The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal society with 13 constituent societies in the United States and one in France. It is the oldest patriotic hereditary society in America. It was founded in 1783 by American and French military officers to perpetuate the principles of the American Revolution and to preserve the fraternity between Continental officers. Now in its third century, the Society promotes public interest in the Revolution through its library, museum, publications, and public patriotic activities.

Like many Americans I had heard of the Society of the Cincinnati but knew absolutely nothing about it. I actually thought it had something to do with the Ohio city. Research for this article was a real eye opener for me. The Society has an interesting history, has endured for 238 years, is a bastion of patriotism, and its past and present membership includes many giants of American history.

The Society of the Cincinnati is named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus who left his farm to accept a term as Roman Consul and served as “Magister Populi.” He became the legal dictator of Rome to meet a war emergency, but when the war was won, he willingly chose to relinquish power and returned to his farm. The Cincinnatus story was well known in eighteenth century America. The original concept of public service in America was based on Cincinnatus – that men would leave their careers to serve for a brief time, and then return to their careers. The founders did not envision career politicians.

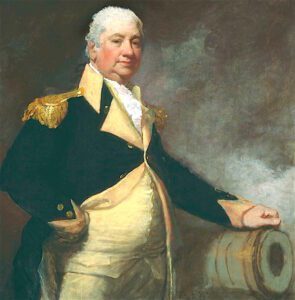

Henry Knox, who became the distinguished commander of Washington’s artillery, originally proposed a fraternal organization of Continental officers in 1775 when the Revolutionary War had just started. He returned to his idea in 1783 when the War had been won and the army was preparing to disband. The War had lasted eight long years and tens of thousands of men and several thousand commissioned officers had served in the Continental forces.

Most Continental officers were young and had risked their lives and sacrificed their private lives to secure independence for the country. They had fought together, and many had died. They had formed the intense personal bonds that are developed during shared combat, and they correctly believed these emotional bonds would last a lifetime. They were proud of their service and that they and their French allies had defeated one of the greatest powers of the eighteenth century. Their bravery and sacrifice had made it possible to establish the first great republic since the fall of the Roman Republic nearly two thousand years before.

The Continental veterans would, however, take home little more than their honor and pride. Congress had promised to pay them half-wages for life, but Congress had not even adequately supplied the military during the war. Most had not received any pay for many months if ever, and they had little confidence in Congress. They were concerned that having won the war, Congress would lose the peace. They were going home to face the problems of once again supporting their families, but with no pay or other help from the nation that had been established by their sacrifices.

The military was the only truly “national” organization in America, and its disbanding would weaken the fledgling government by reducing this binding force. Peace often results in “forgetting” the sacrifices of the conflict. Major General Knox recognized all the problems and wanted to do something positive to improve the situation.

Major General Knox drafted the society’s founding charter (known as the “Institution”) in April 1783 and discussed it with several other officers including his aide Captain Samuel Shaw, Major General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, and Brigadier General Jedediah Huntington. These officers supported the concept, and proposed the organization be named the Society of the Cincinnati. The Institution was formally adopted on 13 May 1783 and signed in June. Copies were sent to the Continental Line of each state to encourage officers to organize state societies.

The Institution outlines the purposes of the organization. I am highlighting the four most important.

The first was to perpetuate the memory of the War for Independence. They realized Americans had to remain vigilant to defend and preserve the liberties, which had been won by the sacrifices made during the War. The founding members were keenly aware that the road ahead would not be easy. The early nation was weak and not completely united, and they knew that freedom could still be lost. Fortunately, the country gained strength and stability. Keeping alive the memory of the War for Independence remains the Society’s most important public purpose.

The second purpose was to maintain the fraternal bonds formed during the War by giving officers a reason to gather in their home states and to have a national meeting every three years. Later hereditary successors had not shared the experiences of the “bloody conflict” but maintained close relationships by remembering the sacrifices of their forefathers and by association with older members.

The third purpose was charitable (“benevolent” in the language of the eighteenth century). Fraternal attachment required each member to demonstrate “brotherly kindness in all things” including financial support to members in distress and to their widows and orphans in times of need. Despite not being paid themselves, each officer donated one month’s pay to establish this fund which was to be managed by the state societies.

The fourth, but unstated purpose was to advocate for those who had served to secure arrears in pay and the half pay for life that had been promised. By disbanding without securing those benefits showed their faith in eventual justice and acknowledged their belief in the subordination of the military to civilian rule. Most revolutions end up with overt military rule or military controlled rule.

The Society of the Cincinnati founders did not want to merely establish an organization of veteran officers. Instead, they wanted to establish an organization of men distinguished by honorable service in a cause that was honorable. Honor, as exhibited by their revered leader, General George Washington was especially important to the founders of the Society. Honor should still be the most important personal trait that all men should aspire to.

Early America did come close to a military coup because of the unresolved pay issues. During the winter and spring of 1783, the unresolved problem of pay had driven enlisted men to the verge of mutiny. Some officers began to consider how the army could be used to compel congress to be just.

In March dissident officers led by Major John Armstrong, Jr, an aide of Major General Horatio Gates, published placards charging that congress would allow veterans to “grow old in poverty, wretchedness and contempt.” They called a mass meeting to be held on 15 March and hundreds of officers attended. To their surprise, General Washington also appeared and made an impassioned speech.

Washington advised them to be patient, and to resist anyone “who wickedly attempts to open the floodgates of civil discord and deluge our rising empire in blood.” This is when Washington pulled a new pair of reading glasses from his pocket to read a letter. He said, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service to my country.” This touched them all and ended any possibility of a military coup.

General Washington had no part in organizing the Society of the Cincinnati but agreed to serve as its first president general. He served in this position until his death in 1799. On 19 June 1783. Major General Knox was elected secretary general and Major General Alexander McDougall was elected treasurer general. Other offices were left vacant until the Society’s first general meeting scheduled to be held in 1784.

The concept of the Society was widely accepted by Continental officers and all thirteen state societies were organized within five months. The Institution defined broad parameters, but the state societies were given a great deal of autonomy. This was intentional and necessary because the country was large, and communications were slow. This Society was one of the first American institutions to be organized nationally.

Originally, Society membership was limited to officers who had served at least three years in the Continental Army or Navy or had served until the end of the War. French army and navy officers who had served were also included. Officers of the Continental Line who had died during the War could be recorded as members, and their membership would be conveyed to their eldest male heir. Officers of Colonial Militias and Minutemen were not entitled to membership. Within 12 months, 2,150 of the about 5,500 eligible officers had joined the Society.

The French Society was also organized early. French officers that had served in our Revolution were enthusiastic about being honored with Society membership. The French obtained the king’s permission and patronage to organize and held their first meeting in January 1784. From the start, the French Society had a mission to perpetuate the trans-Atlantic fraternity that had built up during the War. They wanted to promote understanding and friendship between France and the United States. This continues to this day as a major purpose of the French Society.

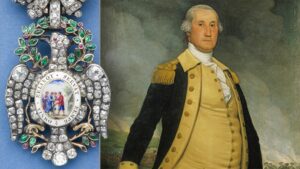

Major General Knox had a provision in the Institution calling for an “Order” (medal) by which “members shall be known and distinguished.” He envisioned a large and complex gold medal to be worn suspended from a neck ribbon. Major Pierre L’Enfant (Continental Army engineer and future designer of Washington DC) persuaded Knox that a badge worn on the lapel would be more appropriate and more practical.

L’Enfant designed an elegant badge consisting of a gold eagle with its wings spread bearing a cartouche on its breast containing an image of Cincinnatus and the Society’s Latin motto (He gave all to serve the republic). Informally known as the “Eagle” it is the most widely recognized symbol of the Society and is highly prized by members. L’Enfant traveled to France in 1784 to have the first group of Eagles made, and to assist in organizing the French Society.

King Louis XVI allowed his officers to wear the Society Eagle. Up until that time they could not wear any foreign medals or decorations.

A diamond encrusted Eagle was given to General Washington by Admiral Comte d’Estaing on 11 May 1784 on behalf of the officers of the French Navy. Upon Wahington’s death in 1799, his family awarded this badge to the next Society President General, Alexander Hamilton. This Eagle has been transferred to each new president ever since. Washington actually had three diamond Eagles and one was presented to Marquis de Lafayette during his grand farewell tour of the United States in 1824. It remained in his family’s possession until 2007 when it was auctioned for 5.3 million US dollars by Lafayette’s great-great granddaughter. It is now displayed in Lafayette’s bedroom at his former home, Chateau La Grange.

News of the formation of the Society was not greeted with overwhelming enthusiasm. The major belief of many was that the Society was an attempt to establish an elite hereditary nobility–the very thing that the Revolutionary War was waged to eliminate. The critics included many well-known and respected Americans, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin.

The debate became very public and even spread to France. Most of the critics concentrated on the charge that the Society was establishing a new nobility that would have too much influence and power. Some feared that they would have the power to elect whoever they favored and consequently control the government which could extend the Society’s control for generations. There was also a fear that the Society could seize power and re-establish a monarchy in America.

George Washington was unaware of the particulars of the charter when he agreed to serve as president general of the Society, and he was having second thoughts. However, L’Enfant returned with the completed Eagles and news of the formation of the French chapter. This made it difficult to abolish the Society. Instead, Washington announced at the first meeting that if the clauses about heredity were not abandoned, he would resign. His demand was accepted, and a new Institution was introduced to eliminate hereditary membership. It was adopted by most of the state societies and the French society.

Once the public furor died down and following the death of Washington, the new charter was rescinded and the original was reintroduced, including the clauses about heredity. The French chapter never reintroduced the document. The last French members were approved on 3 February 1792, shortly before the monarchy was eliminated during their revolution. Many French Society members were killed during the “reign of terror” that followed.

Alexander Hamilton became the second president general of the Society, and the Society began a decade of growth and activity. The Society was well represented in government and the western expansion. However, the Society took no political positions and has remained non-partisan to this day.

The Society suffered a general decline during the early nineteenth century but was temporarily reinvigorated during the 1824-1825 Lafayette farewell tour of the United States and by the fiftieth anniversary of American independence in 1826. The Society took advantage of those commemorations to renew the campaign for the half-pay that Congress had promised Continental officers. Their 45-year-campaign finally paid off in 1828 when Congress granted each surviving officer full pay for the remainder of their lives. By the end of the year only about 850 former officers were collecting the pay. Many had died during the 45 years so Congress got off cheap.

Society membership in 1828 had dwindled to less than three hundred and most were hereditary members. State Societies were beginning to dwindle. By 1844, most of the Revolutionary generation had died, but a 92-year-old veteran of the New York Continental Line (William Popham) was elected president general of the Society. He was the last revolutionary veteran to serve in that position.

Despite suggestions that the Society should disband, Popham stated: “I will never consent to consign to eternal oblivion an institution which received the sanction of Washington.” Popham died in 1847 and was succeeded by Henry A.S. Dearborn, the first hereditary member to serve in that position.

The last surviving Continental officer in the Society, Robert Burnet, Jr from the New York chapter died in1854. That same year Hamilton Fish of New York was elected president general of the Society and they began to take the first serious steps to revive the organization, which had dwindled to six state societies. Fish and other leaders were determined to renew the organization and its national prominence. They were a new generation that wanted all who had served in our War for Independence to be remembered and honored.

The original Institution only admitted descendants of original members as hereditary members. The new “Rule of 1854” allowed the admission of descendants of all qualified officers, even if those officers had not joined the society. This essentially doubled the number of potential members. Five of the surviving six State Societies adopted the new rule. Pennsylvania was the first, but then found their founding documents contained the original Institution and could only be changed by the legislature.

Despite a great start, the revival of the Society was interrupted by the Civil War. Although the State Societies were separated, the common bonds endured and were renewed in 1869 when South Carolina returned to the national convention. By 1872, a southerner was elected to national office and the Society was on the brink of a major renewal and expansion.

The national celebration of the centennial of American Independence prompted interest in Society membership and the reestablishment of the dissolved state societies began. Rhode Island was readmitted in 1877; Connecticut and Virginia in 1896; New Hampshire, Delaware, and North Carolina in 1902; and Georgia in 1904.

The late nineteenth century was a period of steady growth and accomplishment when the Society took the lead in many patriotic commemorations. They sent delegates to the dedication of the Washington monument in 1885. They participated in the 1887 commemoration of the Constitution and in the 1889 commemoration of Washington’s first inauguration. The Society was very involved in the erection of plaques and statues of revolutionary heroes, including the statues of Rochambeau and Lafayette in Washinton’s Lafayette Square. Both were depicted wearing Society Eagles. The Rhode Island and South Carolina Societies located the remains of Major General Nathaniel Greene and moved them to the Greene Monument in Savannah, Georgia.

The largest memorial effort was by the Pennsylvania Society which took the lead in the erection of the monumental equestrian statue of George Washington in Philadelphia. This statue was dedicated by President McKinley in 1897.

The revival of the Society was finally completed when the French Society was readmitted in 1925. This had been discussed in 1881 during the commemoration of the centennial of the victory at Yorktown, Virginia, but was not seriously acted on until World War I. The Society supported American intervention in the war by citing the decisive French support during our War for Independence. The resolution read: “Remembering that it was the aid of France that made the United States a nation, we welcome the opportunity to repay the debt which was then incurred and to help a people whom we love and admire.” The debt was paid in two world wars with a sea of American blood.

Although General of the Army John J. Pershing gave the credit to Colonel Charles Stanton, he allegedly stated: “Lafayette we are here” on 4 July 1917 after American troops arrived in France.

The invigorated Society had long discussed the need for a permanent headquarters and that need was fulfilled in 1938 when Isabel Anderson, acting on the wishes of her late husband, Larz Anderson, gave the Society their elegant and large mansion in Washington, DC. The “Anderson Mansion” has served as Society Headquarters ever since and provides a home for international offices, an extensive library, a museum, and educational programs.

The establishment of a headquarters led to a dramatic increase in membership and to an increase in the Society’s activities and educational programs. In 1937 the Society’s programs had already grown too large and complex to be managed by volunteer members. To compensate they established a non-profit corporation to manage their programs and the Society’s tangible assets. A corporate board drawn from the 14 constituent societies and several committees manage most of the organization’s activities. The Society maintains an extensive and growing library on the revolutionary era and has impressive collections of revolutionary artifacts and art. Researchers and scholars from all over the world use these assets. The Society also conducts public exhibitions, lectures, and symposiums.

Today’s Society is a dynamic organization that is accomplishing the purposes outlined by the founders in the original Institution. They are perpetuating the memory and ideals of the American Revolution and of those who made our Republic possible by their sacrifices.

Most Americans are unaware of the Society and its contribution to the knowledge of our founding because the Society operates without fanfare. I have reviewed a 100-year-listing of Society hereditary and honorary members, and it is impressive. It includes famous military leaders and political leaders, including many US presidents. The membership is a who’s who of people who have contributed much to our national development and security. The Society of the Cincinnati is a 100 percent American patriotic organization. I am happy that I decided to research them. I feel proud that such a group exists to remind us of the sacrifices that have been made to achieve and maintain our freedom. God Bless the USA.