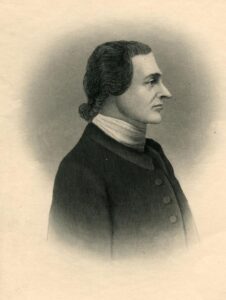

George Taylor’s journey to becoming a founding father differed significantly from others and is one of the more interesting. He imigrated from Ireland in 1736 as an indentured servant to an ironmaster where he learned his lifelong trade. He entered Pennsylvania politics and eventually became a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Of the 56 signers, Taylor was one of only three born in Ireland, the only former indentured servant, and the only tradesman. Sadly, Taylor died before the end of the Revolutionary War and did not witness freedom from England.

NOTE: Indentured Servitude was an economic system that was popular in the early modern period in Europe and North America. In contrast to chattel slavery, indentured servitude required that a worker sell their labor at no wage in exchange for a fixed payment or to fulfil a legal obligation. These indentures had no regulations for working conditions and sometimes led to brutal working conditions. As a result, many servants died before their obligations had been fulfilled. The debt was then transferred to their living family members. While indentured servitude differed from slavery in its terms and social status, it too was a system of unfree labor that sometimes led to the misery and death of its victims.

Little is known of George Taylor’s early life. He is believed to have been born in the north of Ireland about 1716. He was probably the son of a Protestant clergyman. Based on his reading and writing skills it is likely he received a good basic education in Ireland.

Taylor arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1736. To pay for his passage, he had been indentured to Samuel Savage, Jr., who was ironmaster at Coventry Forge northwest of Philadelphia in Chester County. Taylor started as a laborer shoveling coal into the furnace. When it was discovered that he had some education, he was moved to a clerk position.

In 1738, Savage and his mother, Anna Savage Nutt, built a second mill in Chester County, Warwick Furnace. Three years later, Savage died, and the following year Taylor married his widow, Ann. George and Ann had two children, one girl who died early and a son who survived into adulthood.

George Taylor had learned the ironmaking business and became ironmaster, managing both ironworks for the next ten years. During that time, the ironworks grew and prospered, and George and Ann became wealthy. In 1747 George was appointed captain in a Chester County militia group, his first public service.

When Ann’s son, Samuel III, reached legal age in 1752, he became owner of the mills according to the terms of his father’s will. Ann did keep a life right to two farms.

The Taylors continued to live at Warwick Furnace until 1755 when George formed a partnership to lease the Durham Furnace in Upper Bucks County for five years with an option for another five years. They moved into the mansion house on the property. This furnace produced cannon ammunition for the Provincial Pennsylvania Government during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Taylor became active in Upper Bucks County and Durham politics in 1757 when he was commissioned justice of the peace. He was commissioned again in 1761 and 1763.

While still living in Durham, Taylor bought a small stone house in Easton in Northampton County at a 1761 sheriff’s sale. He also acquired a lot across the street where he built a stone stable. The Taylor family moved to this house when the Durham lease expired in 1763 and lived there for about five years. In 1765 they bought a nearby house and sold it to their son, James for 5 shillings and “their natural love and affection.”

Taylor was elected to the Provincial Assembly in 1764 and served until 1769. He was commissioned justice of the peace for Northampton County serving from 1764 to 1772.

In 1767 Taylor purchased 331 acres about 15 miles west of Easton. He built an impressive stone mansion on a bluff overlooking the Lehigh River. This home still stands today. Sadly, George’s wife Ann died in 1768. The location of her grave was not recorded.

Taylor returned to Durham in 1774 having entered into a five-year lease with Joseph Galloway the owner of the ironworks. He leased the ironworks, mines, quarries, forges, and blast furnaces in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The ironworks produced a wide variety of commercial products including Franklin stoves.

In 1775, Taylor negotiated a contract to produce grape shot, cannon balls, bar shot and cannon for the Continental Army. Taylor received little compensation for supporting the war effort and his wealth decreased significantly.

In 1775, following the Battle of Bunker Hill, Taylor was commissioned colonel of the 3rd battalion of militia. This was the county’s first step to prepare for the coming conflict with England.

In October 1775, George Taylor was sent to the Pennsylvania Assembly where he helped draft instructions for the state delegation to the Continental Congress. The instructions were straight forward, do not vote for separation.

Public sentiment hardened against the Crown and the instructions were rescinded in June 1776. Several delegates still refused to vote for Independence, so on 20 July the Assembly chose five replacements: George Taylor, George Ross, George Clymer, Dr. Benjamin Rush, and James Smith.

All five replacements travelled to Philadelphia and signed the Declaration of Independence when it was ready for signatures on 2 August 1776. Of the 56 signers, George Taylor was one of only three born in Ireland, the only former indentured servant, and the only tradesman. He had made quite a social and political climb. He was an early example of achieving the American Dream.

George Taylor was active in the Congress serving on the committee that drew up resolutions calling for the states to raise troops. In January 1777, Congress selected him to arrange and preside at the Indian Treaty Conference in Easton, Pennsylvania. He was elected to the new Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council in March but soon resigned due to illness.

Taylor’s lease of the Durham Ironworks continued through 1779, but the property was seized because the owner, Joseph Galloway, was a Loyalist and traitor who had fled to the British. The authorities tried to evict Taylor, but the Supreme Executive Council allowed him to complete the terms of his lease

The Durham Ironworks was sold in 1779 by the Commissioners of Forfeited Estates. It was purchased by George Taylor, Richard Backhouse, Isaac Sidman, and Robert Hooper Jr. Backhouse took over management of the ironworks, and Taylor moved to New Jersey to lease and run the Greenwich Forge in Warren County.

Taylor moved back to Easton, Pennsylvania in early 1780. He had sold his estate along the Lehigh River and his property in Easton, so he leased a house at Fourth and Ferry Streets.

George Taylor died on 23 February 1781. He did not live to see the end of the Revolutionary War. He was buried in St. John’s Lutheran Church Cemetery across the street from his fourth and Ferry Streets residence. In 1870 the church property was sold to make room for a school and his body was moved to Easton Cemetery.

Local residents had erected an impressive black Italian marble monument in honor of George Taylor in the Easton Cemetery in 1854. In April 1870, his body was moved again and re-buried in front of the monument.

Taylor left half of his estate to his five grandchildren (his son James had died in 1775). The other half was left to the five children he had fathered with his housekeeper, Naomi Smith. He never married Naomi. Unfortunately for the beneficiaries, his estate proved to be insolvent.

George Taylor is not widely known, but he was a patriot. By signing the Declaration of Independence, he risked his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor. He was a hardworking man who started about as low as you possibly could as an indentured servant. He achieved wealth and lived comfortably but when his country called, he answered the call. Serving his country depleted his wealth but he gained the esteem and respect of his contemporaries.

I want to conclude with what an unknown admirer of George Taylor wrote:

“George Taylor was one of the brilliant and forceful men of his time, an earnest and ardent patriot in the trying times of his adopted country’s needs, a fearless and able legislator seasoning every act of his long public career, by hard robust, conservative common sense.”