Samuel Adams, the cousin of John Adams, was a terrible businessman, but an excellent politician. He and John were early agitators for independence. Boston was a hotbed of resistance to the British, and the Adams’ led the way. Sam and John signed the Declaration of Independence. Sam served in the Continental Congress until 1781. He was also active in drafting the Massachusetts Constitution and was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts in 1789. In 1794 he was elected governor of the state and was reelected annually until 1797 when he retired for health reasons.

Born into an affluent Boston Puritan family, Samuel Adams entered this world on 27 September 1722. His father, Samuel Adams Sr. was a prominent merchant and religious leader who was also involved in local politics. His mother, Mary was the daughter of a local businessman.

Sam attended the Boston Latin School and then Harvard College. At Harvard he was introduced to the writings of John Locke an influential English philosopher and physician of the Enlightenment. Locke wrote that all people were born with certain rights that could not be taken away, and that governments exist by the consent of the people. These ideas made a powerful impression on Samuel. He wrote his 1743 Harvard master’s degree thesis on the legality of resisting British authority.

In 1748 Adams’ father died and he inherited the family business, but Sam Adams was a terrible businessman and eventually went bankrupt. He became a city tax collector but was so inept that his office came up short by thousands of pounds.

Although Sam was a public and personal business failure, he was an active and influential politician, and a persuasive writer. He became more prominent in the 1760’s when the British parliament tried to pay off debt from the Seven Years War (French and Indian War) by imposing new taxes on the colonies. Adams argued that the British were violating colonial rights because they were being taxed without representation. Adams denounced the 1765 Stamp Tax as an attempt “to destroy the liberties of America as with one blow.”

In 1765, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, a position he would hold for nine years. He also joined a secret group of activists called the “Loyal Nine.” This group evolved into an even more radical group known as the “Sons of Liberty.”

Cousin John Adams (became second President of the United States) described Samuel as a “plain, modest, and virtuous man” but that was an amazing understatement. Sam was a passionate politician, and a propagandist who often embellished the truth when he attacked British officials and policies. He authored a myriad of newspaper letters and essays over many aliases that described British policies and royal officials in the worst possible terms. He was always stirring the pot.

Sam Adams was a great political organizer. He got men elected that agreed with him, set up groups that acted as he wished, and secured passage of resolutions that he wanted.

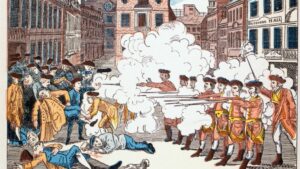

The arrival of British troops in Boston in 1768 was a gift to Sam since it gave him a very visible propaganda target. His many articles portrayed the soldiers as brutal, oppressive, and a danger to colonial wives and daughters.

On 5 March 1770, the Boston Massacre occurred when a confrontation with British soldiers resulted in the British firing into a threatening mob of colonists killing five. Following this incident, Adams led the colonials in a town meeting that demanded and secured the removal of British troops from Boston. Cousin John was a defense attorney for the British troops involved in the incident because he believed any person accused deserved legal representation.

Sam Adams had been unable to persuade Massachusetts colonists to take extreme steps during the Townshend duties crises (1767-1770). When these duties, except for tea were repealed, the anti-British ardor of the people began to dwindle, but Sam still stirred the pot by reviving old issues and finding new ones.

The next crisis was caused by Parliament passing the Tea Act of 1773, which gave the East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies. This act also reduced the duty on imported tea. The Americans would get tea at a lower price than ever; however, if they paid the duty, they would be agreeing that Parliament had the right to tax them. Tea was a staple of colonial life so the British assumed the colonists would rather pay the tax than deny themselves the pleasure of a cup of tea. They were wrong. The colonists were not fooled by Parliament’s ploy.

When the East India Company sent shipments of tea to Philadelphia and New York the ships were not allowed to dock. In Charleston, the ships were permitted to dock but their cargo was sent to a warehouse where it remained for three years until it was sold to help finance the American Revolution.

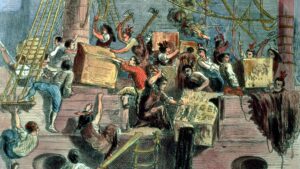

In Boston, the arrival of three tea ships ignited a furious reaction. The crisis came to a head on 16 December 1773, when about 7,000 locals milled about the wharf where the ships were docked. A mass meeting at the Old South Meeting House resolved that the ships should leave the port without payment of the duty. The Collector of Customs refused to allow the ships to leave without payment of the duty, which infuriated the locals.

That evening a group of about 200 men, some disguised as Indians, marched to the wharf, boarded the three ships, and dumped the cargos of tea into the water. This act is known as the “Boston Tea Party.” and the protesters were Sons of Liberty members. Although Sam did not take part in the incident, he undoubtedly was one of the planners.

Adams wrote that the protesters “have acted upon pure and upright principle.” Most colonists agreed, but the reaction in London was swift and harsh. In March 1774 Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts which among other measures closed the Port of Boston. The fuse that led to war had been lit in Boston and Sam Adams was a major leader of the rebellion that exploded. Also in 1774, Sam was elected to the Continental Congress where he and cousin John advocated for independence.

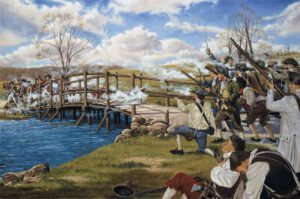

By 1775, the British authorities had grown tired of Sam Adams and his highly effective and constant agitation. In April, hardliner British Major General and Royal Governor of Massachusetts Thomas Gage led British troops from Boston to Concord to uncover ammunition caches and to capture the agitators Samuel Adams and John Hancock. American spies got wind of the plan and both men escaped, and militiamen confronted the British on Lexington green. The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the opening guns of the American Revolution.

Sam and John Adams exerted considerable influence in the Continental Congress and strongly advocated for independence. In 1776 they voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence. Afterwards Sam continued his fiery rhetoric.

Much of Sam’s rhetoric was aimed at Loyalists—Americans who continued to support the British crown. In a 1776 speech in Philadelphia, he rebuked Loyalists with these words: “If ye love wealth better than liberty, the tranquility of servitude than the animating contest of freedom-go from us in peace.” He continued: “We ask not your counsels or arms. Crouch down and lick the hands which feed you.” These were direct and harsh words.

Sam believed Loyalists were as dangerous to American liberty as British soldiers. In Massachusetts, more than 300 Loyalists were banished, and their property confiscated. After the war, Sam Adams opposed allowing Loyalists to return to Massachusetts, fearing that they would work to undermine republican government.

Sam Adams was the Massachusetts congressional delegate appointed to the committee to draft the Articles of Confederation, the plan for the colonial government. The Articles emphasized state sovereignty, which reflected Congress’ wariness of a strong central government, a concern shared by Adams.

Adams returned to Boston in 1779 to attend the state constitutional convention. He was appointed to a three-man drafting committee with his cousin John and James Bowdoin. They drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, which was amended by the convention and approved by voters in 1780.

In 1781, Sam Adams retired from the Continental Congress but remained active in Massachusetts politics. He focused on promoting virtue, which he considered essential in a republican government. If republican leaders lacked virtue, he believed, liberty was endangered. His major opponent in this campaign was his former friend John Hancock. The two men had a falling out and Sam disapproved of what he viewed as Hancock’s vanity and extravagance. Sam believed this was inappropriate in a republican leader and that Hancock was acting like an aristocrat and courting popularity. Adams favored James Bowdoin for governor and was distressed when Hancock won annual landslide victories.

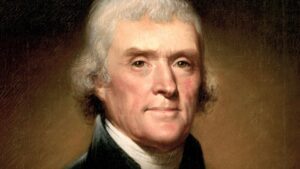

Adams’ promotion of public virtue included getting Boston to provide free public education for children, even for girls, which was controversial. Sam became one of the charter members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1780. After the Revolutionary War, he joined others, including Thomas Jefferson, in denouncing the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization of former army officers which he believed was “a stride towards an hereditary military nobility.”

Events during and following the Revolutionary War proved the Articles of Confederation were ineffective and needed to be revised. In 1787, delegates to the Philadelphia Convention did not revise the Articles, but instead authored the United States Constitution with a much stronger national government. The Constitution was sent to the states for ratification. Sam opposed it because he believed it gave too much power to the Federal Government. Proponents of the Constitution were labeled Federalists and the opponents were Anti-Federalists.

Adams was elected to the Massachusetts ratifying convention which met in January 1788. Despite his reservations, Sam rarely spoke but listened carefully to the arguments. He and John Hancock (they had reconciled) finally agreed to support the Constitution, with the agreement that amendments be added later. Even with the support of Hancock and Adams, the Massachusetts convention narrowly ratified the Constitution.

While Adams was attending the ratifying convention, his only son Samuel Adams, Jr. died at 37 years of age. The younger Adams had been an army surgeon during the Revolutionary War but had fallen ill and never fully recovered. The death was a stunning blow to his father. The younger Adams left his father the certificates that he had earned as a soldier, giving Sam and his wife unexpected financial security in their final years. They did not alter their frugal Puritan lifestyle.

Sam Adams attempted to re-enter national politics by becoming a candidate for the House of Representatives in the December 1788 election. He lost to Federalist Fisher Ames. Despite his defeat, Sam continued to work for amendments to the Constitution, a movement that led to the addition of the Bill of Rights in 1791.

In 1789, Sam was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He served in that office until Governor John Hancock’s death in 1793, when he became acting governor. The next year, he was elected governor and was elected to four more annual terms.

During the 1796 U. S. presidential election, Sam supported Thomas Jefferson for president, but his Federalist cousin John Adams won the election, with Jefferson becoming vice-president. The Adams cousins remained friends, but Sam was pleased when Jefferson defeated John in the 1800 presidential election.

Sam Adams retired from politics at the end of his term as governor in 1797. He suffered from what is believed to have been “essential tremor,” a movement disorder that made him unable to write during the last ten years of his life.

Samuel Adams died in Boston at the age of 81 on 2 October 1803. He was buried at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston. Boston’s Republican newspaper the Independent Chronicle eulogized Sam as the “Father of the American Revolution.” I believe they were correct.

Long after Sam’s death, orator Edward Everett called him “the last of the Puritans.”

A statue of Samuel Adams represents Massachusetts in the statuary hall of the US Capitol and another statue of him is in front of Faneuil Hall in Boston.

One of my favorite Sam Adams quotes is:

“I firmly believe that the benevolent Creator designed the republican Form of Government for Man.”

Samuel Adams, 14 April 1785