There were many revolutions before the American revolution, but most had been smaller and unsuccessful. However, the period ca. 1775-1848 is known as the Age of Revolutions when society experienced a series of revolutions that affected nearly all areas of life: political, military, cultural, economic, and technical.

Americans had demonstrated that revolts against major powers could succeed although some historians claim that the American experience was not a revolution but was a “family squabble.” because Americans did not seek to overthrow the British government but just wanted to leave the kingdom.

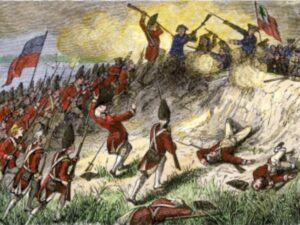

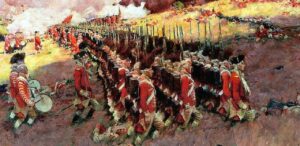

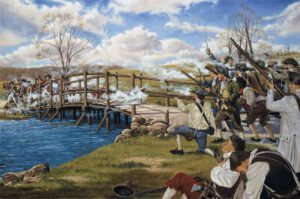

The “divorce” resulting from the “family squabble” was not peaceful and resulted in a brutal war beginning at Lexington in 1775. The patriots were assisted by Britain’s major opponents in Europe-France and Spain. Both were monarchies that wanted to weaken and destroy the British monarchy.

The French and British were historical enemies and had fought many times since William the Conqueror had won the English Crown in 1066. The French usually lost these wars. They had suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the British during the Seven Years War (French and Indian War in America). They also lost some of their North American colonies. Although the Seven Years War was costly in treasure and influence, France was still a great power in the World and was in direct competition with Britain. Both had valuable colonies worldwide.

The French saw the American Revolution as a way to get even for their Seven Years War defeat. The Seven Years War would significantly affect the rest of the eighteenth century and even affect the course of history of the western world.

Spain chose to support the Americans by allying with France, a centuries-old enemy, that had conquered many locations that were important to Spain’s security. France had also taken Louisiana. When France agreed to return Louisiana as part of an alliance, Spain entered the War on the Franco-American side.

During the Revolution Spanish forces in Florida kept the British busy protecting their southern flank. Along with their military support, Spain supplied the Americans with desperately needed arms, blankets, shoes, and currency.

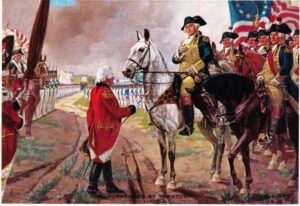

The French provided everything from uniforms to combat troops and Naval support. The Americans at Yorktown were aided by a substantial number of French troops, and the French fleet blocked British supplies and reinforcements. This battle ended major combat, and the war officially ended on 3 September 1783 with the Treaty of Paris.

The French had fought alongside the Americans and were aware of the American’s reasons for fighting and the incidents that lead up to the war. They admired the American determination to separate from Britain and to establish a new country with new concepts of freedom and democracy. Some soldiers took the American attitudes and determination back to France.

Out of the many, I have selected the four revolutions that I believe are of particular interest to our national interests.

FRENCH REVOLUTION

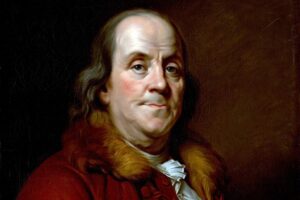

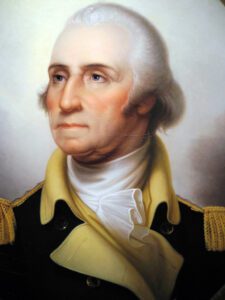

The French public was inspired by the American Declaration of Independence and admired many Americans, particularly George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson.

Patriotism in France had been on the rise before the American Revolution, but the American success demonstrated to common people that change was possible.

Aiding the American Revolution had not weakened Britain nearly as much as France had expected and it had cost them more than expected. The country was deeply in debt. The King’s treasury needed money, so taxes were raised. However, the Aristocracy was exempt from taxation and lived in luxury while the common people lived in squalor with little food. The king, Louis XVI, and his consort, Marie Antoinette, lived lavishly, which infuriated their hungry subjects.

The King had ascended to the throne in 1774 and had inherited a kingdom beset by problems. He and the aristocracy seemed to recognize the financial problem, but they thought taxes would solve the problems. They believed the people should be happy to contribute their money to bail out the kingdom.

The aristocrats believed they had control of the people and were comfortable with the situation. They did not seem to realize that France was ripe for revolution. The people knew that revolution could succeed just as the American Revolution had.

The French Aristocracy and the Royals were completely ignorant to the signs of revolution brewing in the country. The years of poor harvests, and the continued downturn of French finances resulted in a revolutionary fervor.

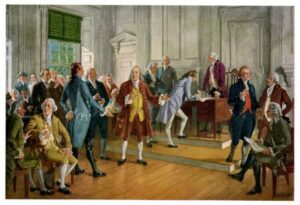

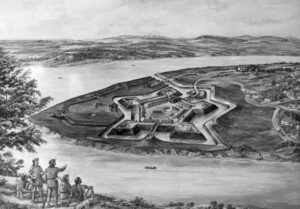

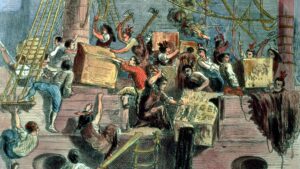

Less than six years after the end of the American Revolution, the French Revolution began. On 14 July 1789 angry and hungry citizens stormed the Bastille (old fort used as a prison.) to secure weapons and gunpowder, and to free prisoners. They succeeded and then destroyed the Bastille. Revolutionary fervor spread throughout the country. Peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and aristocrats.

In late August, the revolutionary National Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This document proclaimed philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers, but the Assembly could not agree on a constitution.

War with other European monarchies began, and in June 1793 radical factions took over the Assembly. The “Reign of Terror” began, and more radical measures were instituted, including a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity.

The King and his consort were both executed by guillotine in 1793. During a ten-month period over 17,000 “enemies of the revolution” were guillotined. Many more died in prison.

The people rebelled against The Reign of Terror, and it ended in mid-1794. The survivors adopted a more moderate phase, and a constitution was approved on 22 August 1795.

The new government was inefficient and corrupt and was maintained by the military. Most powers had been ceded to generals in the field. Napoleon Bonaparte had been a favorite, and on 9 November 1799 he staged a successful coup d’etat. He abolished the government and appointed himself France’s “First Consul.” This marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic Era.

Revolutions and uprisings large and small, successful, and unsuccessful continued unabated following the American and French Revolutions. The Americans, and the French had proved that it was possible for determined dissidents to beat the odds and defeat major military powers.

HAITIAN REVOLUTION

In 1791 the French controlled the colony of Haiti, which occupies the western third of the island of Hispaniola. The French named the colony, Saint Domingue. It was primarily populated by African slaves under the control of overseers and the French military. French colonial officers and their families represented the French government.

On the eve of the Haitian Revolution, Saint Domingue, located 4,800 nautical miles from France, was the most lucrative colony on earth. It was the world’s top producer of sugar and coffee and among the global leaders in the production of indigo, cacao and cotton. This small colony outproduced all the Spanish colonies in the Americas. One in eight people in France earned their living from Haitian trade. The population of Haiti in 1791 was about 519,000 and 87 % were slaves.

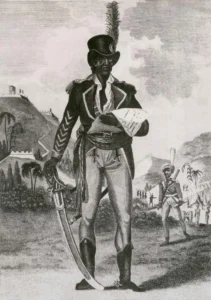

The revolution began on 14 August 1791 during a voodoo ceremony when a group of slaves pledged to fight for freedom, and they did fight. The revolution was a series of very brutal conflicts during the period 1791-1804. The revolution was also characterized by changing loyalties, racial discrimination, and serious in-fighting.

The revolutionaries were a mixture of black slaves, mulattos, and free blacks. These groups did not trust each other, and they were divided along those racial lines. The French and British played these groups against each other.

The eastern two-thirds of the island was controlled by the Spanish (became Dominican Republic). The Spanish interfered in the Revolution by supporting any faction that served their purpose at the time. The British sent troops from Jamaica to help quell the revolutionaries.

In 1793 Leger Felicite Sonthonax was sent from France to establish order. He abolished slavery but was unable to stop the uprising. In 1795, Spain ceded their part of the island to France, but war in Europe stopped the transfer.

During the late 1790s, Toussaint Louverture, a former slave, emerged as a military leader and won control of several areas of Haiti. He allied with the French, but also negotiated with the British. In 1801 he named himself “governor-general for life.”

The French sent General Charles Leclerc with experienced troops and Toussaint was forced to agree to an armistice in 1802. However, the French broke the agreement and imprisoned him in France where he died in 1803.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe lead a Black army against the French in 1802 after learning slavery was to be restored. They defeated the French and in 1803 the viscount de Rochambeau surrendered.

On 1 January 1804, Haiti was declared free and independent. Independence meant the Haitians were faced with setting up a government, but the different factions did not cooperate with each other. When they finally did manage to establish a government, it was plagued with poverty and civil unrest. Several egotists took power and lived lavishly while the people lived in squalor.

The first Constitution of a free Haiti was adopted in 1805. Haiti has adopted 21 more Constitutions since that time.

Even today Haiti is an impoverished country with a nonfunctioning government, and many Haitians risk their lives to reach the USA. The eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola is occupied by the Dominican Republic which was a Spanish possession and is prosperous and quite stable.

GREEK REVOLUTION

The Ottoman Empire was also known as the Turkish Empire. It was an imperial realm that spanned much of southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th century to the early 20th century. It also controlled parts of southeast Central Europe during the 16th to 18th centuries. It reached its peak in 1683 AD with 5.2 million square kilometers under its control.

The Ottoman Empire was Islamic controlled, but the empire held many religions and ethnic groups. The empire maintained its authority by cruelly putting down dissidents. Despite its power, bandits roamed freely in some areas. Greece was a part of the empire, but Greeks were not docile subjects. They wanted at least some form of independence. Hellenism (sense of Greek nationality) was fostered by the Greek Orthodox Church by saving and teaching the Greek language and by teaching the Greek history of democracy.

The Greek revolt began in February 1821 when a small force of Greeks entered Turkish-held Moldova, but these troops were soon defeated by the Turks. By 25 March, local revolts had broken out in the Peloponnese (today Pelopónnisos), north of the Gulf of Corinth, and on several islands. Within a year they had secured the Peloponnese, and in January 1622, they proclaimed the independence of Greece. The Turks attempted to retake this area three times from 1822 to 1824 but were repulsed each time.

The outbreak of hostilities also brought on atrocities committed by both sides. This continued until the end of the revolution but had no effect on the outcome of the war.

The Greeks were unable to consolidate or expand their area of control because of internal rivalries. In 1823 and again in 1824, Greek civil war erupted. In 1825 the civil war finally established a Greek leader; however, Egyptian troops and naval forces had been sent to assist the Turks. They wasted no time before joining forces to attack the Greeks.

With support from the Egyptian Navy, the reinforced Ottoman forces successfully invaded Peloponnese. In 1826 they captured the coastal city of Missolonghi and Athens, and the Athenian Acropolis in 1827. The Greek war for independence was about to be lost, but the situation was saved by the intervention of the major Christian European powers-Britain, France, and Russia.

The Europeans, who favored the formation of a free Greek state, offered to mediate between the Turks and Greeks. The Turks refused so the Europeans sent naval forces to Navarino and destroyed the Egyptian fleet. However, the war continued despite the Turks being crippled. Then the Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829) began which further complicated the political/military situation.

A Greek-Turkish settlement was finally reached in London on 3 February 1830. The protocol declared Greece to be an independent monarchical state under European protection. By mid-1832 borders had been established, Prince Otto of Bavaria had accepted the Greek Crown, and the Turkish Sultan recognized Greek independence. The seat of democracy, philosophy, poetry, art, and Western Civilization had been saved.

The population of the new Greek State was only about 800,000. There were about another 2.5 million Greeks in the Ottoman Empire and the Greek state worked during the next century to “redeem” those in the empire. The Greece of today was not finalized until 1947

The Greek Revolution was the first major crack in the Ottoman Empire, and it encouraged other ethnic and religious subjects to revolt. It became obvious to them that the empire was not “all-powerful.”

RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

The Russian Revolution spawned The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1917. The USSR became a powerful military nation and after World War II was the main threat to the Western powers, especially the USA. However, the USSR could not keep up with the USA spending on new weapons. The USSR was dissolved on 26 December 1991 and reverted to be Russia.

The main Russian Revolution occurred in 1917 but it was preceded by the 1905 Revolution, which has been called “The Great Dress Rehearsal” for the 1917 Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution reached Russia about 1900, which was much later than in the West. It caused a mass movement of people to cities, which resulted in overcrowding and terrible living conditions, and it created a new class of industrial workers.

A famine in 1891-1892 killed an estimated 400,000 Russians. There was a population boom at the end of the eighteenth century, a poor harvest, and a series of costly wars. Food shortages followed. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 was a disaster because Russia suffered heavy losses of men, ships, money, and prestige. Scientific advancement was virtually nonexistent in Russia.

The authority of the Russian ruler, Czar Nicholas II, was weakened by the above, and he was already weak and indecisive.

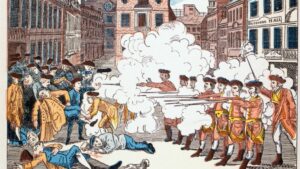

The 1905 Revolution essentially began on 22 January 1905 with the “Bloody Sunday Massacre.” Over one hundred thousand unarmed protesters were peacefully marching on the Winter Palace in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) to present the Czar with a petition on working conditions. They were attacked by the Czar’s troops and hundreds were killed or wounded.

The massacre began the 1905 Revolution. Angry workers conducted a series of crippling strikes, and farm workers and soldiers joined them. A bad omen for the government was the mutiny of the crew of the Battleship Potemkin. The military was also beginning to crack.

In response to the 1905 Revolution, The Czar promised greater freedom of speech and formation of a representative assembly (Duma). The Duma proved of no value because the Czar dissolved the body whenever they disagreed with him.

Russia entered World War I in 1914 but they were no match for Germany. The Russians suffered casualties greater than any nation in any previous war. In 1915 the Czar left Petrograd for the front to take command of the army. Another disaster because he was no military leader either.

In the Czar’s absence the Czarina Alexandra (hated woman of German ancestry) and her advisor Grigory Rasputin were so bad that Russian Nobles murdered Rasputin. There had also been rumors of a sexual relationship between Rasputin and the Czarina.

The Czar returned to Petrograd to a nation in turmoil and food shortages. The Czar had lost all respect and power and he finally abdicated on 17 March 1917 ending 300 years of Romanov rule.

The Russian Republic was born under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky, a young lawyer. His government established a liberal program of rights and opposition to violent social revolution.

Kerensky made a major mistake by continuing the Russian World War I effort which was hugely unpopular and increased food problems. Commoners believed Kerensky’s government was a continuation of Czarist programs, and violent unrest grew as peasants looted farms and food riots erupted in cities.

This was the opening that the Bolsheviks (communists) were waiting for and they overthrew the Kerensky government by taking control of Petrograd’s infrastructure and storming the Winter Palace. Vladimir Lenin was placed in charge. However, Stalin was awaiting the opportunity to take charge, which he did in 1924 following Lenin’s death. Stalin eliminated all opposition to his leadership and the Soviet Union became a major power. The Communists had executed the Czar and his family on 16 July 1918.

The fight was not over despite Communist leadership and new ideas. Civil War broke out in late 1917 between the Red Army (Communists) and the White Army (monarchists, capitalists, etc.). The war ended in 1923 with a Red Army victory. The war was characterized by cruelty and extremely high casualties of both combatants and civilians. This conflict ended any overt opposition to the Communist Government.

This is my summary of four revolutions. I believe that the first three were influenced by the American Revolution, but not the Russian Revolution. You will have to decide if I am right or wrong.

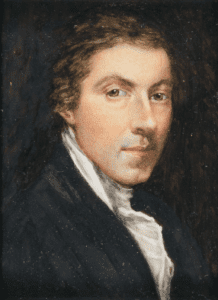

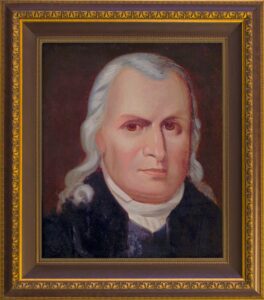

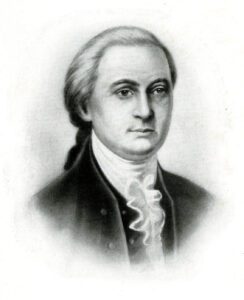

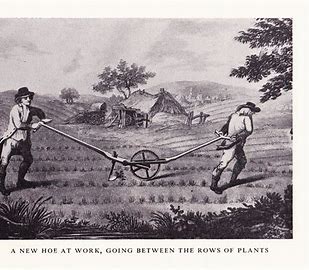

John Hart was a resident of Hunterdon County, New Jersey where he was elected to the Colonial Assembly serving for ten years. He was a New Jersey delegate to the Second Continental Congress and voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence. Afterwards, he represented Hunterdon County in the New Jersey General Assembly for many years. In December 1776 British and Hessian troops raided and looted his farm causing him to temporarily go into hiding. Hart died before the end of the Revolutionary War.

John Hart was a resident of Hunterdon County, New Jersey where he was elected to the Colonial Assembly serving for ten years. He was a New Jersey delegate to the Second Continental Congress and voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence. Afterwards, he represented Hunterdon County in the New Jersey General Assembly for many years. In December 1776 British and Hessian troops raided and looted his farm causing him to temporarily go into hiding. Hart died before the end of the Revolutionary War.