed by the major powers and indigenous forces had to be destroyed or compromised, and the new territories had to be defended to make them safe for colonization. This required armies and navies to be even larger to defend far-flung colonial empires, and still defend the homeland.

Many seventeenth and eighteenth battle commanders were brilliant tacticians but once they closed with the enemy fighting became a melee of individual battles using personal weapons such as firearms, spears, swords, battle axes, etc.

It was obvious that the new more lethal weapons and the increased troop strength needed new and better organization and tactics. To be effective, an army must function as a team with all the parts acting in concert and supporting each other so that they can execute complex and difficult maneuvers often under fire. The armies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries adjusted rapidly.

Light cavalry was still an essential unit. It was deployed to guard the flanks of an army on the move and became the “eyes” of the commander since they also conducted reconnaissance. The rapid mobility of these mounted units allowed them to cover large areas. During battle they continued to protect the flanks but could still be used as shock troops against vulnerable points in the enemy’s lines, and to aid friendly infantry that was being overwhelmed.

Artillery units were “bulky” with heavy guns, caissons carrying ammunition and equipment, teams of horses and large crews. They had to rapidly deploy to any position selected by the commander and be quickly prepared to fire. They also had to be capable of moving to new positions on an active battleground.

The infantry had to be capable of deploying rapidly from a moving column to a fighting formation on the battlefield. They had to be ready to attack, defend, or retreat. Since Roman times, the basic infantry formation was the “square,” which put troops on four fronts with the ability to defend or attack with minimal movement. The interior of the square held troops with a variety of weapons, and replacements for the outer lines. The square supplied stability and cohesion, and the capability for rapid change.

It was obvious that extensive and concentrated troop training was needed, and all major armies soon adopted such training. The Germans adopted the most demanding and most effective training, but it was also brutal.

No army can succeed in combat without access to supplies and replacements. Bureaucracies were organized to support the armies by setting up reliable procurement of supplies, weapons, and ordnance. They had to have reliable transportation methods and schedules for delivery. This logistical tail also had to be defended.

An effective army needs a truly professional chain of command with recognizable symbols of rank. Each country developed their own version of command, but all eventually had at least some form of the following.

The overall commander needs a staff to handle the bureaucracy of the army, and he needs subordinate combat commanders for the largest maneuver units and for any independent cavalry, infantry, or artillery units. In the best organized armies, the large maneuver units were self-contained with their own infantry, cavalry, and artillery. This allowed them to be manageable in size, and to operate independently if necessary. It also made overall command and control more flexible and more reliable.

A complete battle organization also needs lower ranking officers supported by non-commissioned officers (NCOs) to provide direct leadership to the enlisted men. These men commanded the basic fighting units.

The command structures and training methods of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century armies were the forerunners of today’s military, which continues to adjust organization and command structure to meet changing threats and different environments.

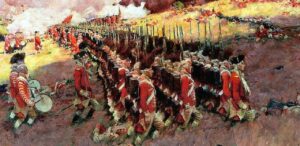

Once an army was organized, battle tactics had to be developed to best meet the enemy and to best use available weapons. The smooth-bore musket was the weapon of the infantry. They were lethal but notoriously inaccurate, so it was necessary to optimize their effectiveness.

The solution was to concentrate the musket fire into a smaller area by using a linear formation of lines (echelons) of men that slowly marched shoulder-to-shoulder towards the enemy. When they reached the effective range of their muskets (40-60 yards) they stopped. On command, the leading line leveled their muskets in unison and fired on command. They then knelt to reload while the line behind them fired. Their reload rate was about 15 seconds. If the volley fire staggered or confused the enemy, they would continue the slow march forward and sweep the enemy from the field. If the enemy stood firm, they would continue to advance shoulder-to-shoulder with bayonets fixed and engage in hand-to-hand fighting.

Defending forces often used the linear formation to maximize and concentrate their fire power.

Artillery was sometimes used to “soften” the defenders and weaken their will to fight. However, offensive artillery was often of limited value because many officers were not talented users of artillery. (American Continental General Henry Knox was a notable exception.) Cannon in defensive lines was very lethal against advancing troops.

Late in the eighteenth-century Napolean developed effective artillery tactics and his tactics have been studied and copied ever since.

Warfare was changed forever during the eighteenth century. No military commander had to sacrifice large numbers of troops in major offensive attacks where he had little control once the opposing forces closed. His army was now better organized, had better lower-level officers, improved command and control, and had well trained and committed troops armed with firearms. With this organization a field commander could coordinate and maximize the use of artillery, cavalry, and infantry.

National leaders now had a powerful tool to colonize weaker nations to expand their power, obtain scarce resources and fill their treasuries. Colonization of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas began in the fifteenth century. England became a major colonizer throughout the world including the West Indies and North America. England had a very professional and strong army, and they were gradually strengthening their naval forces. England was also blessed with excellent army and naval officers at all levels who stabilized and expanded their fighting capabilities.

The English North American colonies eventually rebelled against the mother country and the American Revolutionary War began in 1775. The Americans now had to build an army from the ground up. Luckily, many Americans, including George Washington, had served with the English army in the many wars that had been fought in the New World. This supplied a cadre of experienced officers that became the core of the new Continental Army. The colonies also had many armed militia units. Militia were the first to confront English power at Concord.

Many believe that Americans won the war because they adopted guerilla war, Indian tactics and snipers that targeted English officers. While it is true that such tactics often kept the English off balance, these tactics alone could not win the war. Washington was trying to train a conventional army to use the same tactics as the English while he was engaged in combat operations. This was an impossible situation.

Washington was not succeeding at training his army fast enough; however, in February 1778, Washington met Prussian Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben who in a letter to Washington, stated the “only object” of his “greatest ambition” was to “render your Country all the Services in my Power, and to deserve the title of the Citizen of America by fighting for the Cause of your Liberty.”

Von Steuben was appointed to the rank of Major General and Inspector General of the Continental Army. He promptly formed a model company of soldiers and trained them to march, use the bayonet, and execute orders quickly on the battlefield. In turn, this company trained all the able-bodied soldiers at Valley Forge.

Von Steuben was just what the Continental Army needed and by June 1778 he delivered to Washington a competent army that was well trained in conventional battle tactics.

The Americans used the linear formations very effectively once they were trained. However, they did introduce unconventional tactics to the battlefield. Guerilla warfare was known in Europe, but in America necessity drove its use.

The Americans used tactics they learned from fighting Indians. This included using cover and concealment, hit and run attacks, ambushes, and sniper fire. Many American irregulars had rifled muskets that were more accurate with longer effective range than smooth bores. Their downside was that reloading was much slower than smooth bores, but they were made to order for snipers.

American snipers targeted English officers as well as enlisted men. Targeting officers was considered unbecoming of civilized men by the English, but it was effective.

Unconventional tactics were used less in the north where Washington was fighting a conventional war. They were used extensively in the south where the English moved major forces in 1778.

The Continental victory at Saratoga in 1777 and the American treaty with the French in 1778 had transformed the war. The British were faced with a global conflict with France, so they changed their strategy. Rather than mounting a full-scale military campaign against the now well-trained Continental Army in the north, they decided to focus their efforts on the loyalists, who they still believed were the majority of the American population, especially in the south. Sir General Henry Clinton initially commanded the British forces in the south, but he was replaced in 1780 by Lieutenant General George Cornwallis.

The British had occupied Savannah, Georgia, in late 1778 and Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1779. They also struck a disastrous blow to General Horatio Gates’ forces at Camden, South Carolina, in August 1780. However, the British had greatly overestimated loyalist sentiment, and had underestimated the logistical problems they would encounter.

American Generals Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan commanded Continental forces in the south. They were both brilliant military leaders, but they were greatly outnumbered so they turned to guerrilla and hit-and-run warfare. General Francis Marion became famous as the “Swamp Fox” because he led such a successful guerilla campaign.

The combination of conventional and unconventional forces in the south fought the English to a standstill and interdicted their supply lines. General Cornwallis was forced to move to Yorktown, Virginia where he expected to meet an English Fleet to get reinforcements and supplies. However, a French fleet drove the British fleet away.

A very rapid concentration of American and French forces trapped Cornwallis at Yorktown, forcing him to surrender on 19 October 1781. This essentially ended the Revolutionary War fighting. The British sued for peace and the 3 September 1783 Treaty of Paris officially ended the war.

The eighteenth-century infantrymen were probably the most disciplined and best trained the world has ever seen. They fought with courage and resiliency all over the world and won vast empires for their sovereigns. The tactics they used were sound and effective. Forms of their linear tactics were used by armies through World War I.

In conclusion, tactics have a way of changing slowly and becoming politicized. This usually results in high casualties until the military and civilian leaders learn and develop new tactics or are replaced. There are many modern examples. These are just a few:

In World War I trench warfare with sporadic frontal assaults continued even though early tanks had proved their effectiveness. By World War II the Germans had proved the effectiveness of mechanized forces, air power, and airborne assaults, which set tactics for the war in Europe. However, politics prevented General Patton from taking Berlin which would have greatly changed the balance of power of the Cold War.

In the Pacific, Americans did not share intelligence about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor. In Korea, General MacArthur was not allowed to destroy the Yalu River bridges. When major American troops entered Viet Nam, the war was initially fought like WW II with large sweep operations that were ineffective against unconvential forces. Politics caused the cancellation of air cover for the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

Hopefully, we have learned from our past mistakes.