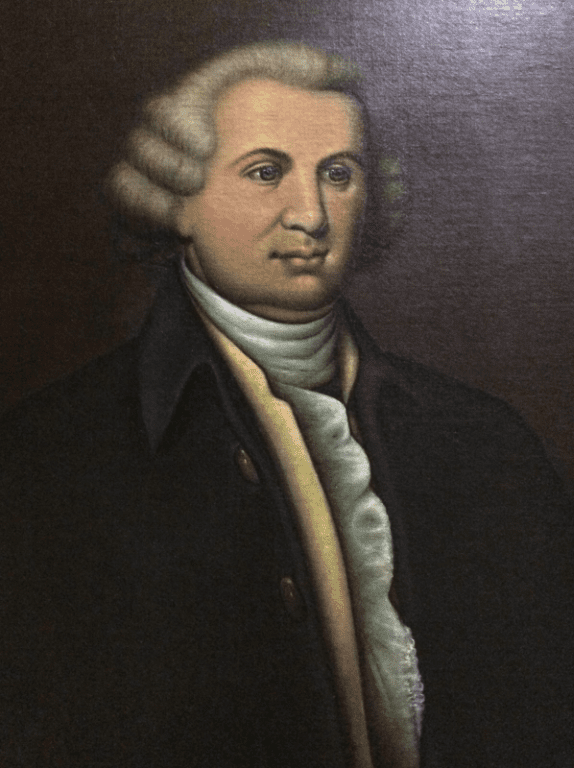

John Penn was a man who overcame a serious lack of early education by intense self-study. He served in the Continental Congress for six years. He signed the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the North Carolina Constitution. He almost single-handedly prepared North Carolina for the British invasion of the south. In 1781 he was summarily relieved of his wartime duties by the envious governor of North Carolina and returned to his law practice. Unfortunately, John Penn’s considerable potential was cut short when he died at the early age of 48.

John Penn was born on 17 May 1741 near Port Royal in Caroline County, Virginia. He was the only son of Moses Penn and Catherine (Taylor) Penn. Moses was a prosperous farmer and modestly wealthy. However, Moses did not see much value in education, so John attended a common school for only two years.

When John was 18 years old, his father died unexpectedly thrusting him into the position of head of the family. The farm required immediate attention and his mother needed care and support. He could run the farm, but he realized that he needed education to do a better job and to reach his personal goals.

John’s uncle, Edmund Pendleton was an accomplished attorney. Thomas Jefferson considered Pendleton to be “the greatest orator” in the colonies and was known for his knowledge and empathy. Jefferson and Adams believed Pendleton’s library had no equal in the colonies. Pendleton took John under his wing and opened his library to him

John Penn spent every spare moment in this library and Pendleton also exposed him to some of Virginia’s finest lawyers. He learned the fine points and techniques of the law, and just three years after his father’s death John Penn was licensed to practice law in Virginia. This was an amazing accomplishment and demonstrated his determination and intelligence.

On 28 July 1763, John Penn married Susanna Lyne, the daughter of Henry Lyne. The couple had three children, but only two survived childhood.

Penn practiced law in Virginia for twelve years during which he distinguished himself as one of the best in Virginia. During this time many of his relatives moved to Granville County, North Carolina so in 1774, he moved his family to the area of Williamsboro, in Granville County.

There appear to have been two major reasons John Penn made the move farther south. One was that he made some “intemperate” remarks about the king and had been reported. He was charged, tried, and convicted, but the judge limited punishment to a one-penny fine. Penn refused to pay, which made him an even bigger target to royal authorities. He was very vocal about his anti-British opinions and refused to be silenced.

The other reason for moving was that he had become convinced that total separation from Britain was the only solution to ever increasingly harsh British rule. Many Virginians, including his uncle Edmund Pendleton, had not reached this conclusion. They still hoped the Crown could be convinced to provide the colonists with the same rights as the residents of Great Britain. They still believed that rights came from government. Penn hesitated to disagree publicly with his uncle who was his benefactor, but he could no longer contain his revolutionary beliefs.

Granville County was the ideal place for Penn because the residents were chaffing under the increasingly harsh British rule and the domination of elite eastern tidewater plantation owners and merchants. They treated the locals like ignorant upstarts and denied them political positions.

Despite the prejudice, Penn rapidly became a leader in Granville County because of his successful law practice and his freely stated views. He was soon elected to the First Continental Congress and to the Provincial Congress. This alarmed the eastern North Carolina establishment who saw him as an intruder and a threat, but they could not contain him.

John Penn emerged as a leader in the Provincial Congress in 1775. He was assigned to important committees, which were to organize a temporary form of government and to prepare a state constitution.

Penn reported to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in late 1775 and declared “My first wish is for America to be free.” He maintained a hectic schedule and in April 1776, he returned to North Carolina to report on actions in Philadelphia.

The Provincial Congress’ “Halifax Resolves” authorized the three North Carolina delegates to support complete independence. This made North Carolina the first colony to officially declare independence from Britain.

The delegation returned to Philadelphia during an unbearably sweltering summer, but congress worked with the windows closed. The delegates were miserable in the heat but there were a few moments of humor. On 1 July, John Dickinson was in the second hour of speaking against independence when the building was rattled by a lightning strike. Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, the oldest delegate, dropped his hickory cane and looked around the room. Penn leaned over Hopkins’ shoulder and explained the lightning had been grounded by Franklin’s lightning rod. Hopkins roared, “I don’t give a damn about any rod or lightning bolt. I’m just tired of Dickinson’s long-winded harangue!”

Also during the summer heat, Henry Laurens, President of Congress, and John Penn had a heated political disagreement that resulted in plans for a duel. The day of the duel the antagonists and their seconds had breakfast together at their hotel. Rain during the night had turned Philadelphia’s unpaved streets into a quagmire. After breakfast Penn and Laurens walked together toward their appointed dueling ground when they came to a crossing deep in mud. Penn acted to help the older man by offering his arm before attempting to cross the street. Because of this act of kindness, they quickly forgot their disagreement, and returned to the hotel without firing a shot.

The North Carolina Continental Congress delegation was composed of William Hooper, a strong Tory; Joseph Hewes who changed with the wind; and John Penn. When the vote on the Declaration was taken on 2 July 1776, Hooper abstained, but, according to Thomas Jefferson, Penn fixed Hewes vote and North Carolina voted for independence. Later all three delegates signed the Declaration of Independence.

North Carolina adopted its Constitution in Dec 1776 and John Penn was a signer. This state constitution officially divided the state government into three branches-executive, legislative and judicial-years before the US Constitution established the same federal organization.

After independence was declared and war was well underway, many congressional delegates, including Penn, had to take on many more duties. These duties included buying military supplies and ordnance, arranging for shipping, and professionally conducting the necessary financial operations. Communications were slow so the delegates were also the main reporters of major events of the day to their constituents. Penn did all these things while religiously attending numerous committee meetings and regular congressional sessions for almost six years.

On 10 July 1778, John Penn was the first North Carolina delegate to vote for and sign the Articles of Confederation. He was one of only 16 men that signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

In July 1779, the Pennsylvania Packet attacked Congress for ineptitude in financial matters and charged that some delegates were using their position to make fortunes on speculations that undermined the continental currency. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts demanded that the publishers be tried for slander and disrespect of Congress.

John Penn rose in defense of freedom of speech. He stated that stopping freedom of speech endangered liberty. He also stated “If you (Congress) have the power, which I doubt, and were to imprison the editor for six months, he would come out a far greater man than when he went in.”

By 1778, the war in the north had reached a stalemate and was a quagmire for the British. France was preparing to enter the war, and King George III was demanding that the British army quickly subdue the colonies. Consequently, the British moved their major operations to the south where they believed they could turn the tide. There were fewer trained Continental troops in the south, and the British believed there was little popular support for the war.

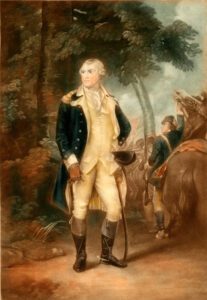

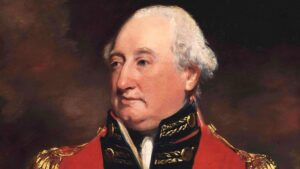

At first it appeared the British were correct in their assessment. They occupied Savannah, Georgia in late 1778 and Charleston, South Carolina in May 1779. They engaged the Americans near Camden, South Carolina on 16 August 1780. The Americans were under the command of Major General Horatio Gates (the hero of Saratoga) and the British were commanded by Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwallis. The American force was unorganized and was mostly untrained militia. The Americans greatly outnumbered the British but the British fielded mostly regulars. The Americans were easily routed and humiliated in the battle.

The Battle of Camden was the worse American defeat of the Revolutionary War. There were pockets of Americans who bravely stood their ground, but the “retreat” was a torrent of desertions and looting. Many soldiers dropped their weapons and ran from the field. According to American Colonel Otto Williams, General Gates, and General Richard Caswell (later governor of North Carolina) were on horseback and ahead of all other deserters. The generals fled non-stop about 60 miles to Charlotte, North Carolina.

In reaction to the Camden defeat, on 23 August, the North Carolina General Assembly appointed Penn to a three-man Board of War to prepare for expected British military operations in that state. Penn took charge when the other two members of the board proved incompetent.

John Penn established effective communications with Major General Nathaniel Greene who had replaced Major General Gates. He raised recruits, found funding for the military, provided transportation and supplies, disarmed Tories, and spurred the people into action.

John Taylor of Caroline described Penn during this period: “He was surrounded by discouraged friends, helpless citizens, or inveterate foes—but he had a task to discharge—and an arduous one. But nature had formed him for the effort. Indefatigable, cheerful, extremely courteous in his manners, firm in his political principles, and invigorated by an inextinguishable ardor, he went through the crisis with honor to himself, to the satisfaction of the state, and rendered service inestimable to the prosecution of the war.”

The British had woefully underestimated the loyalty of the people. The Americans waged a savage guerrilla war that devastated the British and kept them off balance. General Greene was able to pick his conventional battles carefully and by 1781 the tide had turned.

Major Continental victories at King’s Mountain, Cowpens, and General Greene’s standoff with the British at Guilford Courthouse forced Lord Cornwallis to retreat north. His plan was to link up with the British army in the north so they could recover the initiative.

Cornwallis’ plan failed. He was pursued by Greene through North Carolina and Virginia to Yorktown, Virginia on the Chesapeake Bay. Washington moved rapidly south and linked up with Greene and they trapped Cornwallis at Yorktown. The British expected to receive artillery support and reinforcements from the British Navy but the superior French fleet arrived and drove them out of the area.

There was no way that Cornwallis could break the American and French siege, so he surrendered at Yorktown on 19 October 1781. This was the last great land battle of the American War for Independence and led to peace through the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Penn’s outstanding performance during the southern war caused lesser men to be jealous. The most powerful of them was Thomas Burke, Governor of North Carolina, who in 1781 recalled Penn and abolished the Board of War. He did not recognize nor reward Penn for his service and did not offer him another position.

John Penn returned to his wife and home in Stovall, North Carolina in late 1781. He had grown weary in the service of his country but had never wavered in his support of independence. Six years in Congress and his support of General Greene’s campaigns had shattered his physical health and mentally exhausted him.

Penn resumed his law practice for the next few years but died on 14 September 1788. He was buried a few miles northeast of Stovall. On 25 April 1894, his remains were reburied at the Signers Monument at Guilford Courthouse Military Park at Greensboro, North Carolina.

John Penn is not a well-known founder, and I could find no other monuments or memorials other than the signer’s monument on the National Mall in Washington, DC. A World War II US Navy attack transport named after him was sunk by the Japanese in 1943. John Penn contributed much to our Independence, but unfortunately like many other founders is known to few.

The personal sacrifices made by John Penn and other members of the Continental Congress are hard for us to comprehend today. Some traveled more than 700 miles by horseback or stagecoach to reach Philadelphia. The roads were rutted Indian trails that became quagmires when it rained.

Travelers were subject to attacks by renegade Indians and brutal highwaymen. There were few taverns along the roads and the food was terrible. Patrons slept on the floor, ten or more to a room, with the possibility that in the morning you would be missing your boots, purse, pants, or baggage.

John Penn received no salary, only an occasional small voucher for travel reimbursement. It took him more than two weeks to travel about 350 miles from Granville County to Philadelphia.