The French and Indian War is the fourth and last in the series I am reporting on, and it is the most important because it actually accomplished things. First it resulted in expansion of the British colonies to the Mississippi River and included the acquisition of Florida. Real borders were established. The French were defeated and lost their North American colonies, which removed a threat to the British colonies. This war gave combat leadership experience to many colonial officers including George Washington. These officers would be needed soon because England levied new taxes on the colonies to help pay for the war which was a factor that helped precipitate the American Revolutionary War

The French and Indian War was once again the American theater of a European War-the Seven Years’ War. However, most Americans view it as a singular conflict that stands alone. In British America, wars were often named after the sitting monarch, but there had been a King George’s War in the 1740’s during the reign of King George II. King George III was on the throne, so Americans named the war after their opponents.

The French colonial population was only about 75,000, which were mostly in the St. Lawrence River Valley. The British numbered about 1.5 million mainly along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia to Georgia. Colonists were gradually moving west. Many were moving into the frontier which was dominated by Indians and where both Briton and France claimed ownership.

Most of the fighting during the French and Indian War took place along the frontiers between New France and the British colonies from Virginia in the south to Newfoundland in the north. There were few regular army troops in North America at the outset of the war but that changed.

Indians once again took sides in an effort to get a better deal from the expanding Europeans. These alliances tended to be somewhat sporadic depending on the situation. The Iroquois, Catawba and Cherokee were allied with the British colonists. The Wabanaki Confederacy, Algonquin, Lenape. Ottawa, Shawnee, and Wyandot (Huron) were allied with the French colonists.

Although the French and Indian War officially began in 1754, there was always low-level but deadly conflict between French and British colonists and between colonists and Indians. In the years leading up to the war, the conflict was becoming even more intense and more lethal.

The New France governor became concerned about the British incursion and expanding influence in the Ohio Territory so in June 1747 he commissioned a military expedition into the area. The expedition consisted of 200 French troops and 30 Indians and was commanded by Pierre-Joseph Celeron. It was to be a show of force to impress the Indians and to discourage any Indian cooperation with the British.

Celeron’s force moved out in June 1749 and covered about 3,000 miles ending up at the site of present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The expedition was a failure. The Indians told Celeron they owned the Ohio territory and would trade with whoever they wanted to. Celeron even threatened the Miami chief, “Old Briton” but the chief ignored him.

Celeron’s expedition returned in November 1749 but was preceded by the pessimistic information. This information made its way to London and Paris, and both proposed actions to be taken. Massachusetts Governor William Shirley stated that British colonists would not be safe as long as the French were present.

The New France governor died on 17 March 1752 and was temporarily replaced by Charles le Moyne de Longueuil. His permanent replacement, Marquis Duquesne would arrive later,

The continued British activity in the Ohio Territory convinced Longueuil to organize another expedition to punish the Miami tribe for trading with the British. The expedition would consist of 300 men, including French-Canadians and Ottawa warriors. On 21 June 1752 they attacked the trading center at Pickawillany capturing three traders and killing 14 Miami’s including Old Briton who was ritually cannibalized.

The next French move was to build and garrison forts in Ohio Territory in 1753. They established Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie’s south shore, (near present day Erie, Pennsylvania) and Fort Le Boeuf (near present day Waterford, Pennsylvania). They also drove off or captured British traders. The British response was not adequate to satisfy their Indian allies. Mohawk Chief Hendrick declared that the long friendly relationship with Iroquois Confederacy was broken.

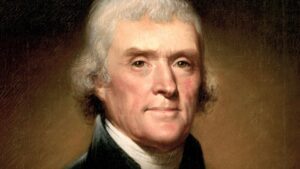

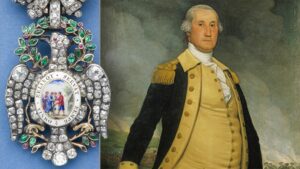

Meanwhile, Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie stood to lose a considerable sum of money if the French prevailed. In October 1753 he sent 21-year-old Major George Washington of the Virginia Regiment with a small party to warn the French to leave territory that Virginia claimed. Washington met over dinner with the French commander of Fort Le Boeuf and presented him with a letter from the governor. Of course the French declined to withdraw.

Washington arrived back in Williamsburg on 16 January 1754. In addition to delivering the French refusal to withdraw, Washington provided intelligence on French military preparations. Dinwiddie had already dispatched 40 men commanded by Captain William Trent to the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers to construct a fort before the French could. A French force of 500 men arrived on 16 April. They allowed the small British force to withdraw and even purchased their construction tools to build what became Fort Duquesne.

Governor Dinwiddie ordered Washington to take a larger force to assist Trent. Washington learned of Trent’s retreat while enroute but continued toward Fort Duquesne. Twelve Mingo warriors joined Washington increasing his force to 52. Washington ambushed a scouting party of 40 Canadiens (French colonists of New France) on 28 May1754 killing “many.” This clash became known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen and is considered to be the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

Washington withdrew a few miles and established Fort Necessity which was attacked on 3 July. Washington was forced to surrender but negotiated a withdrawal under arms. The French force had included Shawnee, Delaware and Mingo warriors.

News of the two battles soon reached Europe. The British government decided to send an army expedition to “dislodge the French.” Major General Edward Braddock was assigned to command. The French got word of the British plans and Louis XV dispatched six regiments to New France commanded by Baron Dieskau.

A British fleet set out in February 1755 intending to blockade French ports, but the French had acted quickly, and their fleet had already sailed. British Admiral Edward Hawke detached a fast squadron to North America in an unsuccessful attempt to intercept the French.

In a second British naval action Admiral Boscawen fired on the French ship Alcide on 8 June 1755, capturing her and two troop ships. The British continued harassing French shipping in 1755 by seizing ships and capturing seamen.

Once General Braddock arrived in the colonies, he developed an overly ambitious 1755 campaign. I think he believed he could win the war quickly and easily. Braddock was to attack Fort Duquesne; Governor William Shirley was to fortify Fort Oswego and to attack Fort Niagara; Sir William Johnson was to capture Fort St. Frederic at Crown Point, New York; and Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton was to capture Fort Beausejour to the east on the frontier between Nova Scotia and Acadia.

Braddock moved out in June commanding a force of 1,500 Army troops and provincial militia. George Washington was one of his aides. The expedition was a disaster. French regulars, Canadian militia, and Indian warriors ambushed and crushed Braddock’s column. Braddock ordered a retreat, but he was killed and about 1,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded. George Washington and Thomas Gage organized the retreat to Virginia. (Washington and Gage would be opponents in the American Revolutionary War.)

Governor Shirley had no experience commanding large units and was bogged down with logistical problems in his efforts to fortify Fort Oswego. Shirley learned that the French were preparing to attack Oswego when he moved to attack Fort Niagara. He responded by leaving garrisons at Oswego, Fort Bull, and Fort William Henry. He cached supplies at Fort Bull for a future attack on Fort Niagara.

Sir William Johnson was well organized, and the French saw him as a significant threat. In response the French acted to tighten their supply lines in the Ohio valley and sent a senior officer (Baron Dieskau) to take command of the defense of Frontenac and Fort St. Frederic. Dieskau wanted to attack Johnson at Fort Edward, but Johnson had estalished strong defenses.

Johnson and Dieskau clashed on 8 September between Fort Edward and Fort William Henry in the Battle of Lake George. They were nearly evenly matched, about 1,500 men each. This battle was a series of well-placed ambushes, a few frontal attacks, good tactical moves by both sides, and excellent use of three cannon by the British. Casualties were close to even, both about 300 killed or wounded. Baron Dieskau was severely wounded personally leading an assault.

Tactically, the British carried the day in this hard-fought battle. Johnson withdrew to Fort William Henry and the French to Ticonderoga Point where they constructed Fort Carillon (later Fort Ticonderoga). The British had unceremoniously thrown the bodies of French soldiers killed in the battle into a nearby pond which today is still known as “Bloody Pond.”

Colonel Monckton captured Fort Beausejour in June 1755, which was the only clear British victory. This also interdicted the French land route for reinforcements and supplies to Louisbourg, which isolated the fort. The governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence ordered the deportation of all French-speaking persons from the area. Monckton’s forces and some of Roger’s Rangers forcibly removed thousands of Acadians. They ran down those who resisted and sometimes committed atrocities.

Following the death of Braddock, William Shirley assumed command of British forces in North America. Shirley proposed an ambitious 1756 campaign, but his plans did not receive enough backing and were dropped.

Shirley was replaced in January 1756 by Lord Loudoun with Major General James Abercrombie as his second in command. Neither had much campaign experience but in May the French sent three very experienced officers and regular army reinforcements to New France. Major General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm was commander and Chevalier de Levis was his deputy. They were accompanied by Colonel Francois-Charles de Bourlamaque. All three were veterans of the War of Austrian Succession.

On 18 May 1756, Britain formally declared war on France, which brought the war to Europe where it was known as the Seven Years’ War. American and French colonists, and British and French regulars fought in North America for two years before the Seven Years’ War officially began.

French Governor Vaudreuil had ambitions to become French commander in chief, so he acted during the 1756 winter before reinforcements arrived. He ordered an attack on the weak British supply chain. His forces attacked and destroyed Fort Bull along with large quantities of supplies including 45,000 pounds of powder. The Vaudreuil initiative set back any British hopes for campaigns on Lake Ontario and endangered Fort Oswego. The French also continued their active and successful efforts to persuade Indians in the Ohio valley to raid British frontier settlements.

The new British command did not arrive until July, and they were slow to act. Montcalm took advantage of the British inertia. Montcalm was not cautious and executed a strategic feint that completely fooled the British. He moved his headquarters to Ticonderoga seemingly to attack along Lake George, which pinned down Abercrombie in Albany. Montcalm then slipped away and led a successful attack on Fort Oswego. Montcalm did not allow the Indians in his command to strip prisoners of their personal effects, which angered the Indians.

Cautious British commander Loudoun planned to attack Quebec in 1757. He left a sizable force at Fort William Henry to distract Montcalm while he prepared for the attack on Quebec; however, the Secretary of State for the colonies, William Pitt, ordered him to attack the Fort at Louisbourg first. This expedition was delayed until August when they were prepared to sail from Halifax, Nova Scotia. However, French ships had escaped the British blockade of France and awaited Loudoun at Louisbourg with a fleet that outnumbered the British. Faced with this, Loudoun returned to New York.

The French were also campaigning against Fort William Henry during 1757 while the British were being cautious. In January French irregulars ambushed British rangers near Ticonderoga. In February, they crossed frozen Lake George to William Henry and destroyed storehouses and buildings outside the main fortifications. Montcalm with 7,000 troops laid siege to the fort in early August. Fort commander Lieutenant Colonel George Monro capitulated with an agreement to withdraw under parole (Retain weapons and flags with promise not to fight against the army granting the parole).

When Monro withdrew his column consisted of his troops, Indian allies, and civilians. Some of Montcalm’s Indian allies who were still angry about being denied loot at Oswego, attacked Monro’s column killing and capturing several hundred men, women, children, and slaves.

The aftermath of this siege apparently contributed to the transmission of smallpox to remote Indian tribes. Some Indians from west of the Mississippi River reportedly had traveled east to fight in the war and then returned to their home tribes. Some historians believe this explains early infection in the west.

Fortunes changed in 1758. The blockade of France was limiting the supplies reaching New France. To make matters worse, the 1757 harvest was poor, the winter was hard, and there was a corrupt supply official involved. Also, the massive outbreak of smallpox among the western tribes limited trade.

Malcolm dedicated his limited resources to defending the St. Lawrence, particularly Carillon, Quebec, and Louisbourg. Vaudreuil unsuccessfully argued for raiding tactics that had worked well in past years.

British failures in North America combined with failures in the European theater led to the fall of Prime Minister Newcastle and his military advisor the Duke of Cumberland. Newcastle then joined in an uneasy partnership with Pitt, but Pitt dominated military planning. Pitt’s plan for 1758 was primarily developed by Loudoun who had been replaced by Abercrombie as commander in chief after the failures of 1757.

William Pitt was a visionary who saw that winning the French and Indian War should result in total British control of North America and be part of a British empire. This led Pitt to be very aggressive.

Pitt’s plan called for three major expeditions involving large numbers of regular troops supported by militias and aimed at the heartland of New France. Two of these were successful.

In the September-October period, 6,000 men led by General John Forbes was sent to drive the French out of the Ohio Territory. The French withdrew from Fort Duquesne which left the British in control of the Ohio River Valley.

Jeffry Amherst led the expedition against the French fortress at Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. Amherst lay siege to the fort and the French capitulated six weeks later. This was a bittersweet victory because the British had captured this fort during King George’s War. The peace treaty ending that war called for the British to return the fort to the French, which had enraged the British colonists.

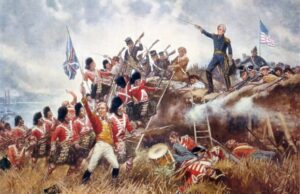

The third expedition led by Abercrombie moved to Fort Carillon with 18,000 regulars, militia and Indians. The French engaged them outside the walls of the fort with only 3 ,600 men. The British force even met the axiom that you need a force ratio of five to one to successfully assault a fortified position so it should have been an easy victory. Instead, the battle was a total disaster. The French soundly defeated the British in the Battle of Carillon.

Abercrombie withdrew, but he did salvage something from the disaster by sending Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet on an expedition that destroyed Fort Frontenac. He also destroyed caches of supplies destined for New France’s western forts and furs destined for Europe.

Abercrombie was recalled and replaced by Major General Jeffery Amherst.

The French had struggled in most theaters during 1758. They had a new foreign minister, duc de Choiseul who decided to focus on an invasion of Britain to draw British resources away from North America and the European mainland. The invasion failed militarily and politically.

Meanwhile Pitt was planning major campaigns against New France, and he sent funds to Britain’s main foe in Europe, Prussia. Also, the French Navy lost two naval battles in 1759–Lagos and Quiberon Bay. On the plus side, some French supply ships were able to evade the British blockade.

The British were campaigning in the northwest Canadian frontier to isolate French frontier forts to the west and south. The British had committed adequate men, ordnance, and materiel and were, with a few exceptions, essentially unstoppable. They were overwhelming the French. They captured Fort Ticonderoga (French called it Carillon) and Fort Niagara. They also defeated the French at the Thousand Islands by capturing Fort Levis in the summer of 1759.

The most pivotal battle was fought in September when after a hard fight British forces commanded by James Wolfe defeated Montcalm in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Both commanders were killed in this battle which resulted in the capitulation of Quebec. This was a big blow to the French, and in April 1760 the French attempted to retake Quebec. Francois Gaston de Levis led this attempt and although he won the Battle of Sainte-Foy, his siege of Quebec failed when British ships arrived to relieve the garrison. After de Levis retreated the British Navy scored a victory near the Restigouche River in New France, which interdicted supplies meant for Levis army.

In July, Jeffrey Amherst led about 18,000 men in a three-pronged attack on Montreal. The three columns converged on the city and surrounded it in September after eliminating all French resistance along the way. Amherst laid a tight siege against Montreal. There many desertions, including Indian warriors, from the city. On 8 September 1760, de Levis and Marquis de Vaudreuil reluctantly signed the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal. The fall of Quebec and Montreal essentially completed the total conquest of New France by the British.

Governor Vaudreuil and General Amherst negotiated a deal in Montreal in September that any French residents who chose to remain in the colony would be free to worship in their Roman Catholic tradition, to own property, and to remain undisturbed in their homes. This agreement did not last long because of the British Protestant colonist’s distrust of “popery,”

Most of the fighting in North America ended in 1760 but continued in Europe between Britain and France. The main exception was the surprise French seizure of St. John’s Newfoundland. General Amherst dispatched a force commanded by his nephew William Amherst. They regained control of Newfoundland after the Battle of Signal Hill in September 1762.

Once fighting ended, the British provided medical treatment for sick and wounded French soldiers. French regular troops were returned to France on British ships if they agreed not to serve again in the “present war.”

Many British regular troops stationed in North America were reassigned to the West Indies where they captured French Martinique. They also captured Spanish Havana when Spain joined the conflict on the side of France.

The French and Indian War and the Seven Years War officially ended on 10 February 1763 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. France ceded all its North American possessions east of the Mississippi River to Britain except for two small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and fishing rights in the area. They recovered their lost Caribbean possessions. Spain traded Florida to regain Havana. The Spanish also gained Louisiana, including New Orleans, Britain and Spain agreed the Mississippi River would be open to vessels of all nations.

The French and Indian War added considerable land area to the British colonies and finally established and stabilized borders. It also eliminated a hostile and aggressive enemy from those borders.

In the wake of the French and Indian War, the Crown believed the colonists should help pay for the war and help pay for and house British troops assigned to protect the colonies. Colonial militia had provided troops for the war, and many believed the British troops were no longer needed.

The Crown levied new taxes on the colonies. They were met with considerable resistance, but the British went on to pass the Intolerable Acts which infuriated the colonists even more. This was an irresistible force meeting an immovable object and led to the American Revolution.

One good result of the French and Indian War was that colonial militias had proliferated and were better trained and better armed, and many had combat experience. Also, there was a whole generation of combat experienced colonial officers. Frontier Americans produced the first unconventional warfare military units with skills that were instrumental in future wars.

The French and Indian War is ingrained in the American mind because of What it accomplished and for all the legends and literature that it spawned. The best known is the “Last of the Mohicans” by James Fenimore Cooper whose book is fictional but contains many facts. If you read the book, which generations of us have, or seen the movie you will recognize Monro’s retreat from Fort William Henry and the massacre that followed. Many towns and villages still commemorate French and Indian battles and have local museums containing artifacts from that war. ilur