Education Early America-1607-1860

Education is considered to be the backbone of a nation, which is true, and education has always been tailored to the needs of the time. Recently there was a concentration on the hard sciences and math to meet the need for workers in the fields of space technology and computer development. The subject of education, however, is a bitter battleground, and each group with an axe to grind has an opinion. Some debates on education are fierce and do nothing but further cement opinions and often have little to do with educating our children. This article looks into education during the 17th ,18th, and early 19th centuries to see what did or did not work and to see how education evolved.

Many people currently believe that we should get government out of the schools because government’s intentions can be political rather than educational and by the effect of the different political parties. In contrast, many believe the free market could not get the job done. There is no compromise by these groups, and both refer to “history” as a source of their information.

If you look into history, you will find that for the 200-year period of mid-17th to mid-19th century America, there were few government-controlled schools. By far most educational needs were satisfied by the free market. (In 1860 there were only 300 public schools compared to 6,000 private schools.) During this period, America produced about eight generations of highly skilled and literate men and women. These generations founded and organized a constitutional republic based on freedom and self-government and made it work. They expanded the country, fought and won wars, and the country became a world power.

Our forefathers were educated in a system that included home, church, associations such as library companies and philosophical societies, circulating libraries, apprenticeships, and private study. There was a slight government involvement in some colonies, mostly in New England where the Puritan influence was strong.

Many purchased educational services but during my research on our founders, I have been impressed by how many never received any formal education but were entirely self-educated. These men learned enough to intelligently debate complex subjects, operate businesses, and provide professional services. They could compose complex laws, letters, newspaper articles and pamphlets. They had a remarkable command of both oral and written language.

Early Americans believed that “children are an heritage from the Lord” and parents believed it was their responsibility to teach their children how to make a living and how to live a righteous life. Education usually began with the mother and was continued by the father when the children worked with him.

The mother began teaching the children to read at an early age, but paper was not available to most of the working class. They found alternatives, such as tracing letters in ashes or dust by the fireplace where the mothers did much of their work. They first taught the children the alphabet followed by how to sound out words. A book was then introduced. This was usually the Holy Bible, which was often the only book in the household.

The Bible was a particularly good primer because many passages were familiar to the children having heard them during church and family devotions. The use of the Bible also had the advantage of teaching moral values. The children learned to read early, and if the family could afford it their education was supplemented with other books.

Children often learned basic arithmetic (counting, sums, and times) from their fathers. These men used these basics in their work, such as carpentry, building, and planning for planting and harvest.

Work and “book learning” taught children the value of labor and free enterprise. Idleness was believed to be a sin which would lead to “mischief.” Most families were large, and everybody had their assigned work to support the family. One of the major duties of mothers and other adult females was to educate the younger children and in general they did an outstanding job.

Later, if children were sent to an organized school, they already knew how to read, write, and “cipher.” If they did not go to school, they were educated enough to function as farmers or clerks and to be informed citizens. Many continued by self-education and became traders, merchants, or skilled tradesmen.

The growing demand for more education resulted in grammar and secondary schools being organized, especially in and around the major population centers along the Atlantic seaboard. Most were privately owned but some were chartered by local or colony governments. The government-chartered schools received no government funds but were sustained by private donations and tuition. Religious groups, such as Quakers, Lutherans, and others, also established schools and many of them were dedicated to educating the poor, women, and free blacks.

The education of the young in the south was often fulfilled by “old field” schools. These were school buildings built on unproductive and abandoned farm fields. George Washington received his early education in an old field school.

Those that could afford it hired private schoolmasters to educate their children. This was particularly popular among the planter class in the south. Many educators advertised their services and those that were good prospered while the incompetent were soon weeded out. They offered to teach the subjects that were in demand, such as Latin, Greek, mathematics, surveying, navigation, accounting, bookkeeping, science, English, and foreign languages. Wealthy Americans often sent their sons to England to obtain an education.

The Philadelphia area was particularly endowed with educational opportunities offering 16 fine evening schools in 1767. These schools catered mostly to the German population and concentrated on English and vocations. There were also schools for women and blacks. The large Quaker population was educated in their religious schools, and they often provided free schooling for the poor. Many from other states sent their children to boarding schools in Philadelphia.

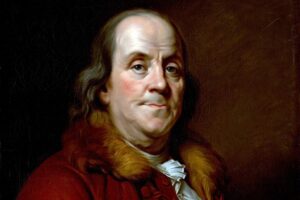

Few early Americans wanted or needed a college education. They were generally unimpressed by degrees because they valued experience and character more. Many of our founders including George Washington, Patrick Henry, and Benjamin Franklin did quite well without a college education. However, for those who wanted it college education was available. Most early college students were pursuing a career in the Christian ministry. Some studied law but most lawyers were self-educated. Colleges mostly offered a “Classical” education.

In England, the government had granted Cambridge and Oxford a monopoly on granting degrees, but in Colonial America there were nine colleges. They were (in order of their founding): New College (Harvard), College of William and Mary, Collegiate School (Yale), College of New Jersey (Princeton), King’s College (Columbia), College of Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania), College of Rhode Island (Brown), Queen’s College (Rutgers), and Dartmouth.

Thomas Jefferson attended William and Mary and the Father of the Constitution, James Madison attended Princeton. The nine early colleges become part of the fabric of the United States and produced an impressive number of the nation’s leaders and educators. Some of these colleges were started by government, but all were sustained and expanded by voluntary contributions.

Libraries supplemented all levels of education, but they also allowed individuals with no schooling to self-educate. Demand resulted in the establishment of many libraries. Unlike those in Europe where libraries were restricted to scholars, churchmen, and government officials, American libraries were mostly open to all. Churches also set up libraries, which were open to their parishioners.

Some libraries were maintained by membership fees, but the fees were often waived if a person showed intellectual promise and character. Public philanthropy made it possible for even the poorest citizens to borrow books.

Colonial American’s desire for self-improvement led entrepreneurs to develop innovative ways to sell and rent all types of printed matter. One was the “circulating library” which was first opened in Philadelphia in 1767. This library was quite successful and new ones popped up throughout the colonies. These were the forerunners of today’s bookmobiles.

Philosophical societies were established throughout the colonies. Some of these groups were made up of men who met to discuss their own writings. Some were discussion groups open to all to discuss any books, articles, and pamphlets. Although limited in numbers these societies and discussion groups were highly effective educational tools.

Church attendance was very high in colonial days (actual membership was much lower since membership was difficult to attain.) Church sermons were often printed, and members of the congregations would meet to study and discuss the sermons. These meetings involved a large part of the population and were an effective learning and religious experience. The sermons were also discussed in the parishioners’ homes.

The foregoing information shows that early Americans were anxious to learn and that there were many paths to achieve an education. The result was that early Americans were highly literate. An 1800 study by DuPont de Nemours showed that only four in a thousand Americans were unable to read and write. Ben Franklin in his autobiography claimed that libraries alone “have improved the general Conversation of Americans, made the common Tradesmen and Farmers as intelligent as most Gentlemen from other Countries, and perhaps have contributed in some Degree to the Stand so generally made throughout the Colonies in Defence of their Priviledges.

There was some early state supported schooling beginning in 1790 when Pennsylvania became the first state to require free education for the poor only. New York followed suit in 1805. In 1820, Massachusetts was the first state to have a tuition-free high school for all, and the first state to require compulsory education. By the late 1800s, public education had spread to most states, in a movement often referred to as the “common school movement.”

Federal involvement began with the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which granted federal lands to new states and set aside a portion of those lands to be used to fund public schools. Serious federal involvement began with the enactment of the Morrill Act. Signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1862, the first Morrill Act began to fund educational institutions by granting federally controlled land to the states for them to sell, to raise funds, to establish and endow “land-grant” colleges. The mission of these institutions as set forth in the act is to focus on the teaching of practical agriculture, science, military science, and engineering—although “without excluding other scientific and classical studies.”

The original Department of Education was created in 1867 to collect information on schools and teaching that would help the States establish effective school systems. In 1980, Congress established the Department of Education as a Cabinet level agency.

Despite the changes previously noted, actual change in education came about slowly. One-roomed schoolhouses were a part of rural America until at least the 1950’s. In Missouri, where I grew up, consolidation of schools came when I was in Junior High School (1949-1951). Not everybody was pleased with the change but eventually learned to live with it.

School included strong doses of patriotism and religious beliefs. Corporal punishment was still the rule rather than the exception. I had my butt burned at least twice a month and one teacher would pound on us with a rolled up magazine. This was all done for our own good and we thrived on it. Our vocational agriculture department had received an unbelievable amount of surplus shop equipment and we also acquired a lot of vocational skills. We learned and I owe those teachers and administrators more than I could ever repay.

Education today seems to be in disarray and in need of serious change, but I am confident that it will all be sorted out and that children will again learn the basics that are the foundation that all else is built on.