Alexander Hamilton had the dubious honor of having the first sexual affair of a married American politician to become public. He had an affair with a young married woman, Maria Reynolds, whose husband blackmailed him. Hamilton publicly admitted to the affair after his political enemies accused him of financial corruption during his tenure as Secretary of the Treasury. The scandal lead to quarrels and near duels involving two of the country’s leading statesmen and was a principal factor in the struggle between the Federalists and Antifederalists.

According to Hamilton, in the summer of 1791, he was with his family in Philadelphia when a young woman called at the door and wished to speak to him in private. Hamilton agreed, and when in private, the woman identified herself as Maria Lewis Reynolds of New York. She claimed that her husband, James, had for a long time treated her cruelly and now had left her and their young daughter for another woman. She claimed she had no means to return to New York and appealed to “Colonel Hamilton to assist a woman in despair.”

Hamilton told Maria that he was “disposed” to help her but that the time was “inconvenient.” He then asked if he could send money to her place of residence or personally deliver it. Maria must have said that was acceptable. She probably encouraged a personal delivery because that evening Hamilton traveled to her rooming house with a thirty-dollar bank note in his pocket.

There are few physical descriptions of Maria Reynolds. An acquaintance of Hamilton’s said, “her innocent Countenance appeared to show an innocent Heart.” Hamilton called her “Beauty in distress” and “a pretty woman.” Some alleged she was very emotional and given to weeping. She must have been pretty enough for Hamilton to willingly walk into an obvious trap of seduction.

When Hamilton arrived at the rooming house Maria escorted him to her bedroom where Hamilton gave her the money. He said, “Some conversation ensued from which it was quickly apparent that other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable.” Hamilton was being seduced and was very willing because the two quickly ended up in bed beginning a year-long affair that caused a political scandal of stunning proportions.

Politically Hamilton was a Federalist, and he was quite busy during the summer and fall of 1791, the early months of George Washington’s first term. He was Secretary of the Treasury and Customs and was also trying to drive the Antifederalist Thomas Jefferson out of the Cabinet. He was writing scathing articles under aliases about Jefferson’s followers.

On the business side, Hamilton was preparing his fourth of five Treasury Reports on Manufactures, which when all were enacted replaced near worthless currency, funded a debt of about 75 million dollars, restored credit at home and abroad, created a national banking system, and laid the groundwork for an industrial economy with a powerful central government. All of this was bitterly opposed by Jefferson’s Antifederalist party.

The demands of his office were arduous and must have taken a great deal of time, but Hamilton always found time for Maria. He often met her at his home since his wife, Elizabeth had taken the children to visit her father in Albany, New York. Using his home for their trysts probably meant the secret was no longer secret.

Hamilton met Maria’s husband, James Reynolds because Reynolds claimed he had information on misconduct in the Treasury. Hamilton found the information to be of minor importance. Later Reynolds applied for a job in the Treasury Department, but he was turned down. Reynolds knew about his wife’s relationship with Hamilton and encouraged it because he planned to blackmail Hamilton.

Hamilton continued the affair despite writing that he wanted to end it. He wrote “…. her conduct made it extremely difficult to disentangle myself.” He continued: “My sensibility, perhaps my vanity admitted the possibility of real fondness….” Obviously, Hamilton was conflicted but kept the affair active. Thirty-four-year-old Alexander Hamilton’s hormones were raging like a teenager.

The plot thickened on 15 December 1791 when Hamilton received two letters—one from Maria and one from her husband. Maria was telling him that her husband had discovered her infidelity, and that he was threatening to inform Mrs. Hamilton if his letter was not answered. She insisted that Hamilton not respond to her husband. However, she begged Hamilton to visit her right away because she was alone, and she felt more for him than herself.

James Reynolds wrote an “injured husband” letter saying Hamilton was not a friend and had taken advantage of his wife. After the litany of wounded honor, he pointed out that Mrs. Hamilton did not know of the affair. He then insisted on meeting with Hamilton.

After several meetings and an exchange of letters James Reynolds decided that money would satisfy his wounded honor. Most men found satisfaction on the dueling field. He demanded one thousand dollars with the promise to leave town with his daughter leaving Maria to Hamilton. The money was paid in two installments on 22 December and on 3 January 1792, but Hamilton did not immediately resume his visits to Maria.

Of course, James Reynolds did not leave town because he planned to continue extorting money. To convince Hamilton to keep visiting Maria, he wrote Hamilton to say he would have no objections to him visiting Maria as a friend to “both of them.” Hamilton did not resume his visits until Maria begged him to visit at least one more time.

Hamilton visited “once” and then was hooked again and resumed regular visits. This was what James Reynolds wanted and he began demands for what he called “loans,” which Hamilton paid. In March James again encouraged Hamilton’s visits, but in May 1792 he forbade Hamilton to see his wife again.

Hamilton had finally realized that both Reynold’s were involved in extorting money from him. However, he continued visiting Maria through mid-August when he finally complied with James Reynolds’ request and cut off all contact with both of them. Hamilton had paid Reynolds a total of about $1,300 dollars (about $25,000 today), which was about a third of his annual income. Hamilton mistakenly believed that he had heard the last of this affair.

In November 1792, James Reynolds and Jacob Clingman were jailed for participating in a swindle involving back pay for Revolutionary War veterans using records obtained by a coconspirator in the Treasury Department. In an effort to avoid punishment, Clingman revealed he had knowledge of impropriety and corruption by Alexander Hamilton and insinuated that Hamilton was involved in their swindle. He brought his accusations to the attention of Federalist Frederick A. Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania. Although he considered Reynolds to be a “rascal” he passed the information to Senator James Monroe and Congressman Abraham Venable, both Virginians and both Antifederalists.

The three men interviewed James Reynolds and Maria Reynolds. James provided information on the affair knowing that Hamilton would have to admit to the affair or falsely admit to complicity in the swindle. Maria presented herself as a “victim” of the powerful Hamilton and provided letters that seemed to prove that he had used public funds for private gain. She impugned Hamilton’s character and reputation during the interview.

After the interviews, they confronted Hamilton. They said they had uncovered “a very improper connection” between him and James Reynolds. With his friend Oliver Wolcott by his side, Hamilton confessed to adultery, infidelity, and submission to blackmail, but denied any dishonesty as a public official. He held nothing back and gave a full and detailed account of his relationship with James and Maria Reynolds.

Hamilton was candid, and although they were shocked by his indiscretion, the three congressmen were convinced he was innocent of the accusations. They wrote and signed a report to themselves, sealed the documents and agreed to keep it all secret. Hamilton made his own record of the meeting and asked for copies of all the documents from the congressmen. They complied and the copies were made by Antifederalist John Beckley, Clerk of the House of Representatives. Unfortunately for Hamilton, Beckley also made copies for his files.

In 1793 Hamilton retired to private law practice in New York to spend more time with his wife and five children. He also served as an unofficial adviser to his former boss, President Washington. His life was happy and relaxed. However, in 1797 the Federalists removed John Beckley from his post in the House. Beckley was not pleased and turned over the Hamilton papers to James T. Callender an especially unscrupulous journalist.

Callender was a Scotsman driven from England for literary excesses. He migrated to America and became a political pamphleteer under the aegis of Thomas Jefferson. He ran the Hamilton story in two pamphlets, the first published in June 1797. He included all the documents the Congressmen had prepared, and he opined that Hamilton had used Reynolds and others in his speculation of government securities. He also declared Hamilton had forced James Reynolds to flee the area.

Hamilton quickly published a denial in a Federalist newspaper and declared that the three Congressmen with Wolcott as a witness decided the charges were false. He also requested that the three quickly provide a declaration confirming their findings. He suspected that Monroe was responsible for the leak partly because Callender lavished praise on Monroe.

Muhlenberg and Venable were preparing the requested declarations, but Monroe had just returned from France and had not yet followed suit. Hamilton did not trust Monroe and demanded a personal meeting with him.

The meeting was attended by Hamilton accompanied by John B. Church and Monroe with Congressman David Gelston who recorded the meeting. Hamilton was agitated and would not accept Monroe’s ignorance of the Callender pamphlet. Monroe resented being called a liar and the confrontation escalated to them racing to a duel. A duel was avoided by the intercession of Church and Gelston.

Shortly after the Monroe meeting, Hamilton read Callender’s second installment and found in it shocking documents he had not seen. One was Monroe’s interview with Clingman who charged that Hamilton had concocted the story and forged the letters to cover his own wrongdoing. Hamilton confronted Monroe by letter and again the situation escalated to them heading for a duel. This duel was averted by the efforts of Aaron Burr. Hamilton held a grudge against Monroe for the rest of his life.

Hamilton announced he would defend his honor by explaining all in a pamphlet. His friends pleaded with him, believing it could only harm his party, his family and himself. His friends suggested silence believing the matter would eventually blow over.

Hamilton ignored all the advice because he felt his honor and reputation as an incorruptible public servant was at stake. Most believed in his innocence, but that was not enough for him. He needed to remain silent, but he felt that he had to speak out to convince everybody of his innocence.

The Hamilton 95-page pamphlet called “Observations on Certain Documents” was published on 25 August 1797 and was later known as the “Reynolds Pamphlet.” He denied all charges of corruption and tried to prove it through a detailed account of his trysts with Maria Reynolds and the blackmail by her husband. The account of the sexual affair was exceptionally explicit for the time. Most of his friends believed he had degraded himself and scandalized his family in his effort to clear his name.

The publication made Hamilton appear immoral and weak-a man who would risk all for the affections of another woman and who would pay blackmail to hide it. Many saw Maria as an innocent that was taken advantage of by a powerful man. However, James Reynolds’ blackmail letters dispelled any suggestion of Hamilton’s involvement in the Reynolds-Clingman swindle.

Publication of the details of Hamilton’s sexual relationship with Maria was humiliating for his wife, Elizabeth. With no consideration for her feelings and reputation, one newspaper wrote that she must have been just as “wicked” to have such a husband. By all accounts Elizabeth forgave her husband and after his death spent the rest of her life trying to undo the damage to his reputation. She also shared his animosity towards Monroe and rejected Monroe’s effort at reconciliation shortly before his death on 4 July 1831.

Jefferson and other Antifederalists were delighted with the revelations and declared the document was further proof of Hamilton’s guilt and unworthiness for public office. As an ultimate insult, and to turn the screws tighter, the Jeffersonian Antifederalists republished the entire pamphlet at their own expense.

Callender attacked Hamilton’s story as soon as it was published, but Hamilton ignored him and so did everyone else. Callender was an obnoxious and personally unclean person who had a history of making wild partisan charges against many officials. His first expose of Hamilton was the high point of his career. He also turned on and attacked his mentor, Thomas Jefferson, but was unable to destroy him. He died soon afterward by drowning while in a drunken stupor.

The Reynolds affair not only ruined Hamilton’s social standing, it destroyed his political future. He had been a serious contender for more important offices including being Washington’s successor, but that future was gone. However, George Washington’s opinion of Hamilton never wavered. He still held him in “very high esteem” and still viewed him as the dominant force in establishing federal law and government.

Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr on 11 July 1804. Ironically, Burr had intervened to avert a duel between Hamilton and Monroe. Burr also represented Maria Reynolds when she divorced her husband and married Clingman.

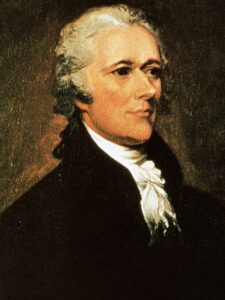

Alexander Hamilton was a Founding Father of the United States. He served in the Revolutionary War, and at 20 years old, became an aide-de-camp to General George Washington and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. He also lead a critical attack against the British at Yorktown.

Hamilton became a leading and powerful American statesman and was an influential interpreter of the Constitution. He was the first Secretary of the Treasury. He established the Bank of North America, the first Bank of the United States, a system of tariffs, and friendly trade with Britain. He was founder of the nation’s financial system, the Federalist Party, the Coast Guard, and the New York Post newspaper.

Honor and reputation were especially important to Hamilton because of his illegitimate birth. He chose to make a complete confession about a moral issue to prove his innocence of the greater sin of corruption and official dishonesty. He was a successful married man who risked everything for clandestine pleasure and was blackmailed. He was the first high-level American government official to have an illicit affair publicly exposed. Many others have suffered the same self-inflicted wound and each one has reacted differently. Hamilton had the dubious honor of being first.

EPILOGUE:

To be complete about this historical incident, I must point out that the story has been told many times. Each author added his own slant and tried to add new facts and fresh analysis, but the basic story has remained intact.

When the affair became publicly known in 1797 there were some who believed it was a cover-up for corruption by Hamilton and his political partners. The Jeffersonian Antifederalists made the absurd charge that Hamilton, John Adams and other Federalists were engaged in a plot to subvert the Republic by reestablishing a king. They lost considerable credibility for making those wild charges. Adams revered the Republic and Hamilton had been investigated by bipartisan congressional committees for fiscal misconduct twice and cleared twice.

The most extensive and credible attack on the credibility of the Reynolds Affair was made by history professor Dr J.P. Boyd. He became suspicious in 1928 because of something he found in the Tench Coke papers (now closed to researchers) and in 1962 he expressed the opinion that the affair should be reexamined because of fresh evidence. Later, Dr Boyd authored a sixty-two-page reexamination.

Boyd believes the affair never happened and was a fiction by Hamilton to cover his corruption in the Treasury Department. Boyd claims Hamilton created the whole story and forged all the papers and letters in the few days before the Muhlenberg, Monroe, and Venable meeting. He also believes that the Reynolds were innocent victims. However, both Reynolds admitted their relationship with Hamilton and Maria provided Hamilton letters to the three congressmen.

Although Dr. Boyd presents a compelling case, I don’t agree with him. I don’t believe anybody could have concocted the story, forged all the letters, provided letters to Maria, and convinced her to turn them over to the congressmen. Too many people were involved, and they all had to tell the right story at the right time. Somebody would have slipped up or have eventually blown the whistle. People have trouble keeping secrets about other people, especially powerful people. In addition, no evidence of corruption by Hamilton has ever surfaced.

If Hamilton was corrupt, he would have had time to plan a way to cover it up without presenting himself as an immoral rake. Boyd also proposed indirectly that Hamilton’s wife was part of the deception, which I believe is doubtful because of the humiliation she had to endure.

There is at least one scholar, Nina Mason, that believes the Reynolds Affair and duel with Aaron Burr were part of a larger conspiracy against Hamilton that was directed by Thomas Jefferson. If true, this would mean that one of our most revered and respected founders organized a plot to lure Hamilton into an illicit affair that involved blackmail, leak the information to expose him, make it appear to others that Hamilton was corrupt forcing him to publicly defend himself, and to cause Burr to antagonize Hamilton into a duel and kill him.

This requires the reader to believe that Thomas Jefferson resorted to trapping his major rival in a web of subterfuge and lies to destroy him and then arrange for his “murder.” Personally, I am not prepared to believe this theory. Jefferson was often outspoken and spiteful and truly believed that Federalism would destroy the very foundation of the Republic. He was not a good man to have as an enemy, but I don’t believe this great man would resort to such excesses to destroy a political foe. I think Jefferson was egoist enough to believe he could destroy any political foe with superior ideas and rhetoric. ilr