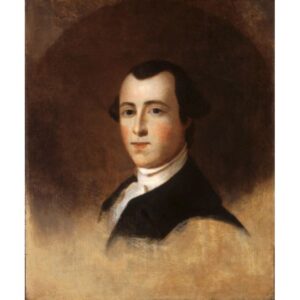

Founding Father Thomas Heyward Jr. was a successful planter, lawyer, legislator, and judge. He was an early advocate for independence from Britain and represented South Carolina in the Continental Congress where he signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. Heyward not only talked about independence, but he also fought for it as a militia artillery officer in the Continental Army. He was captured by the British and imprisoned for nearly a year.

Born on 28 July 1746 at Old House Plantation in St. Luke’s Parish (now Jasper County) in the “low country” of South Carolina, Thomas was the eldest son of Daniel and Maria Miles Heyward. The Heywards had been in America for five generations and Daniel was one of the wealthiest planters of his day. Maria was the daughter of William and Mary Butler Miles of St. Andrew Parish (Berkely County), South Carolina. Thomas was given the suffix “junior” to differentiate him from an uncle of the same name.

Daniel Heyward was a believer in the importance of education, so Thomas was provided with a classical education and some legal training locally. Daniel was also a strong loyalist devoted to the British Crown, so he sent Thomas to England to complete his legal preparation. He was admitted to the Middle Temple, Cambridge University and later was admitted to the bar in England.

During his stay in England, Thomas learned that a colonial British subject was considered inferior to native-born Englishmen and that the touted English rights did not apply equally to colonists. The prejudice was blatant and was also obvious in the Crown appointments to positions in the colonies, which went to native-born Englishmen most of the time. This prejudice convinced Thomas that the colonies should be free and independent from the mother country.

Following his education, Thomas toured Europe. He enjoyed visiting the European countries, but he found the Europeans to be indolent and haughty compared to the industry and simplicity of most Americans. Thomas was happy to leave Europe behind and return to South Carolina where he was admitted to the Charleston Bar in 1771.

Heyward began the practice of law in Charleston. His law business was successful, but he still found the time to return to Old House plantation to assist in the management of the family’s vast holdings.

In 1772 or 1773, Thomas Heyward married Elizabeth Matthews. She was the daughter of Colonel John and Sarah Gibbes Matthews. Her brother, John, became Governor of South Carolina. Thomas and Elizabeth had six children but only one survived childhood.

Thomas rose in prominence as an American patriot and became even more vocal about independence as news of British actions and patriot resistance in Massachusetts reached Charleston. Thomas’ actions and words humiliated and angered his loyalist father.

Thomas was elected to the General Assembly of South Carolina in 1772. He served until 1775 when Lord William Campbell, the last Royal Governor, dissolved the assembly and fled the country.

Heyward was elected to the first Provincial Congress in January 1775 and the Second Provincial Congress in June 1775. During the second congress, he was appointed to a committee to draft a new South Carolina constitution. The new constitution was adopted on 26 March 1776 and the congress became the state’s first General Assembly.

Thomas Heyward was elected to the First Continental Congress that met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a supporter of the Lee resolution to declare independence from England. He voted for independence on 2 July 1776 and voted to accept the final text of the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776. Later, probably on 2 August, he and the other three South Carolina delegates, Edward Rutledge, Thomas Lynch, and Arthur Middleton signed the Declaration.

Thomas Heyward’s father warned him that the British would probably hang him for his actions, but Thomas didn’t care. Luckily, Thomas and his father put aside politics and reconciled before the 11 October 1777 death of his father.

In 1778 Thomas was again elected to the South Carolina General Assembly serving until 1790. He was also elected to the Second Continental Congress. In Congress he took part in the debate on the Articles of Confederation and on 9 July 1778 he signed the final draft of the Articles. The South Carolina General Assembly appointed Thomas to the office of circuit judge.

At the end of 1778 Heyward left the Continental Congress and returned to South Carolina to help manage the family plantation and to begin his judicial duties at Charleston where he owned a home. He never returned to the Continental Congress.

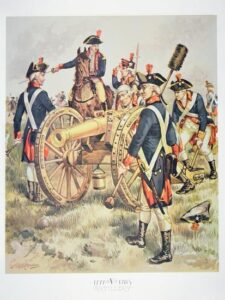

Thomas Heyward, like his fellow Declaration signer Edward Rutledge, was a member of the South Carolina militia. Heyward was a captain of the Charles Town Battalion of Artillery, which consisted of one company (one gun in SC Colonial militia). To prepare for combat, the unit was reorganized into three companies. The company commanders were Heyward, Edward Rutledge, and Anthony Toomer.

The British commanded by General Augustine Provost advanced from their base in Savannah, Georgia into the interior of Georgia where they threatened Charleston. British Major James Gardiner landed a force on Port Royal Island. American General William Moultrie’s army, including the Charles Town Battalion, marched out to oppose Gardiner.

Moultrie prevailed in the 3 February 1779 Battle of Port Royal and Gardiner withdrew. The Charles Town artillery played a pivotable role in the victory. Gardiner suffered over 50 casualties and left seven dead on the field. Moultrie suffered seven killed and 33 wounded, including Heyward who had an arm wound. Moultrie remarked that Heyward had “behaved gallantly.”

Heyward’s next major action was in April and May 1780 when British General Sir Henry Clinton and Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot laid siege to Charleston. This was the longest siege of the war and the largest battle in South Carolina, in terms of troops engaged. In recognition of his earlier performance at Port Royal, Heyward was given command of the cannon and 26 men in “Hornwork” a key fortification in the American defenses. This was a dangerous position because it was a major target of the British mortars.

The Americans put up a gallant defense but were forced to surrender on 12 May 1780. Militia officers were paroled into the city, but Heyward, Rutledge and other prominent patriots considered “ringleaders of the rebellion” were moved to St. Augustine, Florida where they were detained on prison ships. The conditions on prison ships was terrible. The constant high humidity and crowded quarters was a breeding ground for disease, particularly lung disease. During Heyward’s imprisonment, the British destroyed his plantation and confiscated much of his property. Thomas and the others were released in a prisoner exchange after about 11 months of detention.

Once released, Heyward was transported by ship to Philadelphia. During the voyage he fell overboard and nearly drowned before being rescued. His wife, Elizabeth had traveled from South Carolina to Philadelphia to be with him after his release. Sadly, Elizabeth died during childbirth on 16 August 1782. She was buried in St. Peter’s Episcopal Churchyard in Philadelphia. Thomas was devastated by her death.

Heyward returned to Charleston in 1782 to assume his duties as a judge. He helped establish much needed educational standards for acceptance to the South Carolina bar. He also served in the South Carolina General Assembly until 1790. Being very public-minded, Thomas also was a vestryman in St. Micheal’s Parish, held many commissioner positions, was a warden in Charleston’s Sixth Ward, and was a trustee of the College of Charleston.

Thomas was one of the founders of the Agricultural Society of South Carolina in 1785 and was the first president. The organization persuaded Andre Michaux, a famous French botanist, to visit South Carolina. Michaux helped introduce new crops in the area.

On 8 May 1786, Thomas married Elizabeth Savage. She was the daughter of Colonel Thomas and Mary Elliott Savage of Charleston. Colonel Savage owned the Silk Hope Plantation near Savannah, Georgia. Thomas and Elizabeth had three children that all survived childhood.

Thomas also acquired White Hall Plantation in St. Luke’s Parish in 1786 and made extensive repairs and improvements to the manor. White Hall became the home of Thomas and Elizabeth. He also owned two homes in Charleston but sold one by the time he retired.

In 1788 Thomas was a delegate to the South Carolina Constitutional Convention. He was a staunch supporter of the US Constitution. South Carolina easily ratified the document on 23 May1788, the eighth state to do so.

Thomas Heyward was a delegate to the convention that adopted a new constitution for the state in1790. Later in 1790 he retired from public life so he could manage his plantation and devote more time to his family.

President George Washington toured the southern states in 1791. The city of Charleston rented the Heyward home for use by the President during his week-long visit to the city. Washington also stopped on his trip to Savannah to spend the night with Judge Thomas and Elizabeth Heyward at White Hall. A large party was held at White Hall to honor the President.

Heyward enjoyed his retirement from public life, and he enjoyed managing the large White Hall Plantation. He resigned from the Agricultural Society in 1798 due to poor health but his health deteriorated steadily until he died on 17 April 1809. He was buried in the family cemetery at Old House Plantation. This cemetery is a designated South Carolina historic site. White Hall manor burned to the ground in 1885, and Old House Manor was burned by Union General Sherman in 1865. No images of White Hall have survived.

Thomas’ peers apparently respected and liked him. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Signer from Pennsylvania and a prominent Philadelphia physician and medical teacher, had this to say about him: “he was a firm Republican of good education and most amicable manners. He possessed an elegant political genius, which he sometimes exercised with success upon the various events of the war.”

Other than the Signers Monument in Washington, DC, I found no monuments honoring Heyward outside of South Carolina. And there is only one monument in South Carolina. The state erected a memorial stone topped with a bust of Heyward at his grave. A school was named after him, but it is under consideration to be renamed because Heyward owned slaves. Thomas Heyward gave much to the political founding and early organization of the United States and he fought to expel the British. He does not deserve to be erased.